Introduction

The way Hollywood operated during its heyday was vastly different than how it currently does. The Studio System was a business structure. One where the production and distribution of films were dominated by a small number of large movie studios.

The largest studios, dubbed “The Big Five,” were Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, Warner Brothers, RKO Radio Pictures, and 20th Century Fox. They dominated the movie business with huge distribution channels and theatre ownership across the country. Universal Pictures, United Artists, and Columbia Pictures were also major studios that instituted the same practices as the Big Five. However, they simply didn’t have the same reach and influence as The Big Five.

In the Golden Age of Hollywood, studios discovered their own stars and signed them to multi-year contracts. A weekly salary could range anywhere from around $200 to over $7,000. For example, Gary Cooper, the highest-paid star of 1937, had an annual salary of $370,214 ($7,119.50 per week). However, Peter Lorre earned just $15,265 ($293.56 per week) that same year.

While under contract, the studios controlled nearly every aspect of the lives of the stars that appeared in their films. In this article, we will discuss the myriad of ways this occurred. We’ll also provide examples of stars directly impacted along the way.

Fit and Finish

There’s an old expression in Hollywood when adapting an existing work for the Silver Screen: “What can we change?” When creating a new star under the Studio System the major studios applied this same logic to their would-be stars.

Rita Cansino was a promising dancer and actress when she signed with Columbia Pictures to a seven-year contract in 1936. Studio Head Harry Cohn decided her look and name were too Spanish to be truly marketable. Subsequently, her name was changed to Rita Hayworth. She also underwent plastic surgery to Anglicize her nose. Finally, she was given electrolysis treatments to “fix” her hairline.

Many other stars throughout the era also had similar experiences as Hayworth. This included Norma Jean Baker, who would become Marilyn Monroe after extensive facial plastic surgery to her nose and chin.

Like many executives in Hollywood, Cohn expected aspiring actresses to have sex with him in exchange for a chance at stardom. Cohn kept shelves of perfume and stockings in his office, which he would offer young women as payment for sexual favors. Most women gave in to him, but stars such as Joan Crawford, Rita Hayworth, and Kim Novak never did.

“Harry Cohn thought of me as one of the people he could exploit, and make a lot of money. And I did make a lot of money for him, but not much for me.”

– Rita Hayworth

Other ways studios transformed their stars were via acting and voice lessons. Actress Lauren Bacall was given the latter when she first signed on with Warner Brothers. These lessons were what developed the actress’s signature voice, which set her apart from the other female performers of her day.

Movie Roles

During Hollywood’s Golden Age, movie stars had little to no say about which roles they accepted. They were essentially locked into movies produced by the studio. For example, under their contract with Paramount Pictures, which lasted from 1929 to 1933, the Marx Brothers only appeared in movies made by that studio. However, there were instances where the studios would loan out their stars to other studios. These contracts between the studios would cover everything from start dates, to salary, as well as star billing and publicity.

Possibly the most famous example of this is when Clark Gable was loaned out by MGM to Selznick International Pictures to play Rhett Butler in Gone With the Wind (1939). In this particular example, Gable earned $4,500 per week while filming the movie and was on loan to Selznick as soon as he completed filming on Idiot’s Delight (1939) for MGM.

Screen legend Bette Davis attempted to test the system while at Warner Brothers and refused roles she wasn’t interested in, including Mildred Pierce (1945). This rebellion caused Warner Brothers to suspend Davis for her defiance and refusal to follow the rules.

Columbia star Rita Hayworth was similarly suspended for nine weeks for refusing to appear in Once Upon A Time (1944). This was because the plot revolved around a dancing caterpillar named Curley and she found it absurd. In 1952, she was suspended again by Columbia for failure to show up to shoot Affair in Trinidad.

“I was in Switzerland when they sent me the script for Affair in Trinidad and I threw it across the room. But I did the picture, and Pal Joey, too. I came back to Columbia because I wanted to work and…I had to finish that goddamn contract, which is how Harry Cohn owned me!”

– Rita Hayworth

Image Rules and Publicity

Studios were very concerned with the image of their stars, especially women. As a result, they did everything in their power to create and control how their stars were portrayed, both on and off the screen.

It was not uncommon for contracts for actresses to have mandatory weight limits written into their contracts. Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich were both told to lose weight when they first arrived in Hollywood. Strict diets were often implemented to help stars lose weight including broth, cottage cheese, and toast.

“I am not ashamed of being a woman. I intend to keep on looking like one. Trousers on women are quite hideous. You will never – I repeat – never see a woman wearing trousers on Park Avenue!”

– Adrienne Ames

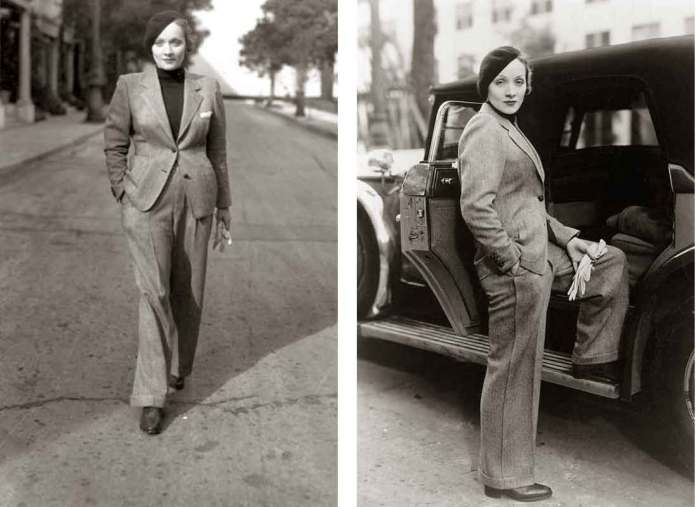

It was strongly prohibited for women to wear pants. In 1932, Marlene Dietrich caused an uproar in Hollywood when she began to wear pants instead of dresses. Katherine Hepburn, also a fan of pants, had hers confiscated for not meeting RKO studio guidelines. When this occurred, Hepburn walked around the set in her underwear.

“I have never seen a single woman who looked well in trousers. I adore men’s tailoring – but trousers? No!”

– Carole Lombard

Stars always needed to be ready for the cameras as promoting them in the press was highly desired. One of the ways stars were promoted by the studios was to have them go on “sham dates” with each other to drum up press for a movie. An example of this was Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney pretending to be a couple while promoting the movie Babes in Arms (1939).

Marriage and Children

The studio also put their fingerprints on the marriages of their stars. When William Powell wanted to marry Jean Harlow in 1935 the union was stopped by MGM. This was due to a clause written in Harlow’s contract which prohibited her from marrying because a married woman couldn’t be a sex symbol. On the flip side, when Elizabeth Taylor married her first husband, Nicky Hilton, MGM used her wedding to promote her movie Father of the Bride (1950).

Actress Judy Garland went against MGM, marrying composer David Rose with whom the studio did not approve. As punishment for going against the studio, she was required to report to work the day after the wedding forcing the couple to cancel their honeymoon plans.

Many actresses had strict rules which prohibited them from giving birth written into their contracts. Ava Gardner terminated two pregnancies while married to Frank Sinatra, unbeknownst to him. Other stars that had abortions due to contractual obligations include Judy Garland, Jean Harlow, Marilyn Monroe, and Fay Wray.

Female stars found ways to become mothers while working in the Studio System. This was done primarily by adoption. Actress Loretta Young became pregnant from a sexual encounter with Clark Gable while shooting The Call of the Wild (1935). Young, a devout Catholic who was strongly opposed to abortion, collaborated with her mother and sisters to come up with a plan to keep the baby. The actress traveled to England for a “vacation” and returned right before she gave birth on November 6, 1935. A few weeks later the baby, Judith, was placed in an orphanage with Young adopting her own child nineteen months later.

The Rules For Child Actors

Child actors arguably had it harder than anybody else. Without the child labor laws in place that exist today, children were exploited and forced to work long hours as if they were an adult. For example, Judy Garland would typically be expected to work six days a week for eighteen hours a day. To keep her working, MGM gave her a cocktail of “pep” pills and then countered them with sleeping pills when she was not working. This led to a lifelong battle of addiction for the actress.

“Time is money. Wasted time means wasted money means trouble.”

– Shirly Temple

The End of the Studio System

On May 3, 1948, a federal antitrust suit, United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., was decided by the United States Supreme Court. The case pertained to the ability of a studio to own its own theater chains. The landmark decision went against the studios 7-1.

By 1957, the Studio System was nearing its end with more and more stars becoming freelancers. This was because the risks of making a mediocre picture were much greater without the studios controlling the theatrical chains.

“We find ourselves in a highly competitive market for these talents (stars, directors, producers, writers). Under today’s tax structures, salary to those we are dealing with is less inviting than the opportunity for capital gains. We find ourselves, therefore, dealing with corporations rather than with individuals. We find ourselves, too, forced to deal in terms of a percentage of the film’s profits, rather than in a guaranteed salary as in the past. This is most notable among the top stars.”

– Harry Cohn in the Columbia Pictures Annual Report from 1957

By the 1960s, the movie studios were in major financial trouble due to many movies not being profitable. They turned to the reissue of older films theatrically and on television. By the decade’s end, Hollywood was in a major recession. The 1970s would eventually usher in a new age of financial success for Hollywood with blockbusters such as The Godfather (1972), Jaws (1975), and Star Wars (1977) leading the charge.