Introduction

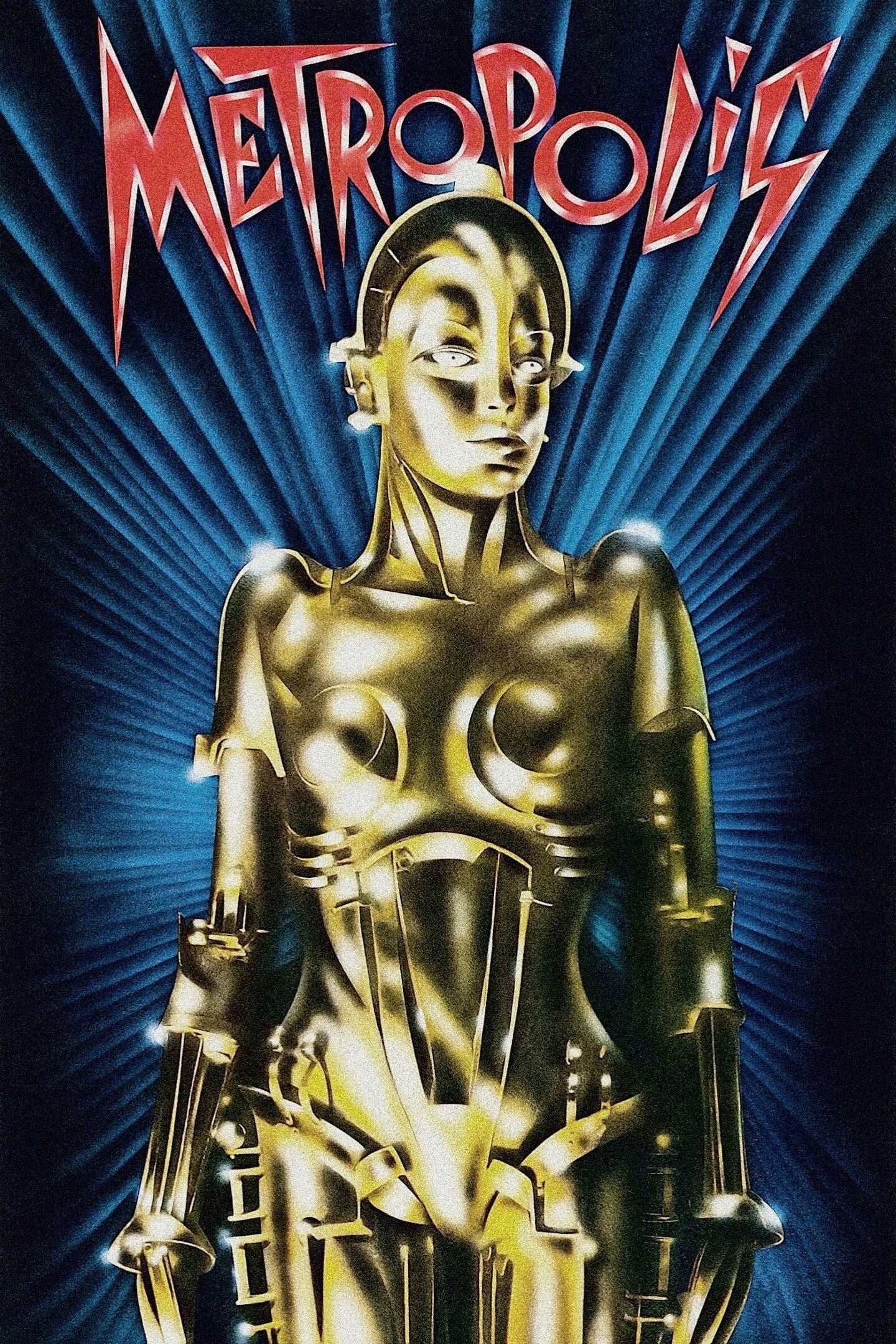

Nearly a hundred years since its premiere, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) remains a source of fascination for generations of filmgoers. Even if you’ve never seen it, you can no doubt recognize the iconic images it has inspired in popular culture around the world. Its bizarre juxtaposition of medieval melodrama with futuristic themes creates a truly unique cinematic experience.

In 2002, Metropolis was the first film admitted by UNESCO into its “Memory of the World Register.” There, it joined the ranks of other historic works of art like Beethoven’s 9th Symphony and the Gutenberg Bible. Simply put, it’s almost unthinkable for anyone seriously interested in film history not to give this movie its due.

German Expressionism

The story behind Metropolis actually begins at the end of the First World War. At the time, German society was having to deal with a collapse of the social order, rampant inflation, and the humiliation of having lost the war. This helped create a public mood that reflected a deeply pessimistic outlook on life.

It was in this setting that a new artistic movement took hold and began to thrive. It was called Expressionism, and typically featured bizarre characterizations set against unnatural backgrounds. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922) were early classics of this style of cinema.

At the time, there was a young director who was starting to make a name for himself in the German film industry. His name was Fritz Lang. Working at a breakneck pace during the early years of the Weimar Republic, Lang turned out dozens of films in a range of genres.

And as his expertise and reputation grew, he gradually moved onto more substantial fare. Films like Destiny (1921), Spiders (1919), Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), a two-part spy drama, and Die Nibelungen (1922), a two-part retelling of the legend of Siegfried, were all huge hits. Together, they helped the German film industry solidify its international reputation.

Fritz Lang, the Taskmaster

Possessing an aristocratic personality, Lang soon became known for driving his actors and crew to their breaking points. He rarely showed regard for people’s feelings. Once, Lang even deliberately threw an actor down the stairs to make him look disheveled. He thought the actor’s confused look of pain would appear more real in front of the camera.

The director also carried a riding crop on the set, which he used to slap his thigh whenever anything displeased him. Wearing his ever-present monocle, he looked and acted every bit the part of a merciless taskmaster. Nevertheless, following his string of successes, in the mid-1920s, Lang was basically given a free hand to undertake any project he wanted.

A Voyage to America

While sailing on a steamship across the Atlantic to attend the American premiere of Die Nibelungen, Lang was taken aback when he entered New York harbor. There, he was confronted by the sight of a seemingly endless series of skyscrapers. He later stated:

“…The buildings seemed like a vertical curtain, shimmering and weightless – an opulent staged backdrop set against a sinister sky – in order to dazzle, divert, and hypnotize…”

For someone raised in the ancient cities of Europe, it must have been quite a sight. Lang then traveled on to Hollywood, where he was given a tour of MGM studios. He was amazed at the assembly line system of production he saw there. It seemed to him that MGM could turn out high-quality, big-budgeted features almost at will.

The Production of Metropolis

Lang now knew what he wanted his next project to be. An enormous film that would outdo anything Hollywood had yet produced. Called Metropolis, it would be an ambitious production about a city set one hundred years in the future. Further, it would employ the latest film technology available in Germany at the time.

The production would utilize over thirty-six thousand extras and two hundred thousand costumes. However, with an initial budget of 1.5 million Reichsmarks, it wasn’t initially supposed to be the most expensive film in the world. Not yet anyway.

Filming on Metropolis began in May 1925 and lasted until August 1926. This was an enormous time span, given the fact that most films of that era were shot over a couple of weeks. The production required the construction of enormous sets, along with dozens of miniature models and matte paintings. Together, they would be used to create the illusion of a living, breathing city in the 21st Century.

Visual Marvels

Towering skyscrapers, moving cars on elevated freeways, streets depicted as deep ravines, night shots with rotating lights, underground housing complexes, a huge stadium, teleconferencing systems, high-tech laboratories, and avant-garde buildings…these were just some of the visuals that Lang’s creative team went about fabricating.

A lot of this was painstaking work. To mimic the traffic patterns of a real city, over three hundred miniature-model cars were created. Using stop motion techniques, over a dozen technicians had to move each one a few millimeters at a time for every frame of film exposed. Eight full days of work were needed to create a mere ten seconds of film.

To create the illusion of an actual crowd running across a skywalk, a model city was built, whose reflection was captured in a mirror. A camera would then shoot the mirror, with key spots in its surface cut away. Live images of dozens of people running a hundred yards away would then fit neatly onto the walkway.

“How Did They Do That?”

It’s important to remember that filmmakers of the 1920s didn’t have access to things like optical printers. They weren’t able to do dissolves or layer images after the fact. All the effects they created were done live in the camera.

This meant they had to manually roll the film back into the camera to create multiple exposures. But if they goofed, or misjudged the exposure setting…well, there went days, or sometimes weeks, worth of work.

Knowing the extraordinary amount of pre-planning and sheer sweat necessary for creating the iconic images of Metropolis makes them even more impressive today. It’s the film equivalent of viewing an ancient temple built thousands of years ago and wondering, “How did they do that?”

It Was No “Picnic”

Of course, true to form, Lang didn’t cut his actors any slack during the filming. Brigette Helm, who at the age of nineteen played the movie’s heroine Maria, described the working conditions in Metropolis this way:

“I can’t forget the incredible strain they put us under. The work wasn’t easy…For instance, it wasn’t fun at all when Grot drags me by the hair to have me burned at the stake. Once I even fainted, during the [robot] transformation scene…because the shot took so long, I didn’t get enough air.”

For other sequences, Lang made five hundred schoolchildren work for two weeks straight, standing in pools of cold water. He even threw some extras into the path of powerful water jets for the flooding sequences in the film. Gustav Frohlich, who played the lead role of Freder, later recalled that:

“Working under the directing hand of Fritz Lang wasn’t a picnic for anyone.”

Lang’s insistence on perfection drove the crew to their absolute limits. When they finally finished, the production had exposed nearly two million feet of film. The costs of Metropolis had also come in at four times what had been originally budgeted.

Metropolis Premieres

Final editing was performed during the fall of 1926, and on January 10th, 1927, Metropolis had its gala premiere in Berlin. An estimated fifteen thousand people saw it over the first few weeks. The original run time clocked in at about two and a half hours.

Audiences at the time didn’t know what to make of what they saw. The film is definitely an odd mix of science fiction, trite melodrama, simplistic moralizing, 1920s idealism, social commentary, and plain old kitsch. It’s technically impressive, but the story is heavy on allegory and symbolism. Most agreed with Luis Buñuel, who had this to say:

“The story in the film was trivial, bombastic, pedantic, and of an antiquated romanticism…”

While also calling it:

“…the most marvelous picture book imaginable.”

A Major Flop

Initially, Metropolis only earned back seventy-five thousand Reichsmarks out of its final estimated six million dollar budget. It was chalked up as a major flop and drove the studio, which had financed it, perilously close to bankruptcy.

However, in many ways, the journey of Metropolis was only just beginning. Even before the film was finished, UFA had signed a major distribution deal with Paramount Pictures in the United States. They shipped one of their three negatives to Hollywood, where it was screened for studio executives.

Paramount thought the narrative was problematic and undertook the task of cutting it down to make it more “commercial.” All told, they took out around thirty minutes of the story, leaving it even more disjointed and harder to follow than before. The excised footage was subsequently destroyed.

Scattered to the Four Winds

Against Lang’s protestations, the two remaining negatives of Metropolis in Germany were also edited down along the same lines. Copies were sent to Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, with each country making its own cuts. A ninety-minute version of the film was shipped to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, from which most subsequent prints were made.

To further confuse things, at the end of World War II, the Russians confiscated all the remaining clips of the film that had remained in German possession and took them back to Moscow. The Russians had banned the film in their own country back in 1929.

Metropolis was considered a total failure, and the various copies of the film had been scattered to the four winds. All three of its original negatives had been destroyed. And no one gave a second thought to preserving the pieces that remained.

Fickle Politics

As for Lang, he recovered from the failure of Metropolis and continued to make other successful films in Germany. They included Woman in the Moon (1929), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), and M (1931), his first talking production.

However, the door to Germany’s film renaissance was closing fast. The Nazis came to power in early 1933, and within the first few months, propaganda chief Josef Goebbels banned several of Lang’s films for promoting anti-authoritarian values.

The director thought he was persona non grata with the new regime. But then, he was positively shocked when Goebbels subsequently offered him the job as head of the German film industry. Apparently, Adolf Hitler was a big fan of Lang and had reportedly been very impressed by Metropolis.

Subsequently, Lang informed Goebbels that he needed time to think about his generous offer. However, what the Nazis didn’t know was that Lang held a secret: he was half-Jewish on his mother’s side.

Lang Leaves for Hollywood

The very day that Goebbels offered him the job, Lang boarded a train to Paris and left Germany. After living in France for nine months, he emigrated to the United States, where he settled into a long and successful career in Hollywood.

There, he directed twenty-one films over the next few decades. These included such classics as Fury (1936), The Big Heat (1953), Moonfleet (1955), and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956). As he aged, Lang became more mellow. He later confessed:

“To begin with, I should say that I am a visual person. I experience with my eyes and never, or only rarely, with my ears – to my constant regret.”

Lang died in 1976, but before he passed away, he no doubt became aware of the resurrection of one of his greatest films. As more and more people saw clips of the striking visuals from Metropolis, rumors began to circulate that there were more complete prints floating around besides the ninety-minute version housed at MOMA.

Enter Giorgio Moroder

One day, during the early 1980s, Oscar-winning composer Giorgio Moroder (Midnight Express, Flashdance, Top Gun, Scarface) happened to be at home and playing some music in the background while Metropolis aired on television.

He was suddenly struck by how effortlessly the music seemed to match up with the visuals. A strange idea suddenly occurred to him: how it might be fun to sponsor a restoration of the film and score it with an original contemporary soundtrack.

It was an audacious and intriguing concept. What Moroder was attempting to do was create a music video out of a pre-existing work. He gathered every missing scene of Metropolis he could find, tinted the film, added sound effects, and replaced the title cards with subtitles. Moroder then wrote a new score and hired musical icons from the 1980s like Bonnie Tyler, Adam Ant, Freddie Mercury, and Loverboy to perform the songs that he had created just for the film.

The final result split opinions right down the middle. Some applauded Moroder’s attempts to introduce the movie to a new generation while promoting film preservation at the same time. On the other hand, some felt Moroder had desecrated an important work of art. As one critic jokingly pointed out, the music is more dated than the film.

Metropolis: The “Holy Grail” of Lost Films

If nothing else, Moroder’s efforts spurred other film preservationists to try to reassemble a complete version of this “holy grail” of lost films. Back in Munich, the Germans started to collect every fragment of Metropolis that they could find. Using the original musical cues from 1927, they put them back where they belonged according to the film’s original timeline.

As part of this effort, the Germans reached out to the Russians and asked them to return the materials they had stolen in 1946. Somewhat surprisingly, not only did the Russians agree to do this, but astonished the Germans by telling them that for decades the Soviets had been trying to reassemble their own version of the movie behind the Iron Curtain. It seemed that American and German audiences weren’t the only ones fascinated by this particular film.

Metropolis Reborn

It wasn’t until 1998 that a final, definitive restored copy of Metropolis was produced using the latest in digital technology. Building on the work started in Munich and following an exhaustive around-the-world search, a team of film historians and preservationists was able to piece together a new version of the film. It was like putting together a giant jigsaw puzzle.

The project took them three years and was heralded as the most complete copy of Metropolis in existence. It premiered at the Berlin Film Festival in front of huge crowds in February 2001 and was released theatrically. The DVD was also a best seller. However, at a running time of just over two hours, it was still approximately 25 minutes shorter than the premiere version.

An Old Story…

The final resurrection of Metropolis wasn’t done just yet. Back in the mid-1980s, one of the curators at an Argentinian film archive in Buenos Aires was going over his collection when an elderly caretaker told him how he would never forget the time they screened the film back in 1959. He told him that the projector was broken, and he had to stand there for two and a half hours holding his finger over the film gate so an audience could watch the entire picture.

After the 2001 premiere, the curator remembered that story and wondered if the caretaker had been exaggerating when he came up with the time figure of two and a half hours…since that would make it roughly the same length as the original version.

He asked, and received, permission to do an exhaustive search of the film archives to see if they had any copies of Metropolis in their possession. Then, after months of searching, he found it. A badly deteriorated 16mm COMPLETE print of the original film. Apparently, a “bootleg” copy had been made right after the 1927 premiere so that it could be screened for potential exhibitors in Argentina. Then, it was subsequently forgotten about. It was like finding a hoard of buried treasure.

The “Complete” Version

Despite all the hoopla surrounding the most recent find in Argentina, the sad fact is that the new materials that made up the complete print of Metropolis left a lot to be desired. It was a third-generation print that had been rotting in a film can for nearly forty years.

As a result, all the new footage was considerably marred by artifacts and image deterioration. They were cleaned up as much as possible using digital transfer technology. But when the source is compromised, there’s only so much one can do.

Still, the find generated another huge groundswell of interest. The final “complete” version of Metropolis premiered again on February 12, 2010, in Berlin. Sixteen hundred people filled the Friedrichstadt-Palast, while more than two thousand sat in the snow beneath an enormous screen erected at the Brandenburg Gate.

Simultaneously, another screening was held in Frankfurt, while the performance was broadcast live across the rest of Germany. Turner Classic Movies also made the new restoration the centerpiece attraction at their film festival in Hollywood later that same year.

The Fascination With Metropolis

After all these years, it would seem that Metropolis still manages to fascinate and enthrall filmgoers. Examples of its influence can be seen in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), where the central tower in the opening scenes was directly modeled after the one in Lang’s film.

Also, if you ever catch Madonna’s music video “Express Yourself,” you’ll notice the entire visual design is lifted straight from Metropolis as well. In a homage to Lang, you can even see her wearing a monocle around her neck. That video was directed by David Fincher, who went on to the big time with feature productions such as Fight Club (1999), Seven (1995), Zodiac (2007), and The Social Network (2010).

For our money, Metropolis remains one of the most ambitious and entertaining of all silent movies. A marvel to watch, its astonishing visuals still make it essential viewing for anyone interested in film history. Because if nothing else, they served as a preview for the countless other cinematic wonders that were yet to come.