Introduction

During the 1930s and 1940s, Busby Berkeley was a household name. When it came to musicals and elaborate dance numbers, his films were often described as the ultimate expression of Hollywood glitz and glamour. Throughout film history, there have been very few – if any choreographers who can lay claim to Berkeley’s fame as a visual stylist and auteur.

When you bought your ticket to one of Berkeley’s films during the Great Depression, you didn’t care who the stars were. Nor, who directed the picture, or even what the story was about. You only knew that something visually dazzling awaited you once entered the theater, and that film projector flickered to life.

The sequences Berkeley created showcased some of the most visually intoxicating sequences ever put on celluloid. Well before the advent of CGI, they remain “special effects” in their own right. To this day, they still retain the power to leave the viewer awestruck at their complexity and ingenuity.

Yet, even though Berkeley was recognized as a legitimate genius, he, like many creative types, fought more than his fair share of personal demons. As a result, his story serves as yet another example of the fine line that often separates brilliance from insanity.

Beginnings

Busby Berkeley was born in Los Angeles in 1895. His real name was William, but his parents nicknamed him “Busby” after Amy Busby. Amy was a popular star on Broadway at the time. A certified “mama’s boy,” Busby was inseparable from his mother. After he matured, she continued to live with him throughout most of his adult life. This included four of his six marriages.

As a teenager, Berkeley attended a military academy in upstate New York. He soon found himself serving in a field artillery unit during World War I. The young man realized that he enjoyed the structure and precision that military life offered.

After the war ended, he continued to serve as a conductor for U.S. Army parades and stage shows. There, he discovered he had a talent for visually organizing marching units. He was soon directing battalions of over 5,000 men, in maneuvers of ever-increasing size and complexity.

After Berkeley left the armed services, he didn’t have many job prospects lined up. As a result, he went to Broadway, to try his hand on the stage. While Berkeley struck out as an actor, he quickly earned a name for himself. This was done by demonstrating an ability to organize chorus lines.

Berkeley had never aspired to a career in choreography. However, it seemed all those years of taking part in army drills had left him with a prodigious talent. One which had nothing to do with the military.

Soon, word reached Hollywood, and movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn offered Berkeley a contract to come to Tinseltown. He was to assist with several films that featured singing and dancing sequences. It was the dawn of sound in the film industry, and musical numbers were all the rage.

42nd Street

In 1933, Warner Brothers were making a picture called 42nd Street. By that time, studio head Jack Warner thought the public was getting sick of the same old song and dance acts in the movies. He nixed all the musical numbers planned for the film.

To thwart this move, producer Darryl F. Zanuck hired Berkeley to do the choreography but had him shoot all the sequences in the evening when the studio heads weren’t around. Zanuck then tacked all the musical numbers onto the end of the film and presented the final result to Warner.

The results were nothing short of revolutionary. One of the original backstage dramas, 42nd Street features three incredible numbers: “Shuffle Off To Buffalo,” “I’m Young and Healthy,” and the title sequence. Altogether, they last nearly twenty minutes.

Up until then, film musicals had pretty much treated the movie audience as if they were attending a Broadway show. One in which a stationary camera stayed “in its seat,” so to speak. Most often, a fixed lens was used to capture a routine that took place on a confined stage.

However, even in these early years of cinema, Berkeley instantly recognized the power of the moving camera. His shots would track and follow the motions of the dancers. Often, they would even fly around and over them. It was stunning and unheard of.

Breaking New Ground

Even more groundbreaking was Berkeley’s displacement of time and space. One of his typical dance routines might start on a regular stage. Then quickly undergo a metamorphosis during which the audience is whisked away into a fantasy world, within which the normal rules of gravity and logic don’t apply. Only to be deposited back after the number in front of the “real-world” audience, which was busy clapping and roaring its approval on screen.

In addition to contributing one of Film History’s most famous lines: “…you’re going out there a youngster, but you’ve got to come back a star!!..” 42nd Street became one of 1933’s biggest moneymakers. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture and made Busby Berkeley one of the most sought-after talents in the movie industry. It also saved Warner Brothers from impending bankruptcy during the Depression.

Innovations

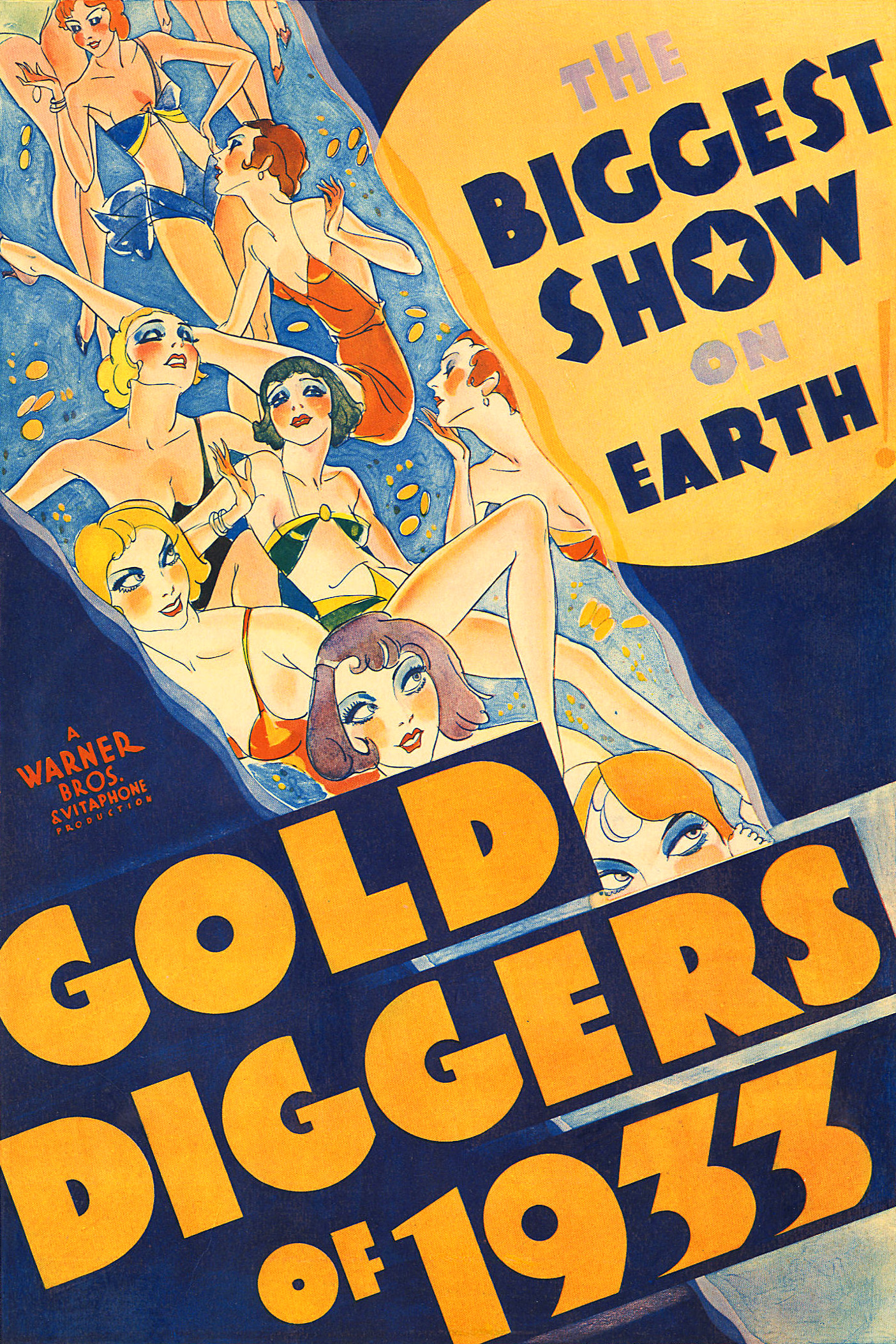

More Busby Berkeley films quickly followed: Gold Diggers of 1933, Footlight Parade, Roman Scandals, Fashions of 1934, Wonderbar, Dames, Gold Diggers of 1935, and In Caliente. The films were so popular with the movie-going public that Berkeley was given complete artistic control over the musical numbers he created. With that power, he began to push both himself and the film technology that was available at the time.

In the process, Berkeley gave life to a new art form that had never previously existed on such a grand scale. Some of Berkeley’s visions were so elaborate, that Warner Brothers were forced to build one of the largest sound stages ever constructed. This was just to film these elaborate musical numbers.

One of the innovations for which Busby Berkeley became known was the “Berkeley Top Shot.” This consisted of a camera that was placed high overhead, shooting directly down at the stage floor at a 90-degree angle.

There, the dancers would act out intricately choreographed routines, moving their arms, legs, and various props in unison. These movements created complex, living, and ever-changing geometric shapes on the screen. The entire effect was akin to watching some bizarre organic entity through a giant kaleidoscope.

If he couldn’t get the distance he wanted, Berkeley wasn’t averse to going through the roof of the studio. On at least one occasion, he had a hole cut through the ceiling so that the cameraman could get the shot he wanted from outside the confines of the building.

Technique

Conversely, Busby Berkeley was also a big fan of close-up shots and wanted to direct the dance numbers himself. He would often convince producer Samuel Goldwyn to let him. He would use only one camera and never used more in his films. Also, regarding showing close-ups of the chorus girls, he stated:

“We’ve got all these beautiful girls in the picture…Why not let the audience see them?”

Again, the ultimate effect was to create the illusion that viewers were up on stage with the dancers, and not just passive members of the audience. It was another mashup featuring the techniques of both the cinema and army drill formations.

Further evidence of Berkeley’s genius came from his working methods. As elaborate as his stagings were, many were shot in single takes using multiple cameras. But this was only possible because every detail was planned out and rehearsed well in advance.

Berkeley would spend hours – sometimes days – just sitting or walking around these immense sets. He would put all of the pieces together in his mind, while the rest of the cast and crew would sit around and watch.

This drove many of the studio producers crazy. However, once Berkeley had everything straight in his head, he would organize the execution of the sequence with the disposition (and some claimed the demeanor) of a drill sergeant.

Knowing this, and watching the final results on film, it’s positively astounding to contemplate the imagination and mental gymnastics that must have taken place in the man’s mind as part of his thought processes.

Evidence of Genius

Gold Diggers of 1935 contains two of Berkeley’s most memorable sequences. “The Words Are in My Heart” features fifty-six beautiful girls wearing luxurious long white dresses while they sit and play fifty-six separate baby grand pianos.

Set on a shiny, black floor, the pianos appear to float on air as they come together to form a single rectangular platform upon which a single dancer pirouettes. As the camera pulls back, she almost assumes the likeness of a tiny ballerina dancing inside a miniature music box. It’s an astounding illusion. All the more remarkable for the fact that there are no optical effects involved.

In the same film, “The Lullaby of Broadway” the number lasts over thirteen minutes and is one of Berkeley’s most famous creations. Featuring over one hundred and fifty chorus boys and girls doing a perfectly synchronized tap dance routine, it’s a dreamlike film within a film and chronicles the daily routine of a Broadway “Babe” who sleeps all day and parties all night.

As the Broadway Babe endlessly travels from club to club, she encounters other revelers who inhabit the same nocturnal world as she. That is until, quite unexpectedly, she’s pushed off a balcony and tragically falls to her death.

The Creative Process

None of these amazing sequences was easy to create. As one of his personal goals, Berkeley strove never to repeat any of his past accomplishments. His aim was always to try and top himself. This approach, combined with constant demands from the studio brass combined to make Berkeley’s life a living pressure cooker. He drank heavily and regularly worked until the wee hours of the morning.

Many of Berkeley’s musical numbers featured water. This is because he found that one of the few things that would help him relax was to sit in a bathtub for hours. All the while drinking endless martinis. He claimed that this was the only way he could come up with new ideas. The cast and crew were more than slightly annoyed by his habit of drunkenly calling them up at 3 am, with instructions for setting up a new routine.

On Trial

Tragedy struck in 1935 while Berkeley was at the height of his fame. After attending a party, celebrating the completion of his latest film, Berkeley was driving home along the Pacific Coast Highway, possibly inebriated. Suddenly, he lost control of his car and careened to the wrong side of the road. He side-swiped a car, and plowed into another, killing three people. Berkeley was arrested and charged with second-degree murder.

During the resulting trial, Berkeley had to be brought into court on a stretcher. Suffering from head and leg injuries, he was unable to stand. For their part, Warner Brothers had their own set of problems. The public still had a huge appetite for Berkeley’s pictures, and they had him scheduled to work on three more movies back to back.

They waited for Berkeley to be able to walk. Then, they immediately shifted the production schedule to evenings. This meant that Berkeley had to sit in a courtroom all day, then go to work each night, usually until 3 or 4 am, for months on end. For his part, Berkeley agreed to this inhumane schedule because he felt he needed to work to assuage his guilt.

Warner Brothers got many of their employees at the party to testify at the trial. This was done on Berkeley’s behalf. Despite much evidence to the contrary, several “stars” went on the record to state that he wasn’t drunk when he got into his car.

This would have been completely out of character given Berkeley’s previously documented behavior. Probably, as a result of this testimony, the trial ended in a hung jury. As did a second one. During a third trial, however, Berkeley was finally acquitted.

Out of Control

Berkeley’s life continued to spin out of control. He married and remarried multiple times. His behavior on set also continued to be erratic. At least one actress claimed he almost got her killed. This was while filming one ambitious sequence as part of a film. While working on the movie Girl Crazy (1943) with Judy Garland, the equally temperamental actress got him fired. This was for making her unnecessarily shoot dance scenes multiple times.

Throughout this downward spiral, Berkeley had two constants in his life. The bottle, and the affections of his mother. In 1946, the latter succumbed to cancer after a long illness. It was the final straw. The mental breakdown that Berkeley had kept at bay for several years finally manifested itself with a vengeance.

A few weeks after his mother’s death, Berkeley tried to kill himself by slitting his throat and wrists. A servant found him lying on his bathroom floor in a pool of blood. Acting quickly, the houseboy bound up Berkeley’s wounds, called an ambulance and almost certainly saved his life. When he recovered from surgery, Berkeley told a friend:

“…I’m a has-been and I know it…I can’t seem to get myself straightened out for any length of time….I’m broke…when my mother died, everything seemed to go with her…”

Rock Bottom

Even this painful admission didn’t signify that Berkeley had hit rock bottom. After recovering from his wounds, Berkeley was admitted to the psychiatric ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. There, he would spend the next six weeks. Later, this is how he described the experience:

“…It was a nightmare…I was thrown in with dirty, disheveled, bedraggled creatures. They were so short of space, my cot was placed in the corridor, where these horrible characters passed me day and night…I knew that if I wasn’t already mad, I soon would be…”

Comeback

When Berkeley was finally released, his weight had dropped from 170 to 107 pounds. He only had $650 to call his own. His name recognition was still worth something, however. After proving he could still handle directing chores, Berkeley gradually found steady employment. He created water ballet sequences for a series of successful films starring MGM’s Esther Williams.

These included the huge hits Million Dollar Mermaid (1952) and Easy to Love (1953). Some film historians feel this later work deserves as much praise as what Berkeley was able to accomplish during his heyday with Warner Brothers.

Berkeley’s real comeback would come in the 1960s. Television had introduced a whole new generation to his work. As a result, several retrospectives were created at various film festivals, dedicated to his work.

Books were written about Berkely’s movies and colorful life. Suddenly, he found himself in demand for various interviews, lectures, and talk shows. At long last, people acclaimed him as the genius he almost certainly was.

A New Audience

Of course, there was another underrated element behind Berkeley’s resurgence in the 60s. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the newfound interest in his work came at the same time that certain illegal substances were becoming more widely used throughout society.

Simply put, many college students found that Busby Berkeley musical numbers were ideal visual accompaniments for getting high. Or, were great to view while experimenting with various hallucinogens.

Suffice to say, a lot of the young people who flocked to Busby Berkeley retrospectives weren’t necessarily interested in his camera techniques. They probably couldn’t even tell you anything about the film’s plot, after they floated out of the theater.

Busby Berkeley passed away from natural causes in 1976 at the age of 80. Throughout his long career, he carried with him a deep, dark secret…No one had ever taught the former drill instructor how to dance.