Tracy and Hepburn

Spencer Tracy was at the top of his craft and a major player in the industry when he made his first picture with Katharine Hepburn in 1942. Hepburn experienced a resurgence in her career with her triumphant return in the classic, The Philadelphia Story (1940). This was after being famously labeled “box office poison” in 1938. The Tracy-Hepburn pairing and romance could have begun with that picture.

Hepburn acquired the rights to do a film adaptation of the successful Broadway show and had wanted Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy to co-star with her. When that wasn’t possible, the studio gave her Cary Grant and James Stewart instead. Their first movie together, Woman of the Year (1942), would be just as memorable. Hepburn later said of their first meeting on set that she “knew right away that she found him irresistible.”

The film was a romantic comedy about two journalists who find love and all the complications that ensue during their courtship and eventual marriage. The memorable scene when Tracy’s character walks into the office and lays his eyes on Hepburn from the legs up is still powerful. It’s also perfectly emblematic of how their relationship would develop—the chemistry between the two captivated moviegoers. With the smooth direction of George Stevens, the film was a smash hit at the box office.

Woman of the Year won an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. Hepburn also was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress. The accolades for the film continued decades later when it was selected by the Library of Congress in 1999 for preservation. This was due to it being “Culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” Although Tracy was not nominated for an Oscar, it was evident to everyone that MGM would reunite the pair for another film.

Romance and Controversy

The pair didn’t have to wait long for their second movie pairing. By the time filming had begun on Keeper of the Flame (1942), their budding romance was blossoming. However, with all the pressure Tracy was facing of carrying on an illicit relationship in secret along with his other personal demons, he had begun drinking again. Hepburn cared for him during his drinking binges during the production of the film.

The film is probably their most underrated collaboration. Based on a novel by Ida Alexa Ross Wylie, Keeper of the Flame is about a former reporter who plans to write a positive biography about a prominent civic leader. During his investigation, he discovers something suspicious about the man’s demise. This suspense thriller does not have the romantic fireworks of Woman of the Year. However, Tracy and Hepburn’s acting depth is superb.

The film was shrouded in controversy due to the circumstances surrounding World War II. Some members of Congress condemned the film’s leftist politics. It also led to calls for Hollywood to do more to curb propaganda in their films which seemed favorable to the enemy. While the film did turn a profit for the studio, it’s considered to be the least successful of their pairings. Director George Cukor was displeased with the film, though he singled out Tracy for praise saying:

“Tracy…was at his best in the picture. Subdued, cool, he conveyed the ruthlessness of the reporter sent to investigate Forrest’s death without seeming to try. He was ideally cast in the role…”

World War II

Tracy would have to wait until 1945 to do another picture with Hepburn. Between 1942 and 1945, he was busy appearing in war films. Most actors of the day were supporting the Allied war effort. Tracy also found time to work in the Hollywood Canteen to support the troops.

Of the films he did during this period, the tearjerker A Guy Named Joe (1943) with Irene Dunne stands out. Tracy plays the ghost of a dead pilot. He’s given the assignment of taking care of another young pilot played by Van Johnson (in his film debut). Tracy’s character grapples with the result that his former girlfriend (played brilliantly by Dunne), is now falling in love with Johnson’s character. The emotional ending, when Tracy recognizes he must let her go, exemplifies why his acting style is so revered.

The film was one of the top-grossing movies of 1944. Yet there was also controversy associated with its production. Tracy and Dunne had conflicts during filming. Part of this was due to Tracy making fun of her needlessly. On a positive note, Tracy and Dunne were patient and insisted that Van Johnson be allowed to remain in the film after he was injured in a severe car accident. While Johnson recovered, Tracy continued visiting the troops on their way to deployment. The actor visited hospitals, as well as performed on the radio for soldiers overseas.

Johnson and Tracy would reunite for the immensely popular Thirty Seconds over Tokyo (1944). In it, Tracy portrays the real-life hero General Jimmy Doolittle. The Hollywood Reporter declared the film to be “one of the greatest war pictures ever made.”

Post-World War II

The years 1945-1949 included four more collaborations between Tracy and Hepburn. By this time, Tracy had fallen out of love with his wife Louise. While Tracy had affairs with other actresses (including Loretta Young) throughout his career, his connection with Hepburn was profound. Still, he did not wish to divorce his wife, due to his Catholic upbringing. He also felt the guilt of leaving her alone to care for their deaf son, John. Tracy even rented George Cukor’s guest cottage where the couple would get together for quite some time.

Hepburn was in immense awe of Tracy for his acting ability. It’s also possible that their connection was because Hepburn found refuge in Tracy while coping with her own inner torment. As a young girl, Hepburn suffered the suicide of her older brother. It forever changed her. When they weren’t dining out together or spending time with friends like other couples such as Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, she cooked and doted over him like any other devoted partner.

Tracy’s drinking binges worsened when she was away or when he succumbed to his frequent bouts with Depression. Still, she always cleaned him up and took care of him. Also, their relationship was an open secret in Hollywood. When Hepburn was being investigated by the Congressional House un-American Activities Committee, the FBI kept a file on the couple, documenting Tracy’s drinking problems and Hepburn’s political activities.

A Return to Comedy

Without Love (1945) was a welcome return to comedy for Tracy and Hepburn. This was after the lukewarm public reaction to their last film together, Keeper of the Flame in 1942. Hepburn plays a war widow who still wants to help the war effort. She does so by marrying a military scientist on the premise that the marriage would be free of stress and jealousy if love was not involved! Hepburn took the role hoping to replicate her success from The Philadelphia Story (1940).

Hepburn had performed the role of the war widow on Broadway since Philip Barry had written the play with her in mind. He had also done the same for her with The Philadelphia Story a few years prior. The film achieved modest success and turned a profit for the studio. However, it did not generate the same buzz as Woman of the Year. One positive review came from Wolcott Gibbs from The New Yorker magazine who recommended the film. He stated that:

“…Miss Hepburn and Mr. Tracy succeed brilliantly in the leading parts…”

Tracy and Hepburn would team up again. This time to star in the western The Sea of Grass (1947), directed by the legendary Elia Kazan. Kazan’s enthusiasm for the project declined after having his hopes dashed of filming on location, as opposed to filming on studio backlots. Though it was the most profitable of Tracy and Hepburn’s pairings, the public reaction was mixed. Film critic Bosley Crowther of The New York Times commended Tracy’s performance as “impressive and dignified.” He did not, however, endorse the film.

A Growing Threat

State of the Union (1948) had all the ingredients for a successful film for Tracy. Originally conceived as a play that had a successful Broadway run culminating with a Pulitzer Prize win, legendary director Frank Capra and his team of screenwriters modified the script. This was intending to have Tracy play the lead. Capra intended Claudette Colbert to co-star with Tracy in the story about a man who’s inspired to run for the Presidency. Colbert, however, backed out after contractual issues. Hepburn came on board after Tracy persuaded Capra she would fit the role perfectly because of her stage background.

During production, there was intense acrimony on set. This is because long-time actor Adolphe Menjou was a cooperating witness for the Congressional House Un-American Activities Committee. This was a major problem since Hepburn and other prominent actors and writers were being investigated for possible communist sympathies. Nonetheless, the film succeeded, as it came out during the 1948 election season. Even President Truman saw it during the film’s premiere in Washington, D.C., as the guest of honor.

Adam’s Rib

If there was one movie that symbolized the Tracy-Hepburn movie screen pairing and real-life romance, it was Adam’s Rib (1949). In what was possibly their finest film together, the battle of the sexes in this exquisite romantic comedy is still timeless. The married duo portrays successful lawyers who have the misfortune of battling each other in a high-profile attempted murder case involving infidelity.

Hilarity ensues because Hepburn’s character was the one who ignited the fiasco. This is because she sought out the young defendant (played splendidly by Judy Holliday), insisting that she represent her. One classic scene is when one of Hepburn’s witnesses lifts Tracy off the ground during the court proceedings.

The climactic scene where Tracy threatens suicide in a jealous rage with a pistol (that in reality was licorice) is easily one of the best moments in a screwball comedy that classic Hollywood had seen in many years. The result was that Tracy and Hepburn made their most successful film together. It also generated a substantial profit for MGM. Movie critic Bosley Crowther wrote:

“…Mr. Tracy and Miss Hepburn are the stellar performers in this show and their perfect compatibility in comic capers is delightful to see…”

Credit also goes to George Cukor whose rapport with his leading ladies earned him the title of “woman’s director.” By this time, Cukor was very close to Hepburn and he had a front-row seat to the Tracy-Hepburn romance from its beginning.

Closing Out The 1940s

Tracy closed out the decade in an underrated film featuring another film heavyweight, James Stewart. Malaya (1949), was their second film together since Stewart made his film debut alongside Tracy in his first film with MGM, The Murder Man (1935). Since those humble beginnings, both men had reached the top of their profession. In addition, Stewart was eager to work with Tracy again. The plot is about two men who must work together on a government mission to smuggle rubber out of Malaya.

Malaya was not as well received as other Tracy vehicles from this era. However, all three leads were “acting in top form” according to Bosley Crowther of the New York Times. Stewart did his part to keep Tracy from relapsing into his well-known drunken binges. He even devised a plan in which he would arouse Tracy’s interest in taking a trip together to Europe. During filming, the pair would discuss visiting exotic locales along their journey. Tracy seemed genuinely interested. Stewart would later say:

“…the strategy seemed to work, and Spence showed up every day and did his usual fine job…”

To appreciate how much respect Tracy still commanded in the industry, he was billed first opposite Stewart. This was impressive considering that by 1949, James Stewart had successfully reinvented his screen persona. He had transformed into a darker and grittier image which aligned well with the post-war years since winning his Academy Award alongside Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story (1940).

Transitions

The 1950s proved to be a time of transition for Hollywood and Tracy. The Method style of acting, which emanated from New York City, began to shape Hollywood. Younger actors such as Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando, and James Dean would later make an indelible mark on the industry. The antihero, popularized by Humphrey Bogart, John Garfield, and Robert Mitchum, would also captivate movie audiences after the struggle of the war years.

America had come of age on the world stage. What worked so well before in Hollywood had to change to meet this reality. Would Tracy’s everyman persona and versatility adapt well to the evolving movie industry? In the 1950s, Tracy began the decade starring in a comedy-drama with one of Hollywood’s rising stars, Elizabeth Taylor, Father of the Bride (1950). Taylor at this point was transitioning from a successful child star into a glamorous leading lady.

In this classic, directed beautifully by Vincente Minelli, Tracy, and co-star Joan Bennett play the parents of the young Taylor. Tracy tells the story of his daughter’s engagement and subsequent marriage. The comedy was a blockbuster hit for MGM, earning $6 million worldwide. Variety magazine called it “the second strong comedy in a row for Spencer Tracy.” Bosley Crowther of the New York Times praised Tracy’s performance writing:

“…As a father, torn by jealousy, devotion, pride, and righteous wrath, Mr. Tracy is tops…”

Recalling his earlier success with Boys Town, MGM had decided to rush a sequel called Father’s Little Dividend (1951). Ultimately, the sequel was just as popular as the original. It also proved that Spencer Tracy was still a front-line star who could shine alongside the next generation of actors and actresses.

Art Imitating Life

In The People Against O’Hara (1951), Tracy portrays a successful defense attorney. After struggling with alcoholism, he must rebuild his life and career working as a civil attorney. His first opportunity comes when he is asked to defend Johnny O’Hara from a murder charge. Critics were not pleased, and the film had a mediocre showing at the box office. The film is noteworthy for resembling Tracy’s affliction with alcoholism.

As a testament to his versatility, very few actors could excel playing the father of a newlywed daughter in a comedy, and then receive praise for playing a recovering alcoholic within two years. That was what made Tracy special in the eyes of moviegoers worldwide. When you saw Tracy on screen, you saw yourself. He represented the common man trying to make it through the formidable challenges in life that we all struggle with.

Tracy and Hepburn would later reunite for their seventh screen pairing, Pat and Mike (1952). With George Cukor once again directing, the film was another romantic comedy with Hepburn playing a successful athlete who enlists the help of a sports promoter played by Tracy. Their bond and attraction for one another increase as he helps her overcome her inadequacies when competing in front of her fiance.

Hepburn considered this her favorite among all her movies with Tracy. The chemistry on set was helped by the fact that the script was written by Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon; close friends of Tracy and Hepburn. They rightfully believed the movie would be a good showcase for Hepburn’s athletic abilities and a good representation of her relationship with Tracy. Variety wrote about Tracy’s performance:

“Tracy is given some choice lines in the script and makes much of them in an easy, throwaway style that lifts the comedy punch.”

Critical Success

Pat and Mike featured appearances by several prominent athletes of the era. It also performed well at the box office. Just as with Adams Rib, Kanin and Gordon were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

Another memorable performance from Tracy came in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955). The action-packed drama featured an all-star cast including Walter Brennan, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, and Lee Marvin. Tracy plays a one-armed man who arrives in the town of Black Rock to bestow a posthumous military award to a local man whose son had died bravely during the Second World War. He immediately recognizes something mysterious is hidden there, and its residents will stop at nothing including murder to make sure that secret remains unknown.

Tracy’s performance earned him another nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actor. The film earned glowing reviews from critics who compared the film favorably to High Noon (1953). Bosley Crowthers of The New York Times characterized Tracy’s performance as the principal character as being “sturdy and laconic.”

Owing to the film’s fine performances and superb directing by the Oscar-nominated John Sturges, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress in 2018. Ernest Borgnine later said about working with Tracy:

“I was in awe of him. To me, he was the world’s greatest actor, and my God, here I am working with the man.”

Chemistry and Color

Tracy and Hepburn’s next screen pairing came two years later, in the office comedy Desk Set (1957). It was adapted to the screen from a successful Broadway play, In it, Tracy plays the inventor of the early-generation computer who is brought into a local library to plan its installation. Hepburn plays the administrator in charge of the reference department where the machine will be installed and later used by her and the staff.

She and her colleagues are reasonably concerned about their job security, and Hepburn’s character is initially not supportive of Tracy and his machine. The fireworks begin when Tracy’s machine inadvertently issues pink slips for the dismissal of the staff! While not as successful as their earlier pairings, their chemistry remains palpable. The film is also noteworthy for being their first film together in color.

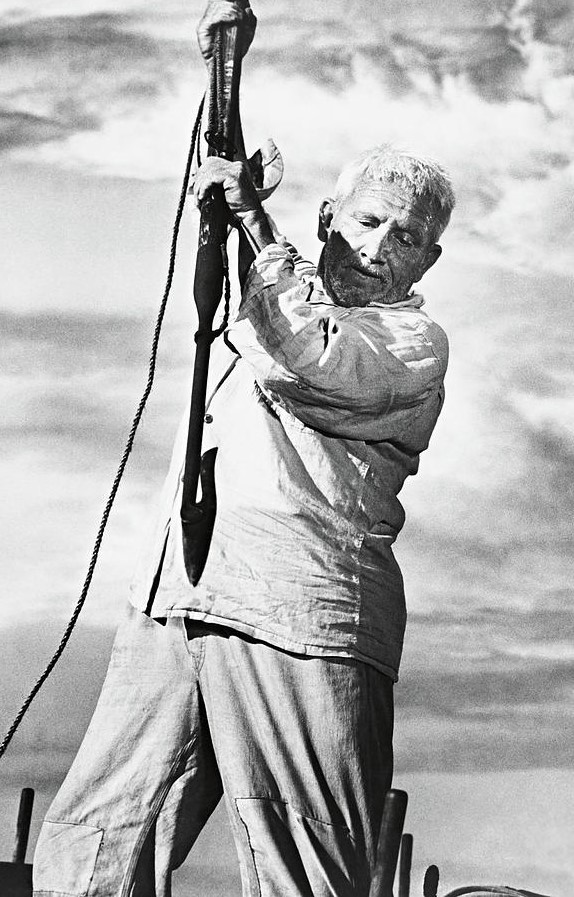

Tracy would next reunite with director John Sturges for another film adaptation of an Ernest Hemingway novel. In The Old Man and the Sea (1958), Tracy again plays a fisherman who must grapple with the duress of not catching a fish for eighty-four days, and his determination to bring in a much larger catch than he anticipated.

The film ran into significant production issues and went over budget. Hemingway also had concerns with Tracy’s believability as a Cuban fisherman. Still, he was satisfied with his performance. Anthony Quinn later stated that director Sturges preferred him for the role. However, the studio needed a bigger star such as Tracy. He was again nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor. Legendary composer Dimitri Tiomkin won the Academ-award for Best Original Score.

Reunions

In an ironic twist of fate, Tracy’s close friend Humphrey Bogart had tried to secure the film rights to the novel in 1952 but was unable to do so. Tracy performed superbly in the film which was released one year after Bogart’s death from cancer in 1957.

In 1958, Tracy reunited with John Ford who was responsible for allowing him to sign with Fox Studios in 1935. This next collaboration, The Last Hurrah (1958), was about an Irish American politician (Tracy), running his fifth campaign for Mayor in a New England town. The film was a significant portrayal of the complexities and corruption that is a lamentable part of politics. Tracy once again shined playing the aging incumbent mayor hoping for one last victory in office. Variety magazine wrote that:

“…Tracy’s characterization of the resourceful, old-line politician mayor has such consummate depth that it sustains the interest practically all the way…”

While the critics were almost unanimous in praise for Tracy’s performance, the film did not resonate with moviegoers at the box office. It recorded a loss of $1.8 million even though Tracy was once again nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor.

1960s

The final decade of Tracy’s legendary career began with the classic Inherit the Wind (1960). Directed by Stanley Kramer, this film was adapted from the 1955 play of the same name and was a fictionalized version of the events in the 1925 Scopes “monkey” trial. The film was a masterful portrayal of the real-life conflict between supporters of evolutionary science and religion. The original play and film were also conceived as vehicles to denounce the political intrigues of McCarthyism.

Featuring two of the most accomplished actors of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Spencer Tracy and Fredric March, provided many memorable scenes and dialogue. Gene Kelly who played a supporting role in the film marveled at the acting technique of Fredric March, and was in awe of Tracy’s performance, stating it was “like magic…all you could do was watch and be amazed.”

Tracy was again nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor, although Fredric March was not. In quite possibly his finest role, Tracy plays a judge as part of the all-star cast of Judgement at Nuremberg (1962), again directed by Kramer. The film is a poignant depiction of the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals in occupied Germany, after World War II.

Stanley Kramer masterfully directs a cast that includes such stars as Burt Lancaster, Montgomery Clift, Richard Widmark, and Marlene Dietrich. Maximillian Schell’s courtroom monologue is one of the great scenes in Hollywood history. It clinched the Academy Award for Best Actor. Judy Garland also turns in an impressive supporting role which garnered her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress. Kramer showed remarkable insight in casting another former musical star in another high-profile dramatic role.

A Master Craftsman

Brendan Gill of The New Yorker magazine commended the film’s cast writing “They all work hard to stay inside their roles.” Although Tracy lost out on the Academy Award for Best Actor to Schell, Harrison’s Reports wrote that Tracy gave “a performance of compelling substance.” The film grossed $6 million worldwide and altogether was nominated for twelve Academy Awards.

Spencer Tracy’s eleven-minute closing speech was filmed in one take. In addition, all the major performers did the film at a fraction of their salary since they all believed in the strong message of the film. Stanley Kramer told a story of how Spencer Tracy helped Montgomery Clift complete his scenes. In one difficult scene, Tracy told Clift:

“Just look into my eyes and do it. You’re a great actor and you understand this guy. Stanley doesn’t care if you throw aside the precise lines. Just do it into my eyes and you’ll be magnificent.”

It was apparent that Tracy’s battles with alcoholism could enable him to empathize with Clift’s struggles while still demanding excellence from himself and the cast. Tracy would have another successful pairing with Kramer as Director. This time, in the big-budget comedy, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World (1963).

Final Film

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), Tracy’s final film would be memorable because it would feature – fittingly – his final collaborations with Stanley Kramer and Katharine Hepburn. Kramer had shown his prowess in movies with social themes, and tackling the issue of interracial marriage was controversial at that time. Although Tracy and Hepburn flourished together in romantic comedies, this film would not have become a classic without them.

Tracy and Hepburn play a married couple whose daughter returns home from a vacation announcing her engagement to a black widower played superbly by Sidney Poitier. The daughter’s role was played by Hepburn’s niece Katharine Houghton. By this time, Tracy was in failing health. However, he insisted on completing the picture. He would later die of a heart attack seventeen days after the completion of the film.

In the film’s climax, Tracy’s final speech to both families approving the marriage of his daughter while tears are streaming down Hepburn’s face retains its impact even for modern audiences. Hepburn stated that she never saw the completed film, as it would conjure painful memories of her loss. Hepburn won the Academy Award for Best Actress, and Tracy was also nominated posthumously. It was a fitting end to one of the greatest careers in Hollywood history, and one of classic Hollywood’s most memorable romantic duos.

Transcendence

There were many great stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age. However, many of them were not as transcendent as Spencer Tracy was. His natural form of acting was ahead of its time since many of his earliest peers still adhered to the stage methods perfected on Broadway. It can be stated that Spencer Tracy introduced a form of acting versatility and range that paved the way for the likes of John Garfield, Marlon Brando, and James Dean.

Whether it was playing judges, attorneys, fishermen, or priests, Tracy did it with a style that captured the amazement and respect of his peers. There was nothing phony or unnatural about Spencer Tracy on screen. Burt Reynolds later said of Spencer Tracy:

“…I loved his style of dignity and class, and I have never been able to catch him acting. It’s like somebody just snuck a camera in. There is no doubt in my mind that he is the best actor in the world…”

Legacy

Like all of the greats, Tracy did have personal demons that affected his family and personal life. His drinking was compounded by inadequacies related to his guilt for his son being born deaf, and for not wanting to abandon him by ending his marriage to his wife Louise. There were rumors related to his sexuality first popularized by Scotty Bowers which further explains his emotional distress.

Whatever the case may be, it cannot be disputed that Katharine Hepburn truly cared for him even during his darkest moments. What can be appreciated is that despite these misfortunes he worked diligently at his craft while inspiring his peers and a generation of moviegoers. He was the first actor to win consecutive Oscars for Best Actor while amassing nine nominations. Tracy’s impact is still being felt decades after his death. In a 1986 tribute to Tracy, Robert Wagner said of Tracy:

“I’m a lucky fellow: a great man touched my life deeply. I was a mere lad in the shadow of this giant, but Spencer Tracy influenced me, inspired me, and gave me a sense of self-esteem. Everything I know about working hard and having standards, I learned from him.”

Tracy never liked to be the center of attention and would be embarrassed by such lofty praise. However, he would approve of Stanley Kramer’s memory of working with him: “He always said, ‘Take your work seriously, and yourself not at all.” That is the legacy of Tracy’s greatness. That’s why his work will continue to amaze future generations of actors and moviegoers.