Introduction

The car chase has been a staple in Hollywood for decades. So much so, they’re almost considered a “requirement” in certain action films. The Fast and the Furious, Mad Max, Jason Bourne, Transporter, and Terminator franchises, among others, are “expected” to showcase elaborate chase sequences built around mechanized vehicles.

In some cases, these bursts of adrenaline are executed with such precision and expertise that they stand on their own as works of art. Plus, they’re just plain fun.

While it would be impossible to do justice to every single memorable car chase in Hollywood history, we thought it might be fun to take an in-depth look at a few of them. Starting with the story of James Dean and the little-known connection between him and some of the famous on-screen “chases” that followed his untimely death.

James Dean

As a Hollywood icon, many people forget that James Dean starred in only three major films: East of Eden (1955), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), and Giant (1956). And of those, East of Eden was the only one released while he was still alive. At the time of his death in 1955 at the age of twenty-four, James Dean had already shown unbelievable promise as a new type of screen actor.

But acting wasn’t Dean’s only passion. He also loved cars and racing. As soon as he started getting substantial paychecks for his film work, he began buying race cars. An MG TD was his first purchase. And then came a 1954 Porsche 356 Speedster. Dean used these to compete professionally in several races in Southern California.

By the time filming on Giant had begun in the mid-1950s, Dean was the proud owner of a Porsche 550 Spyder. This made Warner Brothers, which was financing the production, a bit nervous. So, in order to protect their investment, they added a clause to Dean’s contract that prohibited him from racing while filming the picture.

Bill Hickman

It was during the production of Giant that Dean made the acquaintance of a gentleman named Bill Hickman. He was paid to be Dean’s voice coach in the picture. But informally, Hickman also served as a stunt driver and Dean’s racing buddy.

They even had nicknames for each other. Dean would call Hickman “Big Bastard,” while the stuntman returned the favor by calling the young actor “Little Bastard.” Dean adopted this latter name for his Spyder and had it engraved across the car’s rear cowling.

Later, Dean was eating at a restaurant in Los Angeles when he ran into actor Alec Guinness (Obi-Wan in the original Star Wars film). After the meal, Dean invited Guinness out to the parking lot so he could admire his custom-made Porsche. Guinness thought the car looked “sinister” and jokingly said:

“If you get in that car, you’ll be found dead in it by next week.”

A Bad Omen

The following week, Dean filmed his last scene on Giant. Told that he was no longer needed, Dean made preparations to travel to Salinas, California, to compete in a race. Originally, the plan was for him to travel with Bill Hickman and tow “Little Bastard” to the location.

But at the last minute, Dean decided he wanted more time with the Spyder and opted to drive it himself with mechanic Rolf Wutherich riding in the passenger seat. Hickman followed behind in a station wagon. The date was September 30, 1955, exactly seven days after Dean’s encounter with Alec Guinness.

The Accident

Late that afternoon, while driving on U.S. Route 466 near Cholame, California, Dean came across a 1950 Ford Tudor coupe being driven in the opposite direction by a 23-year-old student from Cal Poly. The Ford crossed into Dean’s lane to make a left-hand turn onto State Route 41. Wutherich told Dean (who, contrary to popular myth, wasn’t speeding at the time) to slow down. Dean replied:

“That guy’s gotta stop…he’ll see us.”

Those were James Dean’s final words. The two vehicles collided head-on, almost destroying the Spyder. Both Dean and Wutherich were thrown from the car, with Dean’s body smashing into the front grill of the Ford, headfirst. He suffered a broken neck and sustained massive internal injuries.

Wutherich landed on the pavement. He lay unconscious in a hospital for four days and took years to recover from a skull fracture and other broken bones. But the Cal Poly student (who wasn’t cited in the crash) only received a bruised nose and a gash to his forehead.

Death of an Icon

Meanwhile, Hickman, who had been traveling about three minutes behind them, arrived on the scene. He ran to where Dean lay dying and pulled him out from under the wreckage. Years later, he remembered those moments:

“…he was in my arms when he died, his head fell over. I heard the air coming out of his lungs the last time. Didn’t sleep for five or six nights after that…”

Later that year, Dean was posthumously nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, not just once, but for two different films: East of Eden and Giant. He remains the only actor to have ever earned that distinction.

For his part, Bill Hickman continued to indulge his passion for automobiles. When he wasn’t racing cars, he worked in Hollywood as a part-time stuntman and took numerous small roles in several feature films.

A New Kind of Car Chase

About a dozen years later, in 1967, Warner Brothers was intending to make a police drama starring sixty-seven-year-old Spencer Tracy. The original concept was to feature a laid-back detective who solved murders in between taking licks on an ice cream cone.

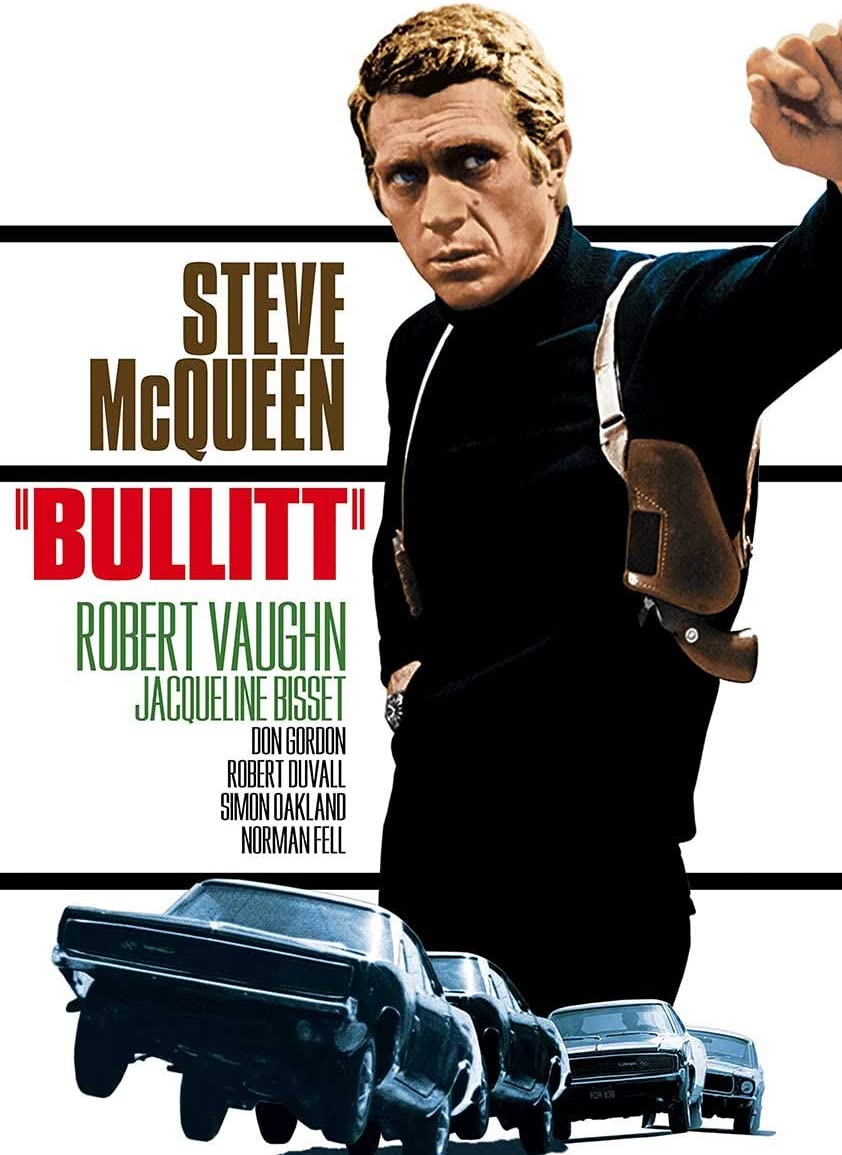

When Tracy ruined these plans by passing away suddenly, it was decided to take the film in a completely different direction. Steve McQueen was brought in as the star, and a new script was ordered. One that would be tough, gritty, and mean. And which would also feature a spectacular car chase designed to revolutionize cinema history.

Up until then, car chases at the movies were usually reserved for comedies and rarely lasted more than a few scenes. But for this new movie, called Bullitt, director Peter Yates and producer Philip D’Antoni wanted to go for realism while avoiding any fake-looking rear screen projections. McQueen was already a racing enthusiast.

To supplement the driving scenes, they also brought in the best professional stunt drivers they could find. One of them was Bill Hickman, who, in addition to helping with the choreography of the chase sequence, was to do all of his own driving as one of the hitmen that McQueen chases through the streets of San Francisco.

Filming Bullitt’s Car Chase

It took three weeks to film the segment, which lasts for over ten minutes on screen. McQueen drives a 1968 Ford Mustang, while Hickman is behind the wheel of a 1968 Dodge Charger. There were actually two Mustangs used during filming, and both were heavily modified to deal with the rigors of the shoot. The Charger also had extra work done on its suspension so it could withstand the jumps it made flying up and down the inclines of San Francisco.

Citing safety reasons, local authorities refused to allow the filmmakers to stage the chase over the Golden Gate Bridge. But for some strange reason, they were fine with a car chase racing through the center of the city. At times, their speeds reached 110 mph.

It’s great to see Hickman buckle his seat belt right before the chase takes off. On one hand, it’s a nod to his training as a professional driver. On the other hand, it’s a tip-off to the audience to prep themselves for a really wild ride.

Stunt Double

It’s also interesting to note that the stunt driver who doubled for McQueen was the same one who did the famous motorcycle jump for him in The Great Escape (1963). His name was Bud Ekins. When McQueen showed up on the set one day, he found Ekins with his hair dyed blonde.

Realizing that he wasn’t going to be allowed to do the dangerous portions of the driving himself, McQueen exclaimed, “You did it to me again!” (More trivia: Ekins also plays the motorcycle driver who spins out on the ground after the car chase leaves the downtown area and moves out onto a nearby parkway.)

A Car Chase For the Film History Books

The final result, on film, is truly remarkable. The editing, sophisticated camera work (including great alternating points of view from inside the cars), and sound effects combine to create an absolutely thrilling car chase. It’s over ten minutes long and is capped off by a spectacular explosion, which serves as a punctuation mark at the very end of the sequence.

When Bullitt was released, its car chase became the talk of the town and was the major reason the film won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing that year. In fact, most people can describe the car chase in complete detail. But just ask them about the rest of the movie, and you’ll usually just draw a blank stare. It’s proof of just how much this one sequence overshadows the rest of the film.

The Hickman Connection

Three years later, director William Friedkin wanted to duplicate this same type of edgy excitement while shooting his film The French Connection (1971). Specifically, he wanted to stage a truly thrilling car chase. One had Gene Hackman driving a 1971 Pontiac LeMans at breakneck speeds while chasing an elevated subway train in Brooklyn, New York. For his main stunt driver, Friedkin once again turned to Bill Hickman based on the latter’s reputation from Bullitt.

Hickman did the bulk of the driving and once again worked out the choreography. They decided to do all the filming “guerrilla style” and never bothered to tell the New York authorities what they had planned. However, after several days of filming, Friedkin wasn’t satisfied with the footage he was getting. He didn’t feel it was “exciting” or “realistic” enough.

So, he started goading Hickman to go for broke. Together, they mounted a camera onto the front fender of the Pontiac, and Friedkin climbed into the back seat to do his own filming. But not before surrounding himself with a full-sized mattress for protection. Hickman then drove 26 blocks under the raised train tracks in New York City at 90 miles per hour.

The only safety precaution taken was placing a flashing light on top of the car to warn unsuspecting civilians. What they filmed ended up being the majority of the footage making up the sequence. It was punctuated with staged bits, like the truck that crashes into the Pontiac, and the woman with the baby carriage that Hackman just barely misses. Later, Friedkin admitted that filming the car chase was entirely unsafe and now knows better, once stating he would:

“never do anything like that again…”

A One-Way Ticket to Jamaica

Another amusing story from that sequence was when Friedkin went to the New York Transit Authority to get permission to actually shoot the moving subway train. The official he met told him that what he had in mind was absolutely impossible. Not only because it involved deliberately crashing the cars, but also because it would promote an unsafe image for the New York transportation system.

When Friedkin got up to leave the meeting, the official called him back to make a suggestion. He told Friedkin that he would give the necessary approvals on two conditions: the studio would need to pay the Transit Authority $40,000, and it would personally provide him with a one-way ticket to Jamaica. Friedkin asked him why a one-way trip. The official replied that after he approved the shoot, he would need the ticket in case he got fired, which is precisely what happened.

Hickman Again

The third influential film, making up what some people refer to as the “holy trinity” of car chases, isn’t nearly as famous as the first two. Which is a real shame, since it can certainly hold its own with the others. The film we’re talking about is called The Seven-Ups (1973).

The film features an extended chase with Roy Scheider behind the wheel of a Pontiac Ventura while trying to catch a couple of bad guys driving a Pontiac Grand Ville. The latter car is driven by – you guessed it – Bill Hickman.

The car chase in The Seven-Ups takes place in the upper part of New York City’s Manhattan. And just as with Bullitt, you see the two cars racing up and down gradients through crowded city streets. Eventually, they cross over the George Washington Bridge and move onto the Palisades Parkway.

A Gritty and Realistic Car Chase

With Hickman as the choreographer, there are plenty of point-of-view shots as well as scenes where the camera travels parallel to the two speeding cars. In addition, there’s almost no dialogue or music. The screeching tires and roaring engines provide the soundtrack.

In contrast to sunny San Francisco, however, the sequence was shot during the wintertime, and as a result, all of the scenes are cloudy and gray. This further lends the chase an even grittier and more realistic feel.

It’s a superb show. But perhaps the reason this sequence from The Seven-Ups isn’t more widely celebrated is because of the ending to the chase. Roy Scheider’s car rear-ends a parked truck at top speed, which shears off the roof of his Pontiac. When setting it up, Hickman intentionally tried to recreate the 1967 crash in which actress Jane Mansfield lost her life.

It’s a shocking and violent conclusion to the extended sequence. However, the bad guys get away, and as such, this means that the chase turned out to be superfluous to the plot. As a result, this robs it of any lasting dramatic impact.

Bill Hickman’s Legacy

After The Seven-Ups, Bill Hickman continued to lend his car driving and stunt expertise to other films. They included Electra Glide in Blue (1973), The Hindenburg (1975), and Capricorn One (1977). He eventually died of cancer in 1986 at the age of sixty-five.

But Hickman’s legacy lives on. Having successfully demonstrated the potential for elaborate car chases, there were dozens of action directors and stunt drivers more than eager to follow in his footsteps. To the point where it’s now almost impossible to make a “best of” list. The James Bond films alone have enough examples to provide fodder for hours of discussion. Not to mention the game-changing nature of CGI in recent years.

More Classic Car Chases

Still, here’s a short list of some of our other favorites:

-

Mad Max: Fury Road

-

Ronin

-

The Blues Brothers

-

Death Proof

-

The Road Warrior

-

To Live and Die in LA

-

Vanishing Point

-

It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World

-

Raiders of the Lost Ark

-

What’s Up Doc?

Here are some additional titles for those interested in racing, to study the subject more in-depth. The following list is by no means inclusive. And not all of the films named are “classics.” But feel free to peruse and perhaps even add a few favorites of your own to the following list:

Bad Boys II, Baby Driver, The Cannonball Run, The Dark Knight, Death Race 2000, Die Hard With a Vengeance, Dirty Mary Crazy Larry, Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine, Drive, The Driver, Duel, Fletch, The Flim Flam Man, Gone in 60 Seconds, The Great Race, Hooper, Lethal Weapon, The Island, The Italian Job, Mad Max, The Master Touch, The Matrix Reloaded, Police Story, Short Time, Speed, The Sugarland Express, True Lies, Smokey and the Bandit, Viva Las Vegas, Wisdom, and Driving Miss Daisy (joking… just wanted to see if anyone was paying attention).