Dancer. Movie Star. Mistress. Actress. Author. Vamp. Vixen. Victim. Lulu. Legend. Louise Brooks was all of these things and more.

“The great art of films does not consist of descriptive movement of face and body, but in the movements of thought and soul transmitted in a kind of intense isolation.”

– Louise Brooks

Early Life

Mary Louise Brooks was born on November 14, 1906, in Cherryvale Kansas, a quaint little town that hit its peak population in 1920, with a total of 4,698 people. Her father, Leonard, was an accomplished attorney. Her mother Myra was an artistic bohemian who was more interested in art and music than in raising children.

Brooks and her three siblings led fairly carefree lives, which included friendships with neighborhood children. One of these children, Vivian Jones, would grow up to be Vivian Vance of I Love Lucy fame.

At the age of nine, Brooks’ life would forever be altered when she was sexually assaulted by an adult neighbor. She kept this secret for many years. When she finally told her mother about it, the young girl was told it was her fault for leading him on. This had serious psychological implications for her concerning sex. She would reflect decades later:

“(The sexual assault) must have had a great deal to do with forming my attitude toward sexual pleasure….For me, nice, soft, easy men were never enough. there had to be an element of domination.”

Dancing Career

In 1922, at the age of fifteen, Brooks was invited to join the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts. The school, with branches in Los Angeles and New York City, was designed to produce professional dancers to perform in the school’s professional dance company.

For the next two years, Brooks traveled as part of the company, spending time in both London and Paris. She eventually was given a starring role opposite modern dance pioneer Ted Shawn. Shawn co-owned the school with his wife Ruth St. Denis, who grew to despise Brooks and her carefree lifestyle.

The hatred St. Denis felt for Brooks reached a fever pitch in 1924 when she abruptly fired her in front of the rest of the troupe by saying:

“I am dismissing you from the company because you want life handed to you on a silver salver.”

She was just 17 years old.

Brooks was not unemployed for long. She hit up her close friend Barbara Bennett (sister of Joan and Constance) who got her a job as a chorus girl in the Broadway smash George’s White Sandals. The following year she danced as part of the Ziegfield Follies in a semi-nude role.

Paramount Pictures

“I was always late, but just too damn stunning for them to fire me.”

– Louise Brooks

One evening, Walter Wanger, a movie producer with Paramount Pictures, attended a Ziegfield Follies performance and became immediately infatuated with Brooks. He quickly signed her to make movies with the studio. Brooks and Wanger began an affair that would last years but would be sporadic.

It wasn’t long before Brooks caught the attention of another powerful man in the picture business, Charlie Chaplin. They met at a cocktail party thrown by Wanger for the premiere of The Gold Rush and began an affair that lasted two months (Chaplin’s 16-year-old wife Lita Grey had just given birth to their son Charles Chaplin Jr. a month before the affairs’ beginning). Chaplin ended the affair by sending Brooks a check.

“I was eighteen in 1925, when Chaplin came to New York for the opening of The Gold Rush. He was just twice my age, and I had an affair with him for two happy summer months. Ever since he died, my mind has gone back fifty years, trying to define that lovely being from another world.”

– Louise Brooks

In 1925, Brooks regretted the decision to participate in a nude photoshoot two years earlier. She sued the photographer, John de Mirjian, in an injunction lawsuit to prevent the pictures from being released.

Brooks’ early pictures had her in bit roles. Her first movie was The Street of Forgotten Men (1925), which was uncredited. She followed this up with The American Venus (1926), which is now lost.

“I have a gift for enraging people, but if I ever bore you it will be with a knife.”

– Louise Brooks

Around this time, Brooks was offered a contract with MGM, which Wanger urged her to accept to squash rumors that she only got her roles at Paramount due to their affair. Instead, Brooks signed a contract with Paramount.

Starring Roles

Her first starring role was in another lost film, A Social Celebrity (1926) opposite Adolphe Menjou (A Woman of Paris). The plot of this comedy revolves around a barber who pretends to be a French Count in New York City. Brooks played a showgirl that used to work as a manicurist at the barbershop, owned by the main character’s father.

She followed up that film with It’s the Old Army Game (1926) with W.C. Fields (Poppy). The title of the movie refers to a shell game that is observed by Fields’ character. The movie’s director, Eddie Sutherland, and Brooks were married shortly after production on the film was completed.

Brooks didn’t take to married life, and soon began an abusive affair with laundromat magnate George Preston Marshall in 1927. She would divorce Sutherland in June 1928 and her now ex-husband would attempt suicide via sleeping pills the night the divorce papers were finalized. Brooks and Marshall would participate in this on-again-off-again relationship from 1927 through 1933.

Beggars of Life (1928) was filmed while Brooks was still married to Sutherland. Widely considered Brooks’ best American movie, it was notable for also being the first movie made by Paramount to feature scenes with sound (these scenes are now lost). Director William Wellman invented the boom microphone for use in this movie.

“Most beautiful dumb girls think they are smart and get away with it, because other people, on the whole, aren’t much smarter.”

– Louise Brooks

One night while on location in San Diego County’s Jacumba Mountains, Brooks clashed with Wellman over his insistence that she perform dangerous stunts in the movie herself. A sequence where she had to board a moving train was so hazardous she could have been killed with a single misstep.

Scandal

Around this time Brooks began to rub elbows with the rich and famous in the bi-coastal social scene, most notably William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies. On one visit to San Simeon, while The Great Canary Murder Case (1929) was in production, she began a sexual liaison with Davies’ niece, actress Pepi Lederer. In 1935, Lederer was committed to a mental institution under the direction of Hearst due to her lesbian liaisons. She would commit suicide shortly after being committed to the institution by jumping out of a window. Lederer’s death upset Brooks greatly and would haunt her for the rest of her life.

“When I am dead, I believe that film writers will fasten on the story that I am a lesbian…I have done lots to make it believable…All my women friends have been lesbians…There is no such thing as bisexuality. Ordinary people, although they may accommodate themselves, for reasons of whoring or marriage, are one-sexed. Out of curiosity, I had two affairs with girls — they did nothing for me.”

– Louise Brooks

Around this time Paramount reneged on a promised weekly raise in Brooks’ pay. Weary of Hollywood, and feeling low in spirits, Brooks quit Paramount Pictures the day filming was completed on The Great Canary Murder Case. Subsequently, she headed with Marshall to Germany to star in Pandora’s Box (1929).

European Movies

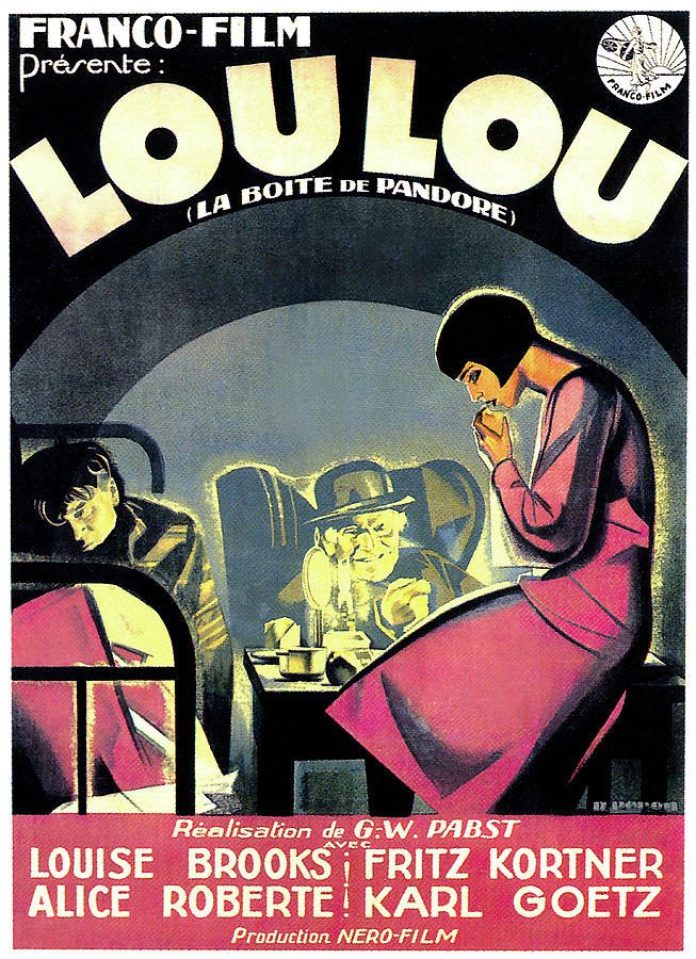

When acclaimed German director G.W. Pabst saw Louise Brooks in A Girl in Every Port (1928) he knew he wanted her to portray Lulu. She is the seductive and carefree girl who brings ruin wherever she goes. Pabst’s new version of Pandora’s Box was a popular story with German audiences at the time. However, she was still filming The Great Canary Murder Case and Paramount didn’t want to loan her out after the movie had wrapped.

On her way out the door from Paramount, the actress was told of Pabst’s offer for her to star in Pandora’s Box. In return, Brooks had asked the studio to wire Pabst a message stating that she would indeed accept the role.

Pabst’s second choice, Marlene Dietrich, was actually in his office about to sign the paperwork for the role, when he got the message from Hollywood that Brooks was in. Fate had intervened at the last possible second, and Brooks had secured the role that would define her for all time.

“I’d never heard of Mr. Pabst when he offered me the part (in Pandora’s Box). It was George who insisted that I should accept it. He was passionately fond of the theater and films, and he slept with every pretty show-business girl he could find, including all my best friends. George took me to Berlin with his English valet.”

– Louise Brooks

When Brooks finally arrived in Berlin things got off to a rocky start. After shooting ceased every day, she would go out partying and getting drunk every night with Marshall and coming to the set exhausted and hungover. This caused friction between her and her co-star Fritz Kortner.

“Kortner, like everybody else on the production, thought I had cast some blinding spell over Pabst that allowed me to walk through my part… Kortner hated me. After each scene with me, he would pound off the set to his dressing room.”

– Louise Brooks

Pabst used the growing animosity and friction between Brooks and the other cast members to coax subtle, naturalistic performances out of the performers that enhanced each scene. Other things Pabst did that were unorthodox included hiring tango musicians to play between takes, as well as limiting Brooks to a single emotion per shot.

Lulu

When Pandora’s Box was released in theatres it was hated by audiences in both Germany and the United States, especially Brooks’ performance. The Germans hated her because she wasn’t a German, believing only a German should play the part of Lulu.

Americans hated her naturalistic performance, which went against the exaggerated performances that silent audiences had expected. Nevertheless, the movie went on to make Brooks an international star.

“In Hollywood, I was a pretty flibbertigibbet whose charm for the executive department decreased with every increase in my fan mail. In Berlin I stepped to the station platform to meet Mr. Pabst and became an actress. And his attitude was the pattern for all. Nobody offered me humorous or instructive comments on my acting. Everywhere I was treated with a kind of decency and respect unknown to me in Hollywood. It was just as if Mr. Pabst had sat in on my whole life and career and knew exactly where I needed assurance and protection.”

– Louise Brooks

Brooks worked with Pasbt again in Diary of a Lost Girl (1929), where Brooks plays a young woman, Thymian Henning, who is raped. Brooks used memories of her sexual abuse at the age of nine to feed her performance in this now-classic film.

“Louise has a European soul. You can’t get away from it. When she described Hollywood to me—I have never been there—I cry out against the absurd fate that ever put her there at all. She belongs to Europe and to Europeans. She has been a sensational hit in her German pictures. I do not have her play silly little cuties. She plays real women, and plays them marvelously.”

– G.W. Pabst

Her last European movie was Miss Europe (1930), a French film directed by Italy’s Augusto Genina, which Pabst produced. This was the first sound movie to star Brooks. However, all of her dialogue and singing were dubbed later.

Last Movies

Brooks returned to New York City and Marshall in 1929. It would be two years before she traveled back across the country and returned to Hollywood. Despite being essentially blacklisted due to her abrupt departure from Paramount she was cast in two movies It Pays to Advertise starring Carole Lombard (To Be or Not to Be) and God’s Gift to Women with Joan Blondell (Three on A Match). Both of these roles were fairly small.

“When I got back to New York after finishing Pandora’s Box, Paramount’s New York office called to order me to get on the train at once for Hollywood. They were making The Canary Murder Case into a talkie and needed me for retakes…I said I wouldn’t go…In the end, after they were finally convinced that nothing would induce me to do the retakes, I signed a release (gratis) for all my pictures, and they dubbed in Margaret Livingston’s voice…Goaded to fury, Paramount planted in the columns a petty but damaging little story to the effect that it had been compelled to replace Brooks because her voice was unusable in talkies.”

– Louise Brooks

William Wellman, who directed Brooks in Beggars of Life offered her the lead female role in The Public Enemy (1931), which she promptly turned down so she could return to Marshall in New York City. Turning down this role, which went to Jean Harlow (Bombshell) would be the fatal blow to her movie career.

Brooks was given an offer by Columbia for $500 per week (approximately $8,900 adjusted for inflation) but refused to do a screentest, and the offer was withdrawn. She appeared in a two-reel comedy short Windy Riley Goes Hollywood (1931) directed by Fatty Arbuckle under the name “William Goodrich.”

After that short, she would only star in a couple more pictures in her life: Empty Saddles (1936) and Overland Stage Rangers (1938), where she played opposite John Wayne (True Grit). She would also appear as a glorified extra in the movie When You’re In Love (1937).

Dark Years After Hollywood

In the 5 years between Windy Riley Goes Hollywood and Empty Saddles, several important things happened to Brooks. In 1932 she declared bankruptcy and had to make ends meet by dancing in nightclubs. Around this time Marshall ended the relationship he had with Brooks and married actress Connie Griffith (The Divine Lady).

Brooks then married millionaire, William Deering Davis. She left him five months later, and they were officially divorced in 1938. By 1940, Brooks was broke and working as a copywriter for a salary of $55 per week.

Although the former actress was now out of the movie business, Brooks was still close with Walter Wanger. The producer told her that she would eventually become a call girl if she continued to live in Hollywood.

Heeding Wanger’s words, Brooks packed her suitcase and headed back home to Kansas, where she opened a dance studio.

“I retired first to my father’s home in Wichita but there I found that the citizens could not decide whether they despised me for having once been a success away from home or for now being a failure in their midst.”

– Louise Brooks

Louise Brooks eventually headed back to New York City and ended up working at the retail store Saks Fifth Avenue as a salesgirl. In 1948 her financial situation had worsened. Brooks had subsequently turned to alcohol and contemplated suicide. The former actress embarked on the seemingly destined career as a call girl. She also began to write her autobiography during this time, but in a fit of drunken anger, she tossed the draft into a furnace, destroying it.

Brooks continued to do this for five years until she eventually began to turn her life around. She has gone on record as stating that her conversion to Catholicism was the foundation for this change in her life.

Later Years and Legacy

Around this time a new generation of audiences was discovering her movies. These new fans loved her performances. Subsequently, a film festival of her movies was held in 1957 in Rochester, New York, where Brooks now resided. She had moved there a year earlier to work as a writer of cinematic essays for the George Eastman House.

For the rest of her life, Brooks gave interviews about her films to various documentarians. She also would write essays about film as well as about her life. In 1982, a collection of her writings was published, Lulu in Hollywood.

Brooks suffered a heart attack in 1985 and passed away. She was 78 years old. Her performance in Pandora’s Box is now widely considered to be one of the greatest in the history of the silent film era.