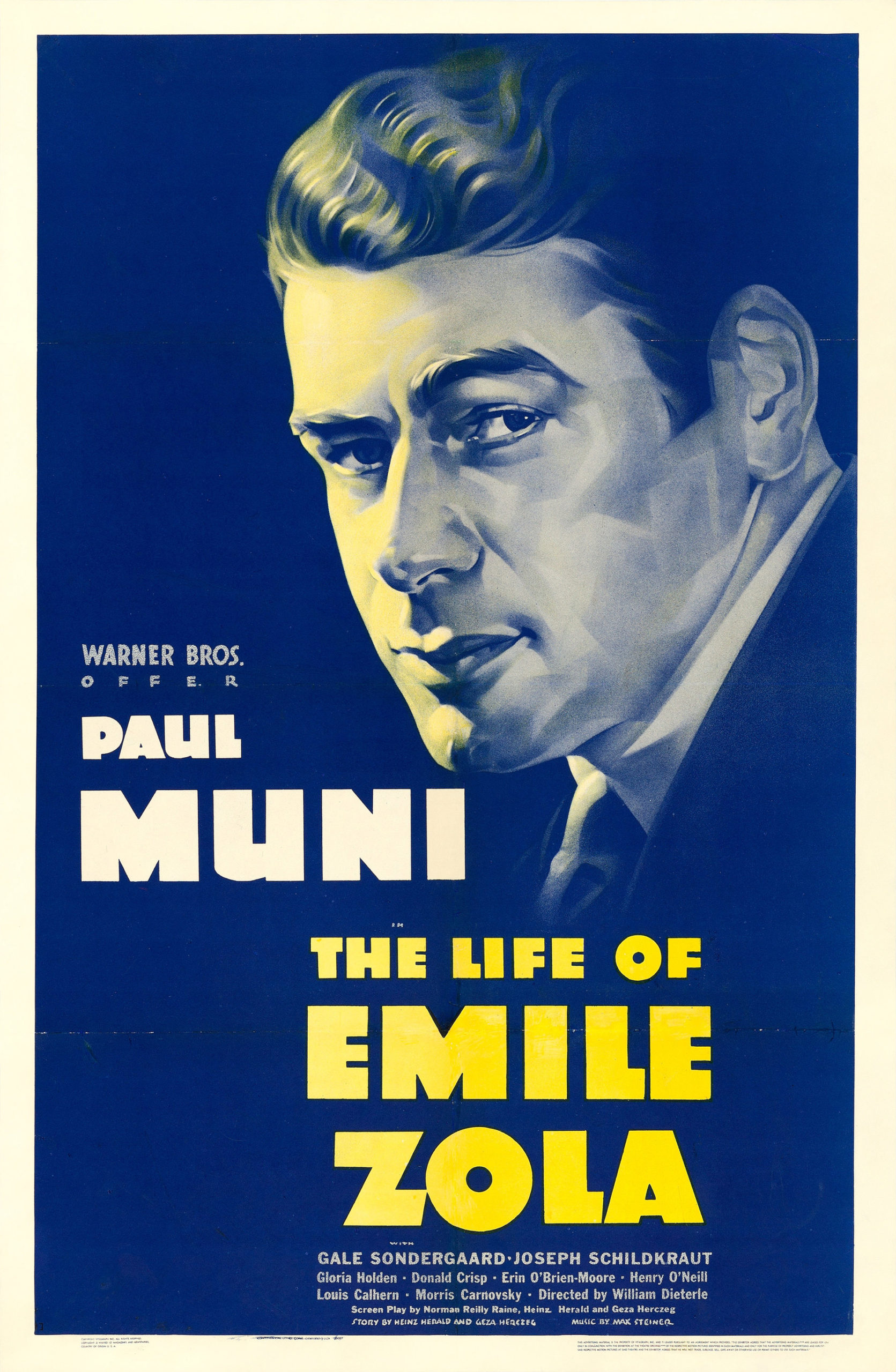

Cinema Scholars presents a retro review for the 1937 Best Picture Oscar-winning biography The Life of Emile Zola. Directed by William Dieterle and starring Paul Muni, Joseph Schildkraut, and Gale Sondergaard.

Introduction

With ninety-five years of Academy Awards history, a few of the Best Picture winners have managed to slip through the cracks of history. While many of the victors are fondly remembered and revered, some winners are well known for their mediocrity or having defeated a cinema classic. Other winners can fall into a gray area with no significant cultural impact.

1937 is by no means a film year with endless masterpieces, but it is also by no means an out-and-out disaster. Without a stellar alternative, the Oscars chose a biopic for their Best Picture of the year. Here we arrive at The Life of Emile Zola.

Synopsis

Paul Muni stars in the titular role; penniless and struggling with his writing as a young man in late 19th century Paris. His writings draw the ire of the French establishment, but a chance encounter with a street sex worker leads to Zola publishing his novel Nana, which gives Zola the success and cultural respect he has been seeking.

With each subsequent writing, Zola gains more attention from the public as well as the censors. Angering the French military and politicians with his novel Downfall, Zola’s riches lead him to a contented existence with his wife Alexandre (Gloria Holden).

Years later, French Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus (Joseph Schildkraut) is falsely convicted of treason and imprisoned. Amid public fervor for the conviction and despite evidence that would vindicate Dreyfus, the French generals decided to suppress the truth to avoid a public rebuke of their judgment. Alfred’s wife Lucie (Gale Sondergaard) pleads with a stagnant Zola to utilize his power and address this miscarriage of justice.

Zola publicly accuses a number of generals and officials in a scathing newspaper editorial. Charged with libel, Zola faces the French High Command and the President of the Republic to vindicate Dreyfus, while also trying to save himself and reinvigorate his passions.

Analysis

Divided into two distinct acts, the first act focuses on Zola’s attempts to bring himself out of poverty through his writing. While living his life, Zola encounters the problems of France, including dangerous mining conditions, a crowded river slum, and a completely ignored suicide.

Living with his equally penniless artist friend Paul Cezanne (Vladimir Sokaloff), Zola’s passions for the betterment of France are hungry. His chance encounter with Nana allows him to view a hidden underbelly of society, which his words expose to the world. All the while, Zola’s morals are clear, and his love of France is foremost in his mind.

Zola is not a dynamic character. At his most poverty-stricken, he is more of an ideal than a person. Railing against the system, Zola wants what’s best for his country and countrymen, no matter what the establishment thinks. Meeting with the chief censor, Zola bluntly demands to be left alone to write how he wishes.

At the film’s conclusion, Zola is more of a saint than a real person. The lasting legacy of the real Zola lies in the films and books based on his life more than his actual writings. The legacy of the Dreyfus affair has lasted well beyond the legacy of Zola.

Dieterle would go on to direct eighty-nine films but never reached the critical or commercial success of The Life of Emile Zola. His directorial style is not one of flash, but patience and room to breathe. In the climactic courtroom scene, Zola finally gets his chance to address the court. Dieterle doesn’t frame Zola against the world, he is in a tight close-up and allows Muni to rouse the crowd with utter righteousness. The less Dieterle does, the more the film sizzles.

The Cast

Muni can’t nail the character down. At times, Zola subtly mutters with righteousness and will shout his objections from the rooftops moments later. Zola’s motives are never in question. He is the physical embodiment of righteousness and the only ones trying to silence him are the ones in the wrong. The only thing truly learned about the man is his stifled passion due to the enormity of his success.

When the primary character is the least interesting part of the film, problems arise. The film actually works on the contrary. Everything related to the Dreyfus affair and the French High Command really sings. In particular, Schildkraut, in his Oscar-winning performance, embodies a deflated sense of decency despite having little to do.

Dreyfus is seen as a good soldier and a good father, but his actions and character are defined by others. All the while, Schildkraut refuses to be a martyr or a victim. His innocence will be proven and he needs only the strength to be patient.

Oscar-winner Sondergaard gives added depth to Mrs. Dreyfuss, in a role that should barely register. Donald Crisp as Zola’s lawyer and Henry O’Neil as the good general of the bunch add to the solid cast of the “good guys.” The less the film focuses on Zola, the better it becomes.

The “villains” of the story are given clear motivations without the mustache-twirling cliches. Each member of the High Command clearly states why they are doing what they are doing. Just like Zola, they aim to protect France and a large part of that involves how the public views the army. If the army makes a mistake, how is the public supposed to trust them when an actual war happens?

Oscar Legacy

The Life of Emile Zola was nominated for a then-record ten Academy Awards at the 1937 Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director for Dieterle, Best Actor for Muni, and Best Supporting Actor for Schildkraut. While Muni (who had won the year before for The Story of Louis Pasteur) would leave empty-handed, Schildkraut and the screenplay won statues.

In Best Picture, the film triumphed over nine others. Of the ten nominees, history has been much kinder to two. The Awful Truth(1937) shot Cary Grant into superstardom and gave the romantic comedy the launching pad into blockbuster territory. Today, the film is a touchstone of slapstick and improvisational comedy.

The film most fondly remembered from 1937 remains the original A Star is Born. Starring Oscar winners Janet Gaynor and Fredric March, the story of film actors on opposite trajectories while also being in love has endured through three subsequent reincarnations.

Conclusion

The Life of Emile Zola hasn’t endured in the cultural consciousness precisely because it falls into that middle ground of quality. It is not bad enough to be infamous, but it isn’t good enough for deification. The most prominent names associated with the film (Muni and Dieterle) have similar legacies as the film.

No one speaks of this film. Even if it’s in a negative connotation, at least you can be memorable enough to inspire passion. The Life of Emile Zola isn’t good enough to rally behind, but it’s also too good to lambast. Maybe that is the film’s true legacy.