This is the second part of our series on Mary, Jack, and Lottie Pickford. If you missed part one (Click Here) to read it.

Jack and Lottie in the Roaring Twenties

After returning to Hollywood after the death of his wife, Olive, Jack’s career in front of the camera slowed down with him only appearing in a few movies a year until he finally finished his acting career in 1928 with the release of Gang War. Although Jack was interested in writing and directing, neither of these pursuits was successful as his drinking and drug abuse got in the way.

On July 31, 1922, Jack married Broadway dancer and former Ziegfeld girl, Marilyn Miller at Pickfair. The marriage was not a happy one, primarily due to Jack’s spousal abuse and constant drunkenness. The couple separated in 1926 and Miller was granted a French divorce in November 1927.

Meanwhile, Lottie didn’t fare much better in either movies or in life. She appeared in only three movies in the decade with her final role being in Douglas Fairbank’s Don Q, Son of Zorro (1925).

Superstar Mary

Due to her superstar status, Mary leveraged her box office power into a new contract in 1916 with Adolph Zukor at the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation. The contract granted her complete creative control over any movie in which she starred. It also guaranteed her a salary of $10,000 per week ($275,000 adjusted for inflation), and half of the profits of each film she appeared in with a guarantee of $1,000,000.

Under this contract, she appeared in such hits as The Poor Little Rich Girl (1917), and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1917). Because of her small stature, she often played children, a trend that would continue well into her thirties.

After signing the contract in 1916, she worked with Constance Adams DeMille, wife of director Cecil B. DeMille, to found the Hollywood Studio Club. This was a dormitory for young women involved in the movie business. Prior to this, many young actresses resorted to meeting in the basement of the Hollywood Library to read plays and living in cheap hotels. The Studio Club closed in 1975.

1918 was a turning point in Mary’s life, both personally and professionally. First, her marriage to Owen Moore reached the breaking point. This was after years of strain caused by his alcohol-induced violence against Mary due to jealousy of her career success.

While on tour across America, promoting the sale of Liberty Bonds to support the war effort, Pickford began to get serious with fellow box office megastar Douglas Fairbanks. The pair had met at a party in 1915 and had begun to see each other causally about a year later. However, by the time the USA entered World War I, the relationship became more substantial. They would marry three weeks after her divorce from Moore became final, on March 28, 1920.

Professionally, Mary reached a contractual impasse with Zukor. He became so frustrated with her that he offered her $250,000 to leave the movie business forever. She refused and signed on with First National Pictures.

United Artists

Things weren’t so rosy over at First National either, especially for Charlie Chaplin. The actor was increasingly frustrated by what he deemed as insufferable management. This was due to lower budgets for his movies than he deemed to be acceptable. Chaplin had spoken with both Mary and Fairbanks, who were dissatisfied with First National and Famous Players-Lasky, respectively.

After talking to all three screen legends, Chaplin’s brother and business manager Sidney Chaplin convinced them to hire a private eye. This was to see if any information could be learned about why things had seemed “off” for the past year. They soon learned that First National and Famous Players-Lasky planned to merge, which would get them greater leverage over stars and their contracts since there would be in effect one less studio around.

As a result, Mary, Chaplin, and Fairbanks teamed up with D.W. Griffith to start their own film company. United Artists was founded on February 5, 1919. Each partner held a 25 percent stake in the preferred shares and a 20 percent stake in the common shares of the joint venture. The remaining 20 percent of common shares were held by lawyer and advisor William Gibbs McAdoo.

Prior to the formation of United Artists, movie studios were vertically integrated. This meant that they were producing films as well as owning chains of theaters. The studio’s distributors would then arrange for that company’s productions to be shown in their theatres.

United Artists was different in that it was just a distribution company. They allowed independent films to be shown in their theatres. This allowed the founders to have full creative control to make their own movies and then distribute them how they pleased.

In 1920, Mary and Fairbanks formed their own film production company, the Pickford-Fairbanks Studio. The studio was located on the corner of Formosa Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. In 1928, the name would change to the United Artists Studio. Both Mary and Chaplin would continue to produce films at the studio until it was sold in 1955, becoming the Samuel Goldwyn Studio.

Because life wasn’t busy enough for Mary and Fairbanks, they also decided to undertake the construction of a massive mansion in Beverly Hills. The house would take several years to complete and would be dubbed Pickfair. It gained legendary status almost immediately. (Click Here to read our article about this historic mansion).

The Twilight of Silent Films

As part of United Artists, Mary rattled off a string of self-produced hits including Pollyanna (1920), Little Lord Fauntleroy (1921), Rosita (1923), Little Annie Rooney (1925), and Sparrows (1926). Every one of these films made at least double their budget back.

Sound films arrived with first the first talkie, The Jazz Singer, premiering on October 6, 1927. Mary felt that this was a gimmick that wouldn’t last stating that:

“…adding sound to movies would be like putting lipstick on the Venus de Milo…”

Around this time Mary and Fairbanks partnered with theatre mogul Sid Grauman and Howard Schenck on his new project, Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. (Click Here to read our article about the history of this theatre). Mary was the first star to put her footprints in the theatre’s famous cement slabs in front of the theatre.

“When they (Sid Grauman, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks) stepped up off the curb, they accidentally walked on wet cement and left a trail of footprints from the street to the front doors of the theater…The stars, seeing what they had done, grabbed a nail on the ground and signed their names next to their footprints, Pickford even dated it.”

— Marc Wanamaker, Hollywood Heritage Museum

AMPAS

Meanwhile, MGM head Louis B. Mayer began to devise a plan to create an organization that would mediate labor disputes without trade unions, It would also improve Hollywood’s image with the public. After meeting with Conrad Nagel and a few other industry insiders, they decided that this organization should have an annual banquet to celebrate the film industry.

Mayer gathered a group of the biggest players in town, thirty-six in all (including Mary and Fairbanks) to a formal banquet at the Ambassador Hotel on January 11, 1927. At the dinner, Mayer presented to those guests what he called the “International Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.”

Each guest became a founder of the Academy. Prior to the filing of the official Articles of Incorporation for the organization on May 4, 1927, the “International” was dropped from the name, becoming the “Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences” (AMPAS).

After the first Academy Award Ceremony on May 16, 1929, the Academy began to store film prints and archival papers. Decades later, in 2002, the building where these documents were held was named The Pickford Center for Motion Picture Study.

Coquette

In 1928, Mary decided it was time to make a “talkie.” This was despite her previous remarks about them. She bought the rights to a new Broadway play, Coquette, which opened on November 8, 1927.

This would be the first time the world would see Mary with her now short hair. This was an adult role, much like what she played in her previous film, My Best Girl (1927).

Leaving little to chance, Mary had the most advanced sound equipment at the time, installed at the studio. Recording a sound film was extremely difficult because the sound equipment was sensitive. Any noise such as rattling jewelry could ruin a take.

The entire sound process was extremely stressful for Mary, who also produced the film. When hearing her voice on film for the first time she commented, “Why that sounds like a little pipsqueak voice!” She soon began to take voice lessons to sound better on film.

During a take, she fired her long-time cameraman Charles Rosher after he yelled “Cut!” during one of her lines because a shadow had fallen across her face. A short time later she realized her error and apologized in a letter saying:

“…Tragedy is an ugly mask. I don’t want to look like something on a candy box or a valentine…”

At the premiere of the film in New York on April 5, 1929, a fuse blew, killing the film’s sound. It had to be restarted twice for everything to work properly. Coquette was a success, earning $1.4 million at the box office. It also earned Mary an Academy Award for Best Actress on April 3, 1930, in Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel.

Mary’s Final Film Roles

For her next film, Mary teamed up with Fairbanks to make The Taming of the Shrew (1928). This would be the first adaptation of Shakespeare for the screen to be in sound. The couple’s marriage was starting to strain while making the film. Later, Mary would state that making it was the worst experience of her life.

“As a reenactment of the Pickford-Fairbanks marriage, Taming of the Shrew continues to fascinate as a rather grim comedy. The two willful, larger-than-life personalities working at cross-purposes and conveying their resentment and frustration to each other through blatant one-upmanship and harsh wounds is both the movie and the marital union.”

– Jeffrey Banks, Douglas Fairbanks Biographer

In 1930, Mary began to remake the Norma Talmadge film, Secrets (1924) with a new title “Forever Yours.” However, with the film nearly done with shooting, and expenses totaling over $300,000, Mary had all of the footage burned. She felt the film was terrible. Mary would eventually start from scratch and make the film again, with the title Secrets (1933). This would be her final role before retiring.

In between “Forever Yours” and the Secrets remake she would remake another Norma Talmadge film, Kiki (1931). It performed poorly at the box office and became the only Mary Pickford movie released by United Artists to lose money, earning only $400,000 at the box office.

Mary would retire from film acting in 1933. However, she would appear as herself in the short film, Night at the Cocoanut Grove (1934). This would be Mary Pickford’s only film appearance in Technicolor.

Prior to retiring, Mary had plans to team up with Walt Disney to create a hybrid live-action/animation film based on Alice in Wonderland, which would have been in Technicolor. However, Paramount secured the rights to the novel before they could on May 9, 1933, effectively killing the project.

It would have been more logical if silent pictures had grown out of talkies, instead of the other way around.”

– Mary Pickford

The End of Mary and Doug

Mary and Fairbanks were the Hollywood “It” couple at the time these films were made. In addition to hosting parties at Pickfair, the pair were treated as unofficial Ambassadors all over the world. Mary didn’t enjoy these events, or travel, which strained her marriage with Fairbanks further.

The marriage between Mary and Fairbanks was permanently damaged when the actress discovered her husband was having an affair with Sylvia Ashley. The couple divorced on January 10, 1936, with Fairbanks marrying his mistress soon after.

The Final Days of Jack and Lottie

In 1930, Jack married for the third and final time to twenty-two-year-old Ziegfeld girl Mary Mulhern. The marriage was not a happy one, ending two years later due to his continued abuse of the girl.

By the time of the divorce, Jack was in bad shape, emaciated, and a full-blown alcoholic. On January 3, 1933, Jack died in Paris, France. His death was listed as “progressive multiple neuritides which attacked all the nerve centers” due to alcoholism. He was just thirty-six years old.

Mary arranged to have her brother’s corpse brought back to Los Angeles. He was interred at the Pickford family plot at Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

Lottie didn’t fare much better during the end of the Jazz Age. The actress married twice more, first to an undertaker named Russel O. Gillard in 1929, and finally to a wealthy businessman from Pittsburgh, John William Locke, in 1933.

On December 9, 1936, Lottie Pickford died of a heart attack related to constant alcohol abuse. She was forty-four years old. Like Jack, she was buried at the Pickford family plot at Forest Lawn Memorial Park.

Mary Keeps Busy

After retiring from Hollywood acting following the release of Secrets, Mary continued to act throughout the mid-1930s. First, she appeared on stage in Chicago in 1934 in the play The Church Mouse. In 1935, she took on a tour of the stage play version of Coquette.

After the tour ended, Mary decided to jump into the world of radio. She first appeared in a series of plays for NBC in 1935. Mary followed this up with a series for CBS in 1936. She retired from acting completely when she became vice-president of United Artists while finishing up her work with CBS.

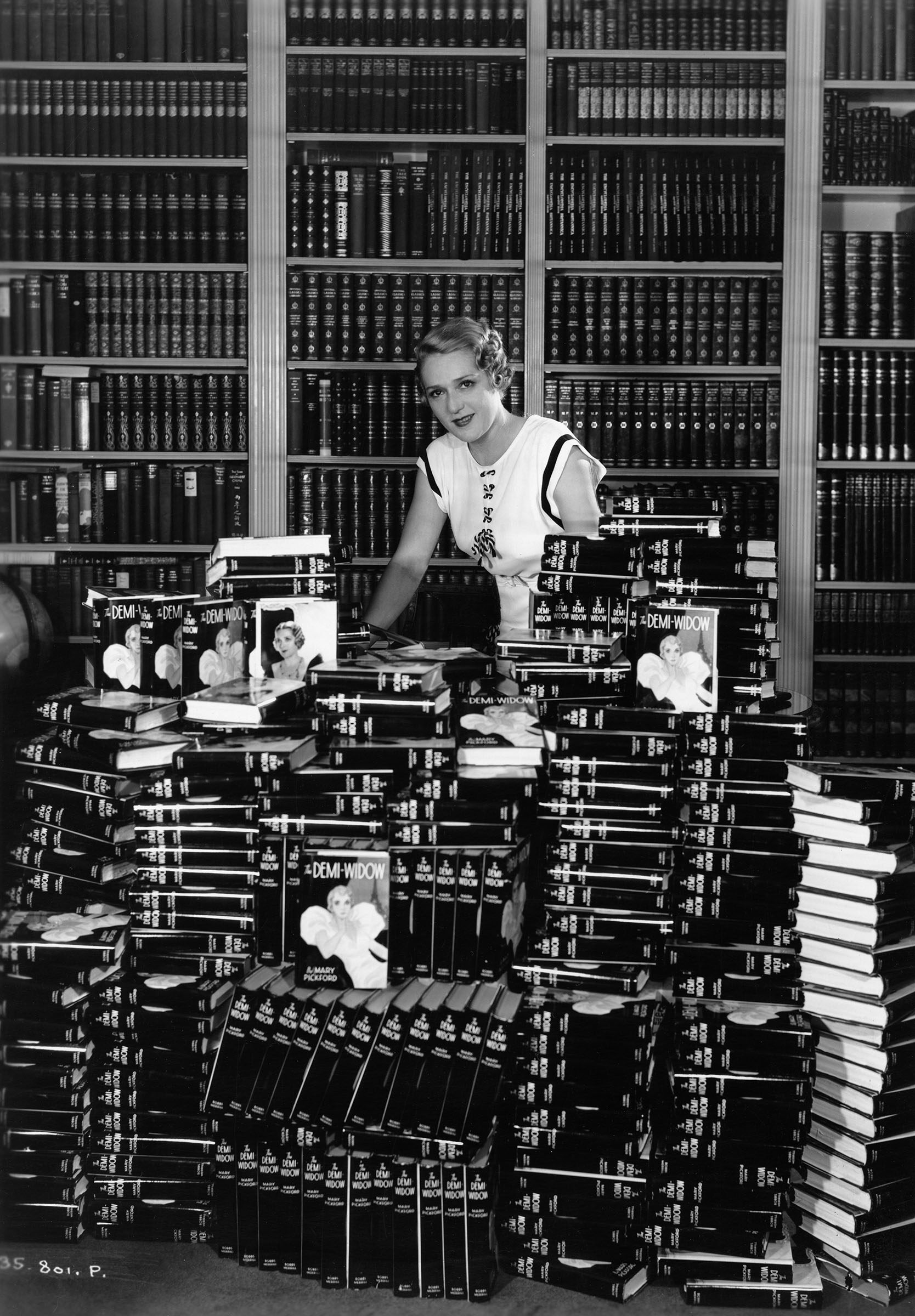

Mary also turned her attention to the written word. Her first published work was an essay on spirituality and personal growth in 1934 entitled Why Not Try God? The following year she published another essay, My Rendezvous With Life, about her belief in the afterlife. That same year also saw the publication of her novel The Demi-Widow. Finally, in 1955, she published her memoirs, Sunshine and Shadows.

In 1937, she married her My Best Girl co-star, Buddy Rogers. The couple would adopt two children in the early 1940s, Roxanne and Ronald Charles. Mary was extremely critical of these children, especially any physical characteristics that seemed to be imperfect.

“Things didn’t work out that much, you know. But I’ll never forget her. I think that she was a good woman.”

– Ronald Rogers

In addition to starting a family during the Second World War, she also contributed to the war effort. Along with promoting war bonds, she also made appearances in support of the Allies in both the United States and Canada.

Later Years

As the years passed, Mary became more and more reclusive, eventually only allowing Lillian Gish into her home as a visitor. Anyone else she only spoke with on the phone. Despite this, charitable events supporting World War I veterans were still held at Pickfair during this period.

In 1976, Mary was presented with an honorary Oscar, which she accepted at Pickfair. This event was televised as part of the Academy Awards broadcast, which offered viewers a glimpse at the inside of Pickfair.

On May 29, 1979, Mary Pickford passed away as the result of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 87. She was interred in the family plot at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale.

Legacy

“(Mary Pickford was) The best known woman who has ever lived, the woman who was known to more people and loved by more people than any other woman that has been in all history.”

– Adela Rogers St. Johns, Screenwriter

Mary Pickford appeared in over two hundred movies during her career while her sister Lottie and her brother Jack appeared in eighty-four each. The legacy of the family lives on with their filmographies while Mary’s also includes buildings dedicated to her as well as other items in public view such as her handprints in cement in front of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre and her star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6280 Hollywood Blvd.

“Today is a new day. You will get out of it what you put into it…If you make mistakes there is always another chance for you. You may have a fresh start any moment you choose, for this thing we call ‘failure’ is not the falling down, but the staying down.”

– Mary Pickford