Introduction

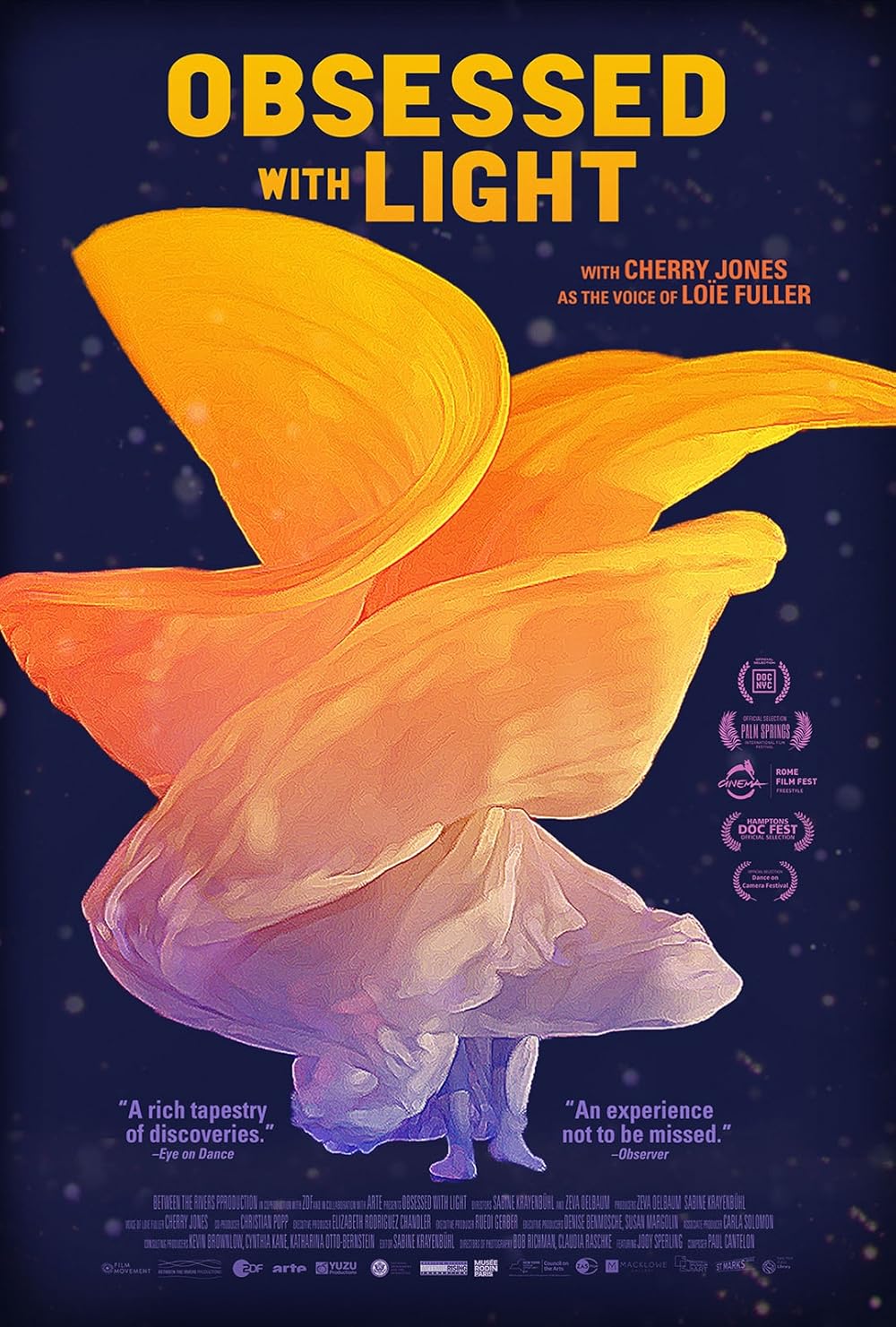

Obsessed with Light is a new documentary film that tells the story of American performer Loie Fuller (1862-1928), a pioneer of dance, stage lighting, and design. A meditation on light and the enduring obsession to create, the film pulls back the curtain on Fuller, a wildly original performer who revolutionized the visual culture of the early 20th century.

Creating a dialogue between the past and the present, Obsessed with Light delves deep into the astonishing influence that Fuller’s work has had on contemporary culture, including artists like Red Hot Chili Peppers, Taylor Swift, Bill T. Jones, Shakira and William Kentridge, among many others. In the process, the film uncovers commonalities that connect these creative luminaries to Fuller and each other.

Interview

Cinema Scholars’ own Glen Dower sat down with Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl, co-directors of the new documentary, Obsessed with Light. They discuss their approach towards making a documentary on the legendary pioneer of modern dance, Loie Fuller, the wide berth of modern artists Fuller has had an influence on over the past century, and the treasure trove of archival footage they uncovered, among other topics.

(Edited for content and clarity)

Glen Dower:

How are we doing Ladies?

Zeva Oelbaum:

Good. Thank you!

Glen Dower:

Now, I was taken in by the title immediately, and there was a circumstance that came about where I had to watch a portion of the film in silence, with closed captions. I was like, ‘Whoa, I think I might just watch the whole movie in silence!’ Did you approach it that way? Because we had the opening, of course, and the dance, and the dress, of course, like that. But I was just completely blown away. I paused and thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing!’ Like, play it again. So was that the approach you took for the rest of the film? If you can’t listen to it in sound, don’t worry about it.

Zeva Oelbaum:

That’s such an interesting observation. I mean, our interest is always in the visual, and, you know, early cinema, archival footage, and making things look as beautiful as possible. So it’s an immersive experience for the viewer. I don’t think we ever considered someone watching it without the sound on, but, interestingly, it works that way.

Glen Dower:

And my other senses were sort of taken in, because we have the colors, of course, and the opening, well, I felt so warm. Oh, and then changes color. Oh, that feels cool. And I was, I was completely drawn in. And then, of course, the narrative starts. So I’m interested to find out which of you ladies had the idea of the story of Miss Fuller. Who came to who with the idea?

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Well, I had worked on a documentary called ‘Picasso and Brock go to the Movies’ and that was a look at cubism and the influence of early cinema on cubism. And of course, it was at the same time as the Paris exposition, the famous fair where Loie performed. So there was that part of the thing. And so all these early films came up and the Loie Fuller film, or let’s say the Serpentine film, since we know that she was never filmed. Or we don’t have any film footage of her doing the Serpentine came up. And it was so startling to see this beautiful hand-tinted clip.

So, you know, we have always been interested in telling stories about women that have been forgotten in history. We just had finished a film about Gertrude Bell called Letters from Baghdad, and we were looking for a new thing. So we were thinking that Loie Fuller would be an incredible visual portrait or visual story to create and make come to life. But we discovered shortly afterward that she was also a very interesting character.

Zeva Oelbaum:

The other thing that we noticed right away when we were starting to research was that her name kept popping up in the most unusual places as an influence of William Kentridge, Alexander McQueen, and Taylor Swift. And, you know, we are very aware of wanting to make sure that the films have contemporary relevance. And so we’ve just felt that she checked all the boxes.

Glen Dower:

Yeah, for sure. And you have so many guests on there. I just looked at the IMDB and you have over, say, 10, or 12 guest speakers. How did you approach them and pitch the idea to them? Because, they all speak so passionately, and they love talking about Loie. So how did you pitch the idea? Or were they like, yeah, just sign me up?

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Well, it was sort of different with each person. Sometimes the person was introduced, you know, they had been influenced or inspired by the actual film clip, but they had no idea who Loie Fuller was. So as we were talking to them, they were all in some way or another fascinated about her. Our approach as we were making the film was especially guided also by their interests. Some of them were interested in the fashion aspect of it. Some were interested in her and what she represented as a woman at that time being so open about her body. And some of them were interested in the lighting aspect of her work. That’s what makes her so interesting. That was our approach. Finding people who could speak to the different aspects of her life and work.

Zeva Oelbaum:

And each person we tracked down, as Sabina said, had an explicit influence. In the case, for example, of Iris Van Herpen, we knew that she had done the cape for Jordan Roth, which seemed very Loie Fuller to us. And we knew that on her website, she talked about being trained in classical dance. So we reached out to her. And in fact, she’s a fabulous person who’s been influenced by Loie Fuller.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

One thing else I just wanted to say, that was important for us, which sort has become the overarching theme of the film, is creativity. How you work with inspiration and influence, and how that translates into new work. So that, again, also was really important to not only show how that affected Loie and how she worked, as well as all these different artists and fashion designers and all these different contemporary people.

Glen Dower:

Absolutely. And I just noticed the two, sorry, the three areas that she worked on her pillars if you like. Dance, stage lighting, and design. Going into this, people would say, well, these are three different disciplines. Would you agree with that going into the film yourselves?

Zeva Oelbaum:

Well, I think that when we first started to get more information about her and did more research on her, it seemed like they were very distinct. But in fact, they are all a piece of her creative process. Just the fact that she had the idea when hearing about the discovery of radium. ‘Oh, that would be interesting to apply that to the fabric of my costumes.’ It was her curiosity in all these different areas that led her to be so innovative and work with Tiffany’s for gels. So her driving force really was her embrace of new technology, and her willingness to take risks. And I think that we’ve seen this consistency with basically everything she did.

Glen Dower:

Yeah. And it’s about the making of it. It’s like building a documentary if you like. So, one of the moments I just stopped and went, ‘That is awesome’ was the flipbook that was shown. Was that a nice surprise for you? I was like, ‘Oh, we have a treasure trove here.’ Were there other different parts in the research process you came across moments like that?

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Yes, it was a combination of things that we didn’t know beforehand. In this case, it was interesting that Basil Twist mentioned it as one of the things that he had seen. But we discovered a man in Paris who had been an avid collector of these. And it turned out that there were many different versions of the Serpentine Deeds. That was also very interesting. So in that case, it was sort of a combination of we had already put our feelers out, and we happened upon this collector. And then Basil Twist mentioned it as his influence. So what a perfect convergence of themes. So, yeah, we discovered things.

We were, sometimes it was a real surprise to us. One of the biggest surprises was when we found the original tapes that were recorded, were recorded interviews with the dancers, with Louis Fuller’s dancers. And that was sort of, was very exciting, because, you know, as you saw in the film, we don’t have a lot of Louis Fuller herself, so but to have a firsthand account recorded on tape, so we had those tapes, they were little audio tapes, the ones that you have in a Walkman, we had them restored, and they were discovered at the Maryhill Museum of Art, which holds a very big archive of Loie Fuller.

Zeva Oelbaum:

And they had never been transcribed before. So that was exciting to us. One other thing was that we found a man, a professor in Germany, who has a collection of Sears and Roebuck catalogs. And we saw that one of the most successful clips was of the Serpentine Dance. And that sort of helped explain her fame in the late 19th century and early 20th century here in the States. In these tiny, tiny towns like that, we saw evidence in the newspaper archives in these tiny locations in the States.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

One thing that is interesting about those flipbooks is that they came after the film because they had the film frames in them. Yet, they are made of individual frames. So they are more related to Edward Muybridge and Marais, which is this sort of individual frame that they came later. In German, they are called Daumenkino, which means ‘a cinema with the thumb.’ So it’s just so interesting that this was a sort of take-your-cinema home in your pocket.

Zeva Oelbaum:

And they were in real-time at the time. And they’re all labeled Loie Fuller, even though none of them are actually Loie Fuller.

Glen Dower:

So she’s like a brand. That’s fascinating. Some of the keywords I wrote down relating to your film were mesmerizing, dimensions, kinetic, and beauty is expression. I underlined that. Sometimes, did you stop in your tracks when you were making the film and listening to the different – I don’t want to say talking heads – but the guests? One point where I stopped was around one hour and twelve minutes in. We meet Ola. She’s in a black dress and she’s performing. I could just watch that on repeat. It was just wonderful to watch.

Zeva Oelbaum:

Well, Ola, who is an amazing, amazing performer provided us with those film clips. So we did not shoot her. But what was incredible about her performance, and her interview, is that she mentions that Loie Fuller’s performance was like a Rorschach test. We happen to have scans from a book of signatures, which must have been very popular during Loie’s time, where they would wet the pages and the signatures would bleed on the opposite page. So we were able to use one of the images right after Ola’s dance that relates to the shape of her dance and relates also to what she said, as a Rorschach test. I don’t know if you remember that little section. It’s a little snippet.

Glen Dower:

That’s amazing. So here at Cinema Scholars, we have lots of up-and-coming directors and lots of film graduates who want to start directing. And they’re always asking us, can you ask any directors about starting in documentary filmmaking? Can you give us any words of wisdom, words of advice, or where you started with your very first documentary, and how you would go about starting one today?

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Well, I would say you have to be passionate about what you want to do, because depending on what you’re doing, it may take you five or six years to finish it. And so I mean, in our case, that’s what it took us because not only were we doing archival research that, you know, brought us all over the world, and also caught up a little bit by COVID as well. But generally, I think that the most important thing for someone to embark on a journey with a documentary is to be passionate about what you’re doing and to be open, because you don’t know necessarily in what direction, it’s not scripted. So you can’t control it. So you have to be flexible, and you have to be open to follow where it takes you and then, you know, integrate and combine that and into what you’re doing into the work you’re doing.

Zeva Oelbaum:

Yes, I would say you have to love it. You have to love your subject, you have to fall in love. Because it’s like a marriage with your subject.

Glen Dower:

That’s a soundbite for sure. And about documentary filmmaking, I always ask this – and I’m so lucky and privileged to speak to so many documentary filmmakers like yourselves – I always ask how do you know when you have enough? How do you know when you’re done? How do you know when we go, okay, cut, let’s get into the editing suites? Is there a moment you just know? Or is it what you’re building towards?

Zeva Oelbaum:

Well, actually, in our case, we sort of do each process sort of hand in hand, we get the archival footage, we get the primary source material, and we sort of fan out and go from one source to another person to another person. And all the while, of course, we’re inputting Sabina’s editing. So we’re, we’re, we have our process is sort of to do everything at the same time, you know, in a, in a way that is a little bit different. Also because of our work, films are historical primarily have a half historical subject and focus on focus on archival footage. And you’re shaking your head, Sabine.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Yeah, it’s not so different. It’s almost like it is with archival films. I would say in general, it has to go hand in hand, because, especially with our filmmaking, we make the story come alive through the archival image. We’re not just showing what’s being said, we’re trying to create an environment with archival footage. So it demands a search that goes far and wide. And sometimes what we’re building in the story informs what we’re looking for in the archives. And sometimes what we have found in the archives informs how we do the story.

So, it sort of goes hand in hand with archival searching and finding things and completing, completing the scenes or the sections. That’s how we work. And I think, in a way, you could always keep on tinkering and working on the film. But also, sometimes, it helps to have to sort of try to stick to your deadlines. In our case, we were also working closely with our co-producer, ZDF/Arte in Germany.

And then you have a little bit of a deadline to finish it. But we also set ourselves some limits in terms of how we were telling the story. I think when you have the biography of a person. When you have the life of a person, then obviously can go in many different directions. But our focus was really on her work and how the work influenced everyone around her then, and now. And so that gave us a little bit of a limit where we could say, okay, we got it. We got that section.

Glen Dower:

I like that. Move on. What are you working on next? Can you tell us about anything?

Zeva Oelbaum:

Percolating. We’re in the percolating phase, which is very necessary and productive. At least it might be productive.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Yeah. And also we are, basically, a two-woman show. So we do everything, even distributing. We have so much on our hands that it’s very hard even for us to start a new project, you know? Because we’re just doing everything. We’re involved in all aspects. So that’s also why we have to sort of recover and then find a new thing.

Glen Dower:

Well, thank you so much for your time. My time is up, but it’s been a real pleasure meeting you and I thoroughly enjoyed Obsessed with Life. Thank you so much for your time, ladies.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Thank you. Can I just ask a quick question? Where are you located?

Glen Dower:

I am in Doha, in Qatar.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Oh, wow.

Glen Dower:

It’s ten past six in the evening over here.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Right. But, the magazine that you publish, is it an international magazine, or is it a British magazine or is it Northern?

Glen Dower:

We’re based in the US. I’m originally from Ireland, as you might be able to tell from my accent, but I’m educated in the Middle East. So I’m multinational. But Cinema Scholars is based in the US. We have a website and a YouTube page as well.

Zeva Oelbaum:

Right. That’s lovely.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

Yeah.

Glen Dower:

Action-packed. But I did want to say that I work in education and I watched the movie for the second time today. And I immediately thought, ‘I’m gonna send this to my colleagues in my art department!’

Zeva Oelbaum:

Are you with Northwestern? Or which university are you affiliated with?

Glen Dower:

I work in a high school. We’re called the Newton Group in Qatar. So Newton International Schools. We have a group of nine schools, and I’m hoping to put on a film festival, where all the English department students do a mini-film based on their set texts. So it could be a poem, it could be a play. I want the performing arts to take off here. It’s not a big deal in the Middle East. It’s not their culture. But I’m trying to infuse them with this.

Sabine Krayenbühl:

That’s great. All right. Well, nice to meet you. Thank you.

Zeva Oelbaum:

Bye bye.