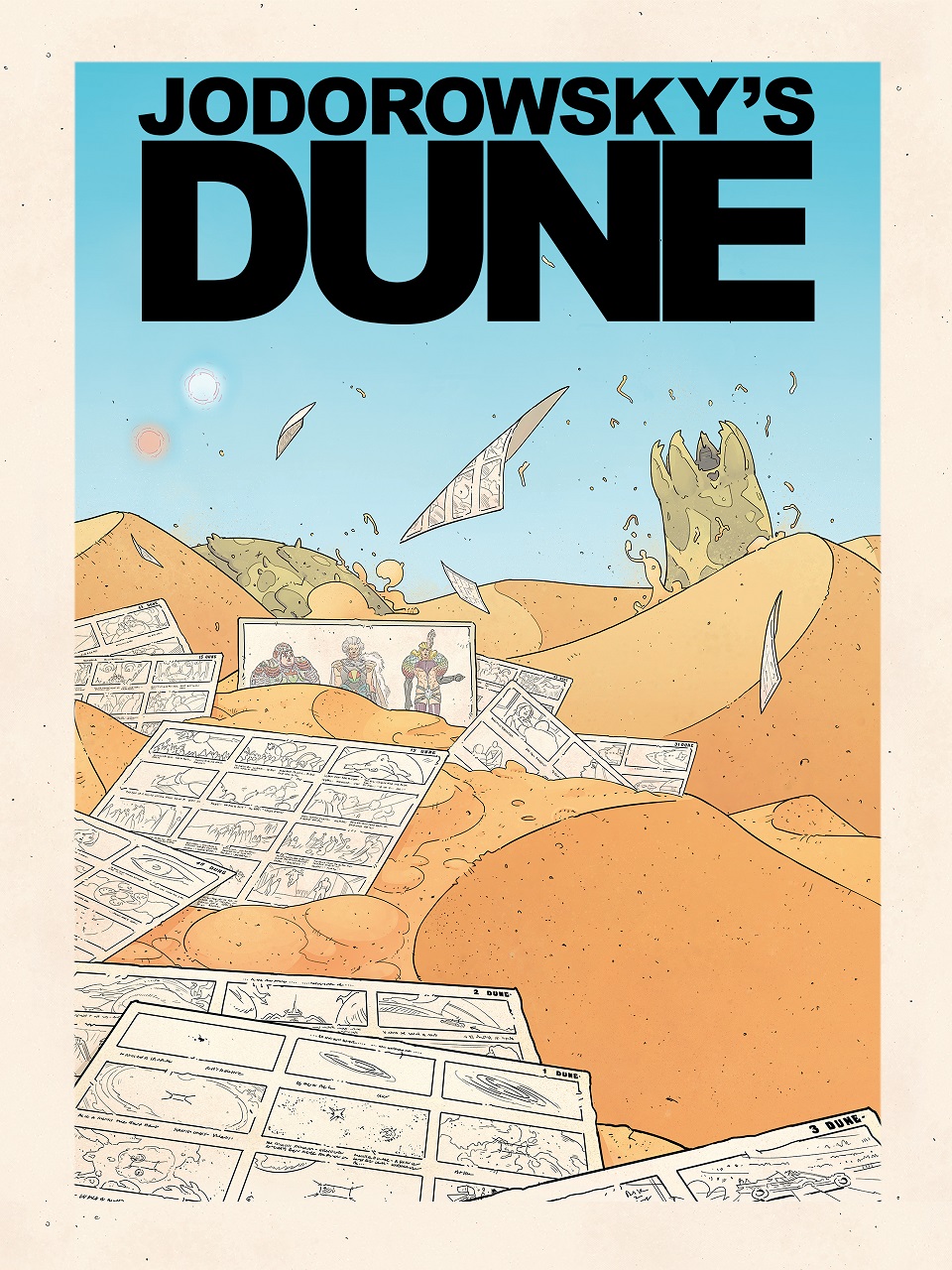

As we eagerly await Denis Villeneuve’s big-budget third film in the Dune franchise (to be released in 2026), we thought this would be a good time to revisit the film’s rich history. This includes a failed attempt in the mid-1970s to bring this famed science fiction novel to the screen. Besides Orson Welles’ Don Quixote, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune is probably cinema’s most legendary unfinished film.

Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert, the author of this epic tome, was already a veteran novelist, journalist, and political speechwriter when he wrote Dune in 1965. The genesis of this sprawling novel stemmed from a magazine piece he was researching in the late 1950s.

The premise of the piece was on how to control the flow of the sand dunes in Oregon. Herbert had amassed a mountain of research and had exclaimed to his literary agent that the moving dunes in Oregon could:

“…swallow whole cities, lakes, rivers, and highways…”

While Herbert’s article on the moving dunes was never completed, this research ignited a spark in him that would lead to five years of intense research and a three-part serial that would be published in the ANALOG Science Fact & Science Fiction pulp magazine. This was starting in 1963.

Herbert would go on to have a further five-part serial published a year later in the same magazine, called The Prophet of Dune. This would eventually become expanded, and published as the novel Dune in 1965 by Chilton Books. A publishing company known for its auto-repair manuals.

The Prophet of Science Fiction

Considering that Dune is widely considered to be one of the greatest “science fiction” novels ever written. It’s incredible how little “science” (and action) there is in Herbert’s novel. This was done on purpose as in the novel, humans revolted against technology and destroyed all thinking machines. As Herbert would state in an appendix:

“The god of machine-logic was overthrown, and a new concept was raised: ‘Man may not be replaced.”

This life-altering moment was known as the “Butlerian Jihad” and resulted in a spiritual awakening. This was an awakening that would put into place the religious structures that would ultimately produce Dune’s protagonist, and Christ-like figure, Paul Atreides.

Herbert wisely downplayed technology in his novel. Putting the main focus back on people, religion, and mysticism, which is not a common theme among science fiction novels. This type of science fiction would later become known as “soft” science fiction, a sub-genre of science fiction that tends to focus on psychology, sociology, and anthropology.

Frank Herbert’s writings throughout his lifetime were also heavily influenced by religion, specifically Zen Buddhism. Examples of this show up numerous times throughout the text of Dune.

Awards and Prestige

In 1966, Dune tied for the prestigious Hugo Award, which is given for best science-fiction or fantasy work. Herbert’s tome also would win the inaugural Nebula Award for best novel. Dune went on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide – becoming the greatest-selling science-fiction novel of all time. It has since been translated into dozens of languages.

Herbert earned widespread praise from the titans of the science fiction industry. This included Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein, Carl Sagan, and many others. Herbert would go on to pen five sequels, all of which are now considered science-fiction “classics.”

Alejandro Jodorowsky

In 1974, Jean-Paul Gibon purchased the film rights to Dune, and producer Michel Seydoux approached Chilean-French filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky (El Topo, The Holy Mountain) about bringing Herbert’s epic novel to the big screen.

For those who don’t know who Jodorowsky is, he is the absolute definition of a “renaissance man.” Jodorowsky has dipped his toe in just about every genre there is. He was, and still is at 92: poet, actor, comic-book writer, editor, director, musician, puppeteer, sculptor, psychologist, composer, mime, philosopher, and about a dozen other “professions.”

He has been called the first “cult” director, as his 1970 film El Topo was the first “acid-western” to be released. It became the first film to hit the midnight movie circuit in the US. John Lennon was so impressed with the film, that he convinced Beatles manager Allen Klein to put up $1 million for Jodorowsky’s next production, 1973’s The Holy Mountain.

Alejandro Jodorowsky met with Gibon and Seydoux and agreed to undertake the massive project of adapting Herbert’s novel for the big screen. However, he didn’t just want to merely adapt Herbert’s novel. Rather, (as Jodorowsky would later state in the 2014 documentary “Jodorowsky’s Dune“) he would spend the next two years of his life with the goal in mind to:

“change the public’s perceptions… change the young minds of all the world”

Spiritual Warriors

Jodorowsky’s Dune project began to take on a “mystical tone,” which was typical for most of his film projects. Seydoux had rented a castle outside of Paris for Jodorowsky to isolate himself and work on the script. When the script was completed, the director began to recruit his team of collaborators. Or his “spiritual warriors” as he referred to them.

The first of these warriors recruited was Jean “Moebius” Giraud, who was arguably France’s most prolific comic-book artist. Giraud quickly mapped out Jodorowsky’s vision and screenplay into storyboards. These were composed of over 3000 drawings.

For Jodorowsky’s Dune project, he had gathered his troops in Paris to begin work on the project. The artists that he assembled included visual effects mastermind, and screenwriter, Dan O’Bannon (Dark Star, Alien, Heavy Metal), and legendary Swiss artist H.R. Giger (Alien), who was recruited to create the visuals for the villain’s home planet.

British artist Chris Foss was also hired to create the film’s spacecraft. Additionally, Jodorowsky had lined up progressive-rock icon Pink Floyd (hot off the success of Dark Side of the Moon) to compose the film’s musical score, along with French progressive-rock cult band, Magma.

Stars and Celebrities

As for the actors that Jodorowsky had planned to star in the movie, it was a who’s who. Actors and celebrities that you would bump into on any given Saturday night at Studio 54. David Carradine, Mick Jagger, Udo Kier, Gloria Swanson, and even Orson Welles had all signed on to appear in Jodorowsky’s film.

For Welles, he only agreed after Jodorowsky had promised to buy him dinner every night in Paris during the film’s production shoot. Most incredible was that Jodorowsky had coerced legendary Spanish artist Salvador Dali to appear in his film. He was to portray “The Mad Emperor Of The Galaxy.”

Salvador Dali

Getting the unusual Salvador Dali to perform in front of the camera for the first time was a great get. However, Dali’s list of demands was excessive and…surreal. First, Dali demanded to be paid $100,000 per hour, which Jodorowsky agreed to. Consequently, the director worked with his cast and crew to make sure all of Dali’s scenes were filmed in one single hour.

Dali also wanted to have a throne that was made up of a toilet with two intersected dolphins on top. Dali’s dream of being the highest-paid actor in Hollywood was about to become a reality. Jodorowsky had also intended his then 12-year-old son Brontis to play the lead character, Paul Atreides; Brontis began to undertake extensive martial arts training, in preparation for the role.

Pre-Production Problems

While Hollywood had always intended Jodorowsky’s version of Dune to come in at around two hours running time, its director had a much different vision. He saw the film being 12-14 hours in length. While there was already a completed screenplay, a significant amount of financing secured, and the film was well into pre-production, this drastically different vision of the final product was going to be a problem.

Below is a fantastic clip from the 2014 documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune. In it, the director explains that Orson Welles was the ideal choice to play the slovenly and vicious Baron Harkonnen. Complete with anti-gravitational implants!

Jodorowsky and Seydoux flew to Los Angeles in 1975 to secure the film’s final $5,000,000 in financing. At the time, there were already rumblings in the air that things were beginning to go South. Regardless, Jodorowsky refused to budge on his vision. He would later say:

“For me, movies are an art more than an industry…for Dune, I wanted to create a prophet. Dune will be the coming of God.”

The End of the Line

Because Jodorowsky would never relent in his Ahab-like obsession with making Dune the 14-hour vision that he wanted it to be, you really can’t blame the studio executives who decided to pull the plug on the director’s massive production.

After almost three years of pre-production development, and a script that was the size of a phone book. Jodorowsky and Seydoux were unable to raise the final $5,000,000 to get Dune across the finish line, and production in Algeria ground to a halt. As Jodorowsky would later reflect:

“Almost all the battles were won, but the war was lost…The project was sabotaged in Hollywood. It was French and not American. Its message was not ‘enough Hollywood.’ There were intrigues, plundering. The story-board circulated among all the large studios. Later, the visual aspect of Star Wars resembled our style. To make Alien, they invited Moebius, Foss, Giger, O’Bannon, etc.”

What Jodorowsky says here is important and also on point. While we never got to see the director’s vision come to fruition back in 1975. Jodorowsky’s Dune had served as the embryo and starting point for other science fiction classics. Classics such as Alien (1979), Blade Runner (1982), and Star Wars (1977).

David Lynch

What we got instead nine years later, was a misguided film in David Lynch’s vision of Dune, released in 1984. With a budget of $40,000,000, Lynch’s film was a disaster at the box office as well as with critics. Lynch disowned the film, and in some cuts, Lynch’s name has been replaced in the credits with the name “Alan Smithee”

Alejandro Jodorowsky is still going strong in his 90s and trying to secure financing for his long-rumored sequel to El Topo, entitled The Son of El Topo. The time and effort that was spent on Jodorowsky’s version of Dune did not go to waste, as the director and Moebius used much of their designs, drawings, and concepts to create the French graphic novel The Incal. This was published between 1980 and 1988.

Also, there is a plethora of stuff online relating to Jodorowsky’s Dune. This includes interviews, journals, photos, animation, pages of script (that may be fake), etc. You can go down a deep rabbit hole researching all of this stuff.

The Future of Dune

With the release of Dune (2021) and Dune: Part 2 (2024), Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve undertook a massive production in an attempt to bring justice to Frank Herbert’s incredible vision. Dune (2021) was a critical and – somewhat – commercial success, grossing over $400 million worldwide on a $160 million budget. Dune: Part 2 grossed over $700 million worldwide on a $200 million budget. Villeneuve was able to finally, after fifty years of trying, bring Herbert’s vision successfully to the big screen.

Brian Herbert, son of author Frank Herbert, visited the Budapest set of Dune back in 2021, and later stated the following:

“…I was thrilled to actually be on the movie set in Budapest last year. Where my wife and I watched the filming of several scenes…This is a really big movie. A major project that will forever be considered the definitive film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s classic novel. Fans are going to love this movie. Denis Villeneuve is the perfect director to do ‘Dune…'”