Introduction

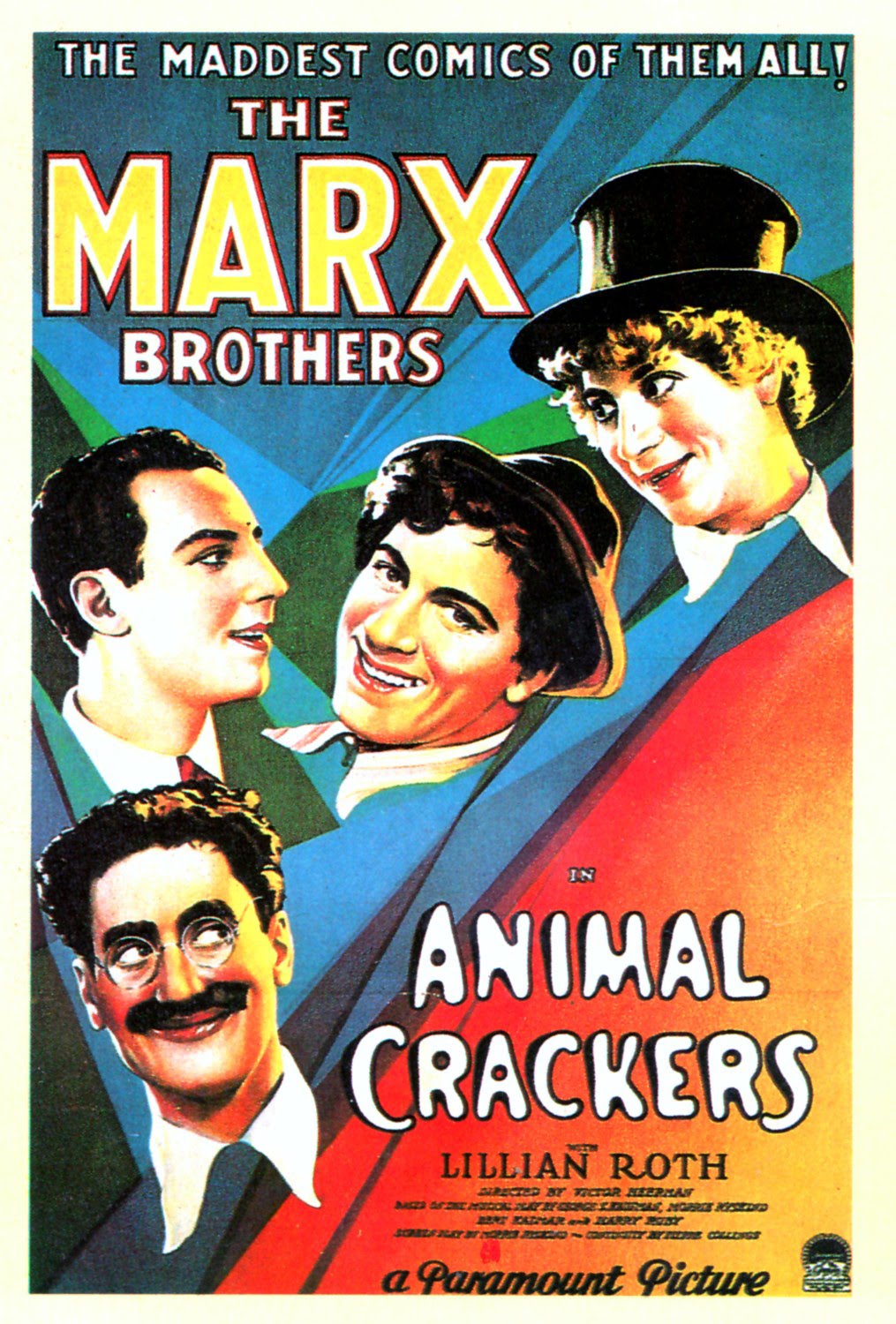

Comedic musicals often have a compelling underlying theme driving the singalong whimsy. The film version of the Marx Brothers.’ crooning-and-laughing stage spectacle Animal Crackers (1930) presents a bold thematic question, “What’s wrong with a little dishonesty if it helps a harmless make-a-buck angle?”

The dishonesty plays out when several con artists enact dueling schemes to steal an exquisite painting with no intention of keeping it. Everyone wants to replace it with a forgery, stating they’ll put the original back soon enough. The plan does sound “crackers” until audiences discover the motivation. Dishonesty’s purpose here involves making an honest living. Yes, something really crackers is going on at a Long Island estate.

The Story

Mrs. Rittenhouse, the estate matriarch and the only honest person in the feature, suffers more than an indignity when a rare Beaugard painting goes missing. She becomes responsible for “After the Hunt’s” $100,000 price tag.

Perhaps Mrs. Rittenhouse can rely on the assistance and antics of legendary hunter, explorer, and ne’er do well, Captain Spaulding, played by Groucho Marx. Maybe the double spelling of “Jeffrey” and “Geoffrey” Spaulding isn’t a “crazy credits” flub. The Captain himself could be mixing up a made-up name to complement his made-up claims of adventures. Spaulding is not one for details.

The guest of honor’s boasts lacks truthfulness and clarity. Spaulding’s tale of shooting a polar bear would be credible if he didn’t mention he killed the bear in Africa. When challenged, the Captain replies:

“…He was a rich bear who could afford to go away in the winter…”

The Absurdity

Spaulding is a notorious phony and blowhard, but he’s funny and gets a pass. Actually, he’s almost overshadowed in the phoniness department by some other visitors throughout Animal Crackers. They get a pass for humor, too.

Is there anything more absurd than taking Harpo Marx’s looney, childlike character as a learned musical professor? Guests look the other way at his over-the-top silly behavior, assuming eccentricities and classically trained musicianship go hand-in-hand. No one guessed the Professor conned them to get a party booking and accompanying free meal.

At least Chico Marx’s lounge-act musician “Ravelli’s” character remains honest in his flagrant displays of dishonesty. His (talented) musical act also serves as a cover for running con game money schemes.

Dishonest fun, however, seems preferable to honest, downright meanness. Not everyone is so disingenuously genuine with (mainly) harmless scam intentions. For some, pulling a cruel prank underscores their actions. Grace Carpenter and her friend Mrs. Whitehead intend to steal and switch the painting with a laughable forgery to embarrass the kind and decent Mrs. Rittenhouse. Why? No reason outside of curious animosity and jealousy.

The Mystery

There’s a mystery to solve when the painting goes missing, or else so goes Mrs. Rittenhouse’s reputation and fortune. Spaulding comes to the (self-serving) rescue, hoping to solve the mystery and find the painting. Recovering the painting allows the overstating guest of honor to show he’s more than all talk. Of course, Spaulding’s detective skills are all bluff.

Spaulding gets some much-needed and mostly ineffective assistance from Ravelli and The Professor, who helped with the theft! Spaulding states “What would motivate someone to steal a painting?” Ravelli responds “Robbery.” True, but in Animal Crackers, we’re only getting part of this complex and ridiculous story.

Young Arabella Rittenhouse, Mrs. Rittenhouse’s niece, wants to continue her life as a socialite. However, she loves destitute John Parker, a talented artist whose abilities no one recognizes. Arabella devises a scheme to help John out, ie. steal “After the Hunt” and replace it with John’s imitation.

An imitation that is better than Beaugard’s original. Arabella sees the steal-and-switch plan as a way to get John much-needed attention and a thriving art career. John’s version of “After the Hunt” is remarkably better than Grace’s poor art school duplicate, but Grace wants her awful painting unveiled to ruin Mrs. Rittenhouse. Maybe there’s a history here where Mrs. Rittenhouse wouldn’t display Grace’s artwork?

Motivations

Motivations in Animal Crackers may vary wildly, however, both connivers know who to turn to for the dirty work of stealing. Further, dueling stealing takes place when both bait and switch schemes take place simultaneously. It’s not that hard to run such schemes. Helping hands abound.

At one point in Animal Crackers, Ravelli states “You want I should steal?” Grace responds “Oh no, no, it’s not stealing.” Ravelli, with certainty, states “Well, then I couldn’t do it.” Lying and stealing do take place aplenty. Yet, audiences don’t feel equally repulsed at everyone’s equally distributed dishonesty. Perhaps they took a page from a Marx Brothers’ contemporary Moe Howard. In the conquering Stooges’ words:

“If you’re going to cheat, cheat fair! If there’s anything I hate, it’s a crooked crook!”

Further, what is the essence of crooked, and what makes a crook crooked? Stealing is still stealing. Removing an artwork from the Louvre, keeping it for only a day or two, and returning it (folded!) would doubtlessly garner swift forgiveness. Usually, audiences won’t give unlikeable actors performing dishonest acts a pass without a reason. Identification might be at work here.

Forgiveness

1930 represented the uncertain sophomore year of the Great Depression. Troubled citizens needed to do what they could to get by, leading audiences to forgive untoward behaviors. Soon, audiences would extend the pass once exclusively given to the humorous and misguided and reward outright criminals fighting the establishment in The Public Enemy and Little Caesar (both 1931).

Audiences forgive Arabella and John because the two are only looking for a deserved break. They bend the rules a bit to counter life’s unfairness. Lots of people during the Great Depression did the same.

Forgiveness extends to other characters in Animal Crackers. Captain Spaulding, Ravelli, and the Professor all use humor to deflect dishonesty. Who are they trying to fool? Everyone, but they fool no one. Audiences see them as self-serving but harmless. The likable characters aren’t the only ones trying to fool people, either.

Class Resentment

The great art collector Roscoe W. Chandler, owner of the missing Beaugard, has an air about him, an air of deception. He’s not entirely honest about his background, although he can’t fool Ravelli. The conniving musician recognizes “Chandler,” a new persona crafted by Abe, the fish peddler from Czechoslovakia. Chandler/Abe is dishonest to others and, honestly, to himself.

Perhaps he feels his humble origins could hurt his appeal in high society. Dishonesty leads down a treacherous path, as Ravelli and the Professor’s lack of morals drives them to extort his silence. Chandler commits no crime. He’s the victim here. Still, he’s the antagonist to Ravelli and the Professor’s protagonists. Audiences likely resented Chandler’s desire to hide his working-class roots, an unforgivable act.

Class resentment lurks beneath the surface of Animal Crackers. Further, the scornful Grace and Mrs. Whitehead clearly represent the uncaring attitudes of the wealthy. This is shown throughout the film. Additionally, audiences revel in the Marx Brothers’ anarchic assault on high society. Even when comedians cause collateral damage.

Conclusion

People had little money to waste during the Great Depression, but many spent coins on tickets to Animal Crackers. The film was a cathartic working-class hit that struck audiences right in the funny bone. Maybe the dishonest and deceptive characters on-screen exaggerated what audiences wished they could do in real life.