Introduction

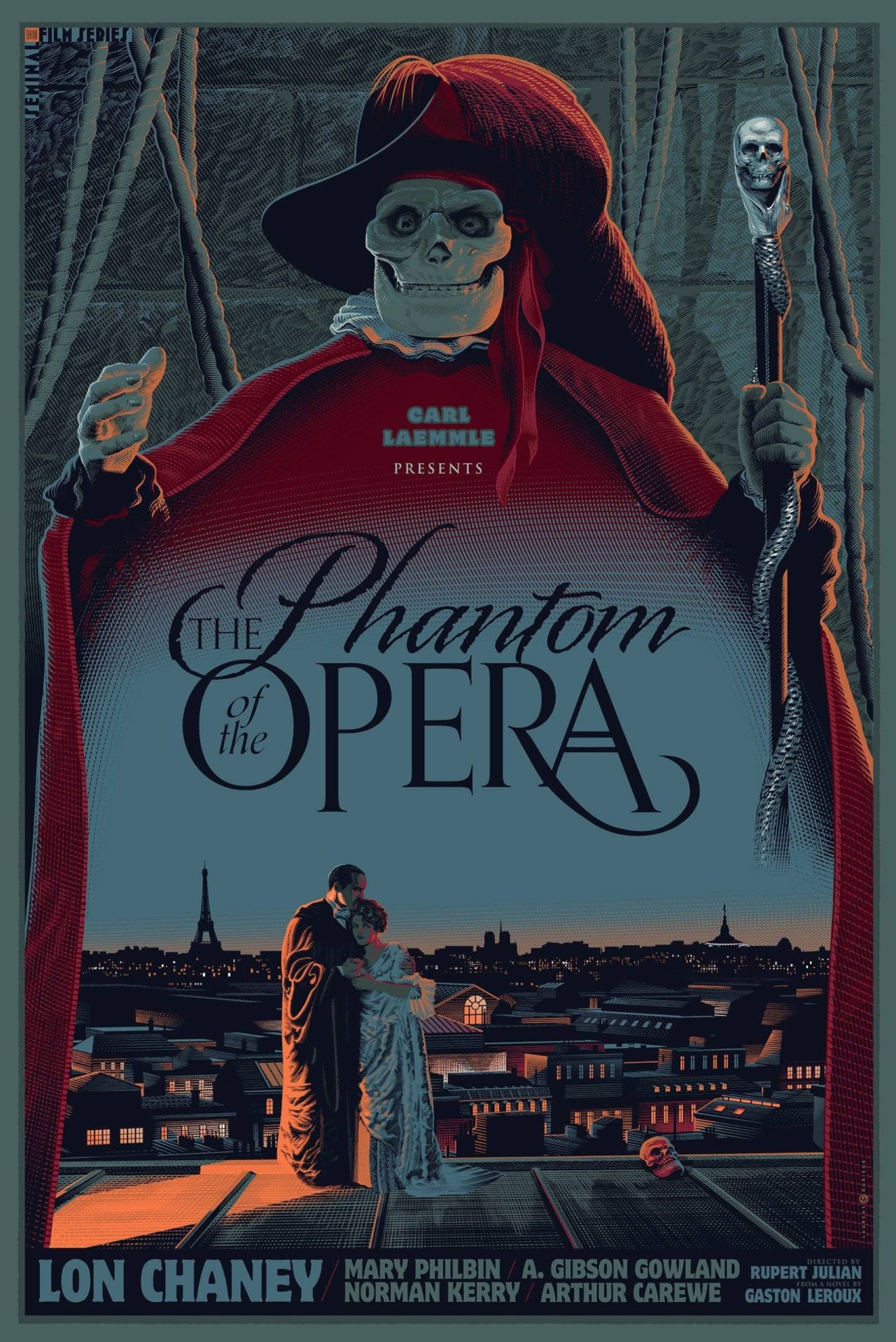

Universal Studios has been synonymous with high-quality horror movies for almost its entire existence. Although 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame could be considered the first movie in this genre for the studio, it really kicked off two years later with The Phantom of the Opera.

The idea for the movie received its genesis when Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal Pictures, took a family vacation in Paris in 1922. After a chance encounter with author Gaston Leroux, their conversation took an interesting turn when the subject of the Paris Opera House came up. Laemmle was an admirer, and Leroux gave him a copy of his book Le Fantôme de l’Opéra, published in 1910.

Laemmle bought the rights the following day, after devouring every word written between the covers the night before. This would be a star vehicle for Lon Chaney, and was added to the shooting schedule for 1924.

Art Direction

To get the look of the Paris Opera House correct down to that last detail, Laemmle hired French art director Ben Carré, who had worked at the Opera House for several years. During pre-production, Carré drew 24 charcoal sketches. These drawings were used as the basis to build the sets, including the subterranean levels, which were not based on fact but imagination.

A substantial portion of the budget was poured into the creation of the Paris Opera House sets. They were built on Soundstage 28 at the Universal Lot. These Opera House sets were so lavishly detailed that they were not dismantled and removed from the building until its demolition on September 23, 2014.

The “Phantom’s” Design and Makeup

Like in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Chaney was given complete control over the design and application of the makeup for Erik aka The Phantom. Chaney based his character’s appearance on an illustration from the novel by Andre Castaigne.

To achieve the desired look, Chaney stuffed cotton balls into his mouth to raise the contours of his cheekbones and crafted a nose made out of modeling putty reinforced by wires to give the nostrils the turned-up look they had in the film. With the exception of a skull cap and a pair of false teeth, the rest of the transformation was done entirely with makeup.

“In The Phantom of the Opera, people exclaimed at my weird make-up. I achieved the Death’s head of that role without wearing a mask. It was the use of paints in the right shades and the right places—not the obvious parts of the face—which gave the complete illusion of horror…It’s all a matter of combining paints and lights to form the right illusion.”

– Lon Chaney

Screenplay

The screenplay for The Phantom of the Opera was written by Elliot J. Clawson, who had worked with the film’s director Rupert Julian for nearly ten years. Clawson relied heavily on the novel to create the screenplay. Almost the entire novel was contained in the script and nearly all of it was filmed. However, some sequences did not make it into the movie because of the lengthy runtime.

The ending was changed four times under the direction of Laemmle during this phase. Also, the choice was made to go with an ending where the Phantom dies in the home of Christine (Mary Philbin), with whom he was obsessed.

Production

Shooting on The Phantom of the Opera began in October, 1924 with Chaney’s scenes being amongst the first to be filmed. The majority of the cast and crew didn’t care for Julian’s attitude on the set and filming was tense, with Chaney essentially ignoring his direction and playing the role how he wanted.

One of the aspects of the production that left a lasting impact was the decision to shoot seventeen minutes in Process 2 Technicolor. Of the scenes shot in Technicolor, only the “Bal Masque” scene survives.

When the movie was fully assembled it was shown as a sneak preview to audiences on two separate days – January 7 and 26, 1925 in Los Angeles. This was basically a precursor to the focus groups that we have today. Audiences at these screenings hated it, especially the ending and left comments such as:

“…There’s too much spook melodrama. Put in some gags to relieve the tension…”

The official release was canceled and Julian was fired. Edward Sedgwick was hired by Laemlle to reshoot a significant portion of the movie with a new script by Raymond L. Schrock and Elliot Clawson, which was more comedic in tone.

On April 26, 1925, a preview was held of this new comedic cut of The Phantom of the Opera, this time in San Francisco. This preview went even worse than those for the previous version. A riot nearly broke out as the movie was met with boos and things being thrown at the screen.

A third cut of the movie was then assembled using primarily the original footage shot by Julian. The only thing left from the Sedgwick version was the ending with the Phantom drowning in the Seine.

Release and Legacy

The Phantom of the Opera premiered in New York City on September 6, 1925, and in Hollywood on October 17, 1925, to lukewarm reviews. The critics had praised the makeup work by Chaney, as well as the elaborate sets, but were critical of the acting performances in the movie.

The films legacy has improved greatly over the years and is considered a true classic by modern audiences, who have actually never seen the 1925 version. All the negatives of that version were melted in 1948 for the silver content contained in the nitrate film. In the 1930s, 16mm prints were made of the 1925 version for home use, but they were of poor quality, and missing several scenes.

The version that audiences predominantly experience since then is based on a 1929 sound re-release. This contains footage from a second camera set up during filming, which was re-edited in 1952 to create the “George Eastman House” version. This is typically the version of The Phantom of the Opera experienced today. This version is 20 minutes shorter, and contains at least 40% different footage than the original. How, why and by whom this version was created remains a mystery to this day.