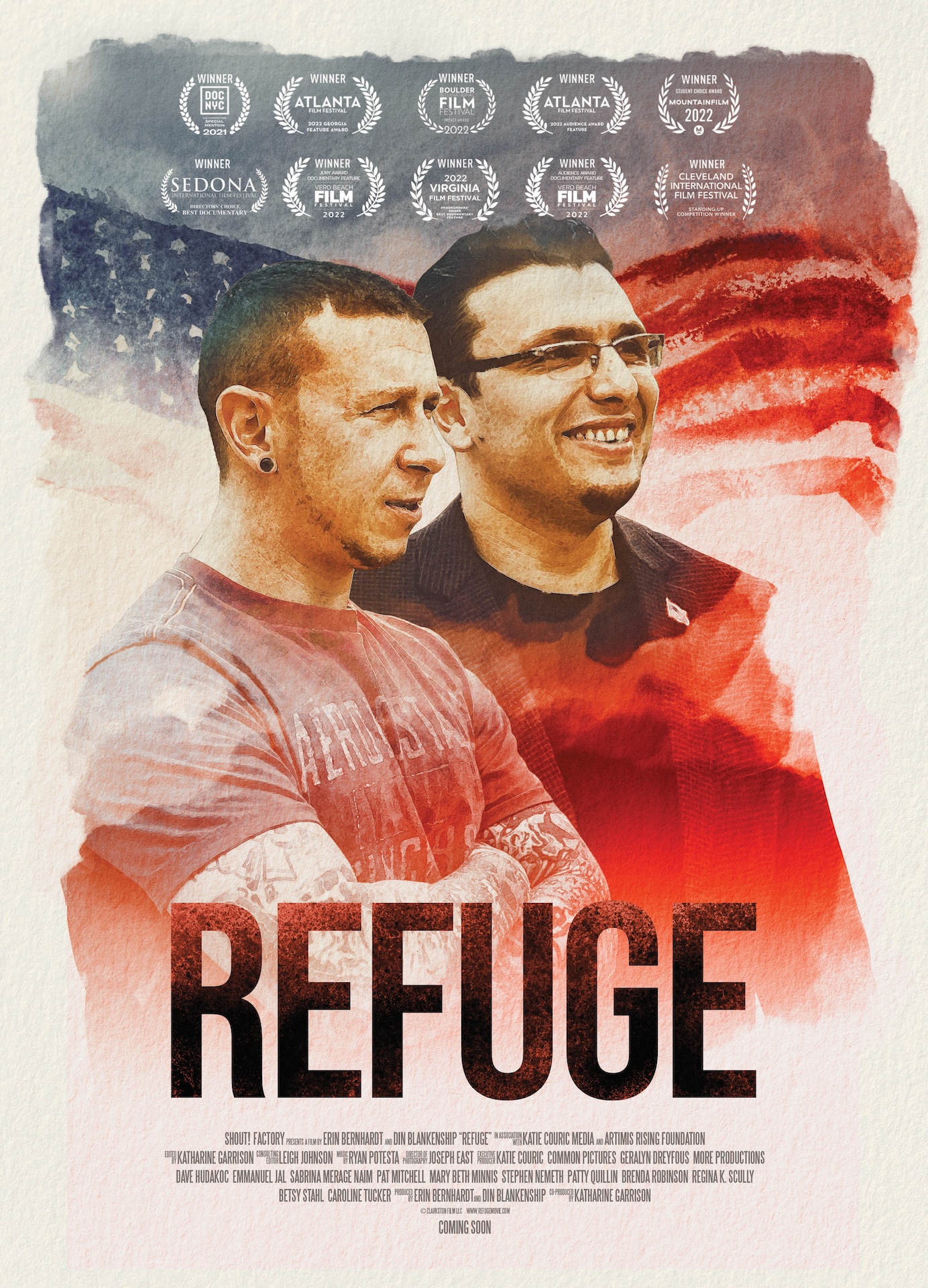

Cinema Scholars interviews co-director Din Blankenship about making the compelling documentary, Refuge, executive-produced by Katie Couric. Refuge is available to watch now on iTunes, Amazon Prime, and other major streaming platforms.

Introduction

Every year a slew of social commentary documentaries hit theaters. Or more often, the various streaming platforms are now available for smaller projects. It’s wonderful that these films can find an audience online, yet many disappear among the countless options available. Though many of these films have a vital message to convey, they lack the hook that reels people into actually caring about the subject. In most cases, this “it factor” is found in a personal connection to the story, rather than simply learning information. When a documentarian finds a compelling combo of platform and personality, the result is a project the audience can learn from as well as relate to.

In the documentary Refuge, filmmakers Erin Levin Bernhardt and Din Blankenship originally set out to highlight the unique story of a refugee town in the heart of Georgia. Eventually, however, an unexpected narrative emerged as a new friend of the community bravely faced his racist past and embraced his new neighbors and diversity. Rarely do we find a film that not only tackles social injustice but also features real-time redemption for one of its main characters. Refuge stands high above most commentary docs by achieving both with potent poignancy.

When we meet Chris Buckley, the former soldier and family man is in the aftermath of leaving the KKK. Disillusioned after tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, Buckley unfortunately found the camaraderie he craved among the members of the notorious hate group. Now, encouraged by his wife, Melissa, as well as a specialized interventionist, Buckley leaves the KKK and embarks on a new journey embracing the diversity he once feared. Along the way, Buckley is introduced to Dr. Heval Kelli, a Kurdish refugee and local cardiologist who resides in the resettlement community of Clarkston, GA. As their friendship slowly blossoms, they both confront their misconceptions and come to a better understanding of each other and their respective struggles.

Cinema Scholars’ Rebecca Elliott recently sat down with co-director Din Blankenship to discuss making the Refuge. They chat about going with the documentary flow, winning the trust of your subjects, and how you know when your film is finished.

Interview

Rebecca Elliott:

Hi Din! I’m very happy to talk to you.

Din Blankenship:

Yeah. Me too.

Rebecca Elliott:

I recently got to go to a screening of your film Refuge here in Austin, Texas. It was hosted by one of your executive producers, Mary Beth Minnis, with one of your main subjects, Chris Buckley, in attendance with his darling children. What a powerful film and an incredible screening. Thank you so much for taking time out of your busy schedule to talk to me about Refuge. Your story takes place in the context of Clarkston, Georgia, a refugee community outside of Atlanta. I understand that initially, you guys set out to focus more on Clarkston itself, but then this other narrative emerged with Chris. Can you talk about, especially as a documentary filmmaker, how you kind of have to go with the flow? What it’s like to shift gears in the middle of a project like that?

Din Blankenship:

Yeah, absolutely. So when we set out to capture this story, we were focused on this refugee community in Clarkston. This was 2017. The riots in Charlottesville, Virginia had just happened. And we felt like there was this rise of white nationalism in our country, and we didn’t understand why that narrative was resonating with so many people. We wanted to offer a kind of counter-narrative to white nationalism. If white nationalism was saying that immigrants of color were threatening our communities or were harming our communities in some way, Clarkston just actively disproves that.

And we also felt like it’s a community of people who aren’t just radically different from one another and living peacefully alongside one another. For many of the individuals who are refugees, they were enemies in their home countries. Generations of people at war with one another are now living in Clarkston and choosing a life of peace. That felt radical when we considered how polarized our country is along with this rise of hate and extremism we’re witnessing.

And so we’d been filming in Clarkston for about six months when Heval, who’s one of our main subjects, calls us and said, “Hey, I was introduced to this guy, Chris Buckley. He just left the KKK, and he still really hates Muslims. And we’ve been talking, but I’m going to go meet him. Do you want to come?” We were like, um yes, we do! When we thought about just the spirit of the film and why we were on this journey in the first place, it felt like capturing the potential, or the potential to understand more about why these narratives were resonating with people and if they could be overcome and what that looked like. We felt like we might have the chance to do that. And so we shifted gears pretty drastically mid-production.

Rebecca Elliott:

Yeah, I can only imagine taking that leap must have been kind of scary. And then also for your subjects, you mentioned you had already been following Dr. Heval Kelli. But then how did you convince Chris and his wife, Melissa to let your cameras into their life for what I imagine turned out to be years, right?

Din Blankenship:

Yeah.

Rebecca Elliott:

Did it take a lot of convincing, or were they on board right away? Tell me just about that process.

Din Blankenship:

Yeah, that’s a great question. When Heval first shared with Chris, “Hey, there’s this documentary that I’m a part of, and they’d like to join me when we first meet. Is that ok?” I think we all thought this was a one-time thing, so he’s like, okay. And we pulled a fast one! We’re like, actually, we’re going to be a part of your life now in an intimate way.

But I think a big piece of documentary filmmaking in general is building trust with the people that you’re filming. And so a big piece of our work was to develop a relationship with Chris and Melissa in which they knew that they could trust us with their stories and with their vulnerability. We wanted to make sure that they knew, like all of the people in our film, that we cared about their well-being beyond any participation in our film.

So we spent a lot of time with them and we invited them into our homes and shared ourselves with them. Which, as an aside, I am from Alabama and an Alabama football fan, and I also went to grad school at the University of Michigan, and Chris is a big Ohio State fan. So I think the biggest difference we overcame might be in Chris’s acceptance of me as a Michigan and Alabama football fan! Anyway, that was a big piece of building a friendship with them and the trust that is part of that.

Rebecca Elliott:

That’s hilarious! But it also kind of plays into one of my other questions. You kind of have a symbiotic relationship with the subjects of Refuge. They provide the heart to this commentary that you’re trying to portray. But you also provide for each other a sense of accountability, both ways. Being in the doc keeps them accountable on their journey, because, I mean, it’s not easy for either of them to be open-minded and accept the other. But their vulnerability could also keep you accountable as well. Can you talk about the symbiotic relationship and dynamic with the subjects?

Din Blankenship:

Yeah, that’s a good question. Initially, my mind goes to just, what’s the word? Like, the power imbalance. The power that we have as filmmakers to shape the story creatively. We could portray them however we wanted. I think it felt really important to us that their perspective, their experience, and their worldview were being represented accurately. And also that that was taking priority over our perspective and our worldview.

But in terms of accountability, we shared rough cuts and got their feedback to get a sense for, like, do you feel that this is an accurate portrayal of your experience and your life? So that was an important piece of it. Creatively hearing from them and hearing in what ways, I felt like we were getting it right. And in what ways could it be a better reflection of them?

Rebecca Elliott:

That’s a great answer to kind of an ambiguous question! I appreciate it. I’m sure you have countless hours of footage from this film, and I have to wonder, were there sub-narratives that didn’t make the final cut that kind of broke your heart? Or were you able to maybe play on some of those sub-narratives and turn them into other projects? I’m sure there were lots of stories in Clarkston that you had to let go of.

Din Blankenship:

Because we had started with the project focused on the community of Clarkston, we had characters in the film that we thought would be in the film, but whose stories didn’t fit into what it became when Chris entered the picture. So, you know, every time we had to cut a second of Mama Amina [Osman] out of the film felt like, “Don’t make us do it!” She could have a feature-length story all on her own. Losing bits of her every time we had to felt devastating.

There’s also an incredible young woman that we filmed. Her name is Bawi [Lian Par], and she is a refugee from Myanmar. And the story that we captured of her is amazing. And we have this short film that we’re desperate to finish and release out to the world just because she’s an incredible young woman. We filmed with her during her senior year of high school. When she got to the US, she was in fifth grade and spoke no English.

When we met her during her senior year, she was the valedictorian of her graduating class and got a full-ride scholarship to college. Just an amazing young woman, so we’re excited to be able to launch her story into the world. Because having to remove her from Refuge felt just disappointing when, you know, she has so much insight to offer us.

Rebecca Elliott:

Another great story that has to be told somehow, but not in Refuge. But as a filmmaker, you have to make those tough decisions. It still has to be an entertaining film that people want to watch to get the message across. So on that note, one of the things I loved about the film was your great animation sequences. They help to flesh out some of the stories that would otherwise just be talking head type of viewing. Can you tell me about the animation sequences and how you collaborated with your animator, Gina Niespodziani? I love how it was that beautiful sort of watercolor black and white look. It was gorgeous and also so compelling.

Din Blankenship:

Thank you. For both Chris and Heval…and Amina. She also had an animation sequence, but it was another thing that felt like we had to let it go. They each had a moment in their life that very much shaped the people that we were encountering in the film. Each of them involved violence trauma and loss. And so it felt like we needed to handle those moments with care, and they felt important for viewers to understand. This moment shifted the trajectory of this person’s life and very much impacts who you’re encountering right now.

But we felt like we wanted to represent them in a way that felt less like a depictive illustration of actual events, and more illustrative of what they experienced emotionally in that moment. And so watercolor felt like the right medium where we could be a little bit more emotionally expressive than a literal depiction of things. Our animator is just insanely talented. And so collaborating with her was an incredible experience. And I think so, too.

My background is in architecture, and so a lot of my background is generating imagery of, I have this thing in my head. What do I need to create image-wise to communicate that? So it was fun for me to be able to use that skill set that I developed in architecture for the film in that way. And so it was a pretty long process of where we started and where we ended with the animations of storyboarding and kind of laying out frame by frame and aligning that with the right voice-over so that visual and the VO weren’t saying the same thing. It was a long process, but our animator is just hugely talented. And so it was an enjoyable one.

Rebecca Elliott:

Well, it was great. Very effective and powerful. Well, I want to wrap it up, but I have to know. With a story this vast and ongoing, how do you know when it’s done?

Din Blankenship:

That’s another great question! We thought we were done a few times, and it turns out we were not. Well, there are two kinds of “done.” Like, okay, we can put our cameras down kind of done. Then there’s the “we’re picture locked and sending it out to festivals and kind of moving into the distribution phase” kind of done. With cameras down, we thought we were done before we were done. It became more clear once we were in the edit. Like, wait a minute, we got to keep following this. So there is an element of being open to recognizing if you do need to film more. And that was our experience.

Then there’s the “done with editing and shaping the story creatively in post-production.” I think that felt clear to us when we landed on the title. And we need to burn the evidence of all the terrible title ideas that we had throughout making this! I think we have, like, a 15 single-space page Google Doc of terrible title ideas. So bad. But when we think about it, what is this story at its essence? When you boil it down to its core?

It felt like a story about people seeking refuge, belonging, hope, identity, and purpose. I very much include Chris in that description. And also what it is to be a source of refuge for someone else? To be a source of hope, to be a source of welcome. And when we landed on our title, Refuge, that became clear. It helped us finalize some of those creative decisions. So we felt like, this is it. This is the thing. But that’s hard. It’s hard to know.

Rebecca Elliott:

Well, that wraps it up beautifully. Thank you so much for joining me today and talking about Refuge. I’m so excited to spread the word. Have a great day.

Din Blankenship:

Thanks. You too. Thanks again for helping us share about the film.

Refuge is available to watch now on iTunes, Amazon Prime, and other major streaming platforms.