Introduction

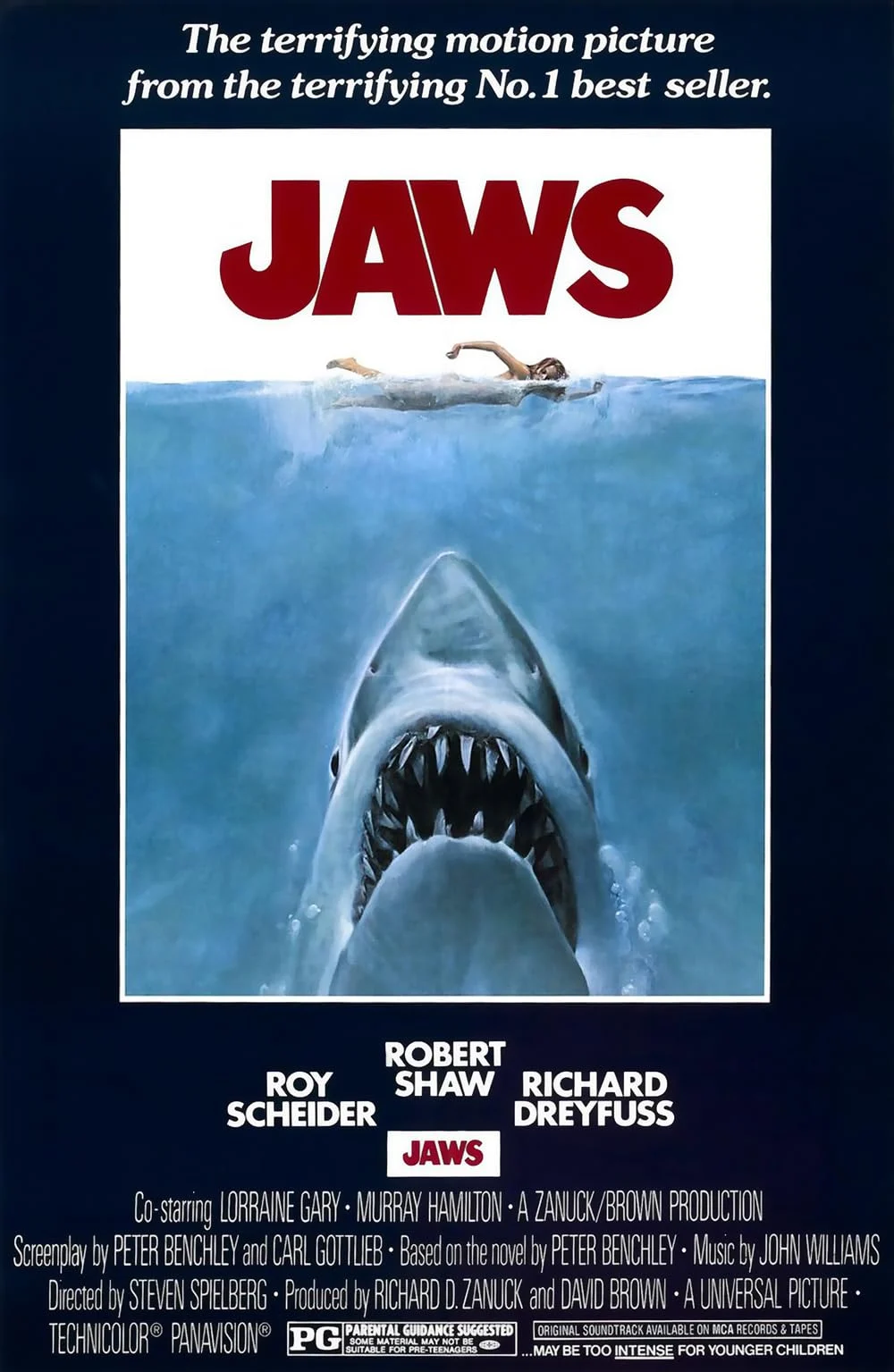

Half a century ago, a great white shark chomped its way into the cultural zeitgeist, forever reshaping the landscape of American cinema. Cinema Scholars celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of Jaws, a film that instilled an enduring fear of the ocean and gave birth to the summer blockbuster. The film remains a beloved classic. While the people behind it have aged and passed this mortal coil, the film’s legacy and sheer brilliance continue to be passed on from generation to generation. This is the tale of how a man-eating shark became a cinematic icon that changed Hollywood forever.

Beginnings

In the early 1970s, Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, producers at Universal Pictures, were “exploring” new projects intended to capture audience interest. One of the promising properties was Jaws, a novel by Peter Benchley that had generated significant buzz. Brown had first read about it in the literature section of Cosmopolitan magazine, then edited by his wife, Helen Gurley Brown.

Benchley, a journalist and former presidential speechwriter, had tried writing fiction in the early 1970s. His novel Jaws, published in 1974, became an almost overnight bestseller. The story focuses on a small coastal town threatened by a great white shark. Ironically, Benchley would advocate for shark conservation as he became concerned about the story’s unintended consequences on the public’s perception of sharks.

Zanuck and Brown saw the potential for a thrilling feature film. This, despite the logistical challenges of creating a convincing mechanical shark. That challenge would eventually become one of the defining aspects of the film’s production. Both Zanuck and Brown read the novel in one sitting and quickly purchased the rights. They told anyone that would listen that it was “the most exciting thing that they had ever read.”

Spielberg’s Big Break

Not even thirty years old, Steven Spielberg was still a relatively unknown talent when he was selected to direct Jaws. Up to this point, he had been known for his excellent TV film Duel (1971). His first feature film came three years later with The Sugarland Express (1974), starring Goldie Hawn and William Atherton. However, the film was not a commercial success, which Spielberg blamed on poor marketing by Universal Pictures. Still, the film earned raves at the Cannes Film Festival, and legendary New York Times critic Pauline Kael stated:

“Spielberg uses his gifts in a very free-and-easy, American way—for humor, and for a physical response to action. He could be that rarity among directors, a born entertainer—perhaps a new generation’s Howard Hawks”

Spielberg was not Zanuck and Brown’s first choice to direct Jaws. They had initially approached John Sturges, who had directed the critically acclaimed The Old Man and the Sea (1958), another sea-faring adventure, starring Spencer Tracy. They then offered the job to Dick Richards (Farewell, My Lovely) who was dropped from the project after he kept referring to the shark as a whale. Spielberg, who wanted the job desperately, convinced the producers in a meeting that he was the right man. He was hired in June 1973, before the release of The Sugarland Express.

Pre-Production

The script for Jaws underwent multiple revisions. Benchley wrote early drafts, but Carl Gottlieb, Spielberg’s friend, was brought in to add depth to the characters. Gottlieb, primarily known for writing comedy (All in the Family, The Odd Couple), was key in giving the core three characters (Quint, Chief Brody, and Hooper) depth through comedy. The final version of the script emphasized character development and pacing, while removing elements from the book (and Benchley’s initial script) that Spielberg and Universal felt might not translate well to film.

Spielberg’s shift away from the melodrama and sensationalism of Benchley’s book would prove to be a critical decision. This pivot away from the disaster aspect and towards developing real and believable characters would change the blockbuster genre forever. Gone were the mafia and romantic subplots in Benchley’s book and script, and added were more interactions between Brody and his family and the bonding of Brody, Hooper, and Quint.

Spielberg and production designer Joe Alves scouted numerous shooting locations for Jaws, eventually settling on Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts. The island had shallow waters that were far from the coast, thus giving the illusion of open sea while being manageable for the cast and crew. However, the decision to shoot on the ocean, as opposed to a tank or in a studio, was something unprecedented at the time and highly ambitious. The budget for Jaws was starting to spiral, and filming hadn’t even started yet.

Casting

Spielberg was more concerned with chemistry and authenticity than big-name stars when it came to his cast. The director knew that realism would make the terror all the more effective to the viewing audience. Spielberg also wanted to make sure that his actors blended in with the small-town aesthetic and feel of Martha’s Vineyard. To help achieve this, Spielberg cast Lorraine Gary (Ellen Brody) and Murray Hamilton (Mayor Vaughn) in critical supporting roles.

The role of Brody (Roy Scheider) was originally offered to Robert Duvall. However, Duvall was interested only in playing Quint. Charlton Heston also expressed a desire to play Brody, but Spielberg felt that Heston was too big to play the part of a small-town police chief. Scheider heard Spielberg talking about the film at a party and became intrigued. The director was hesitant as he didn’t want another ‘tough guy’ performance from Scheider ala The French Connection. The director soon relented, and Scheider was cast.

With filming on Jaws nine days away, the roles of Quint and Hooper had still not been cast. Spielberg initially wanted Jon Voight for Hooper and also considered casting Timothy Bottoms, Jan-Michael Vincent, Joel Grey, and Jeff Bridges. Ultimately, Spielberg selected Richard Dreyfuss for the part. Dreyfuss had made an impression on the director with his performance in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz. Spielberg has referred to Hooper as his alter ego.

The most difficult casting decision was that of Quint, the hardened shark hunter. The role was offered to several actors, including Lee Marvin and Sterling Hayden, both of whom declined. Classically trained actor and playwright Robert Shaw was eventually cast. This was despite reservations that Spielberg had about Shaw’s drinking habits and reputation for being difficult. The oil and vinegar chemistry between Shaw and Dreyfuss is undeniably electric.

Filming

Principal photography on Jaws began in May 1974 and was expected to last only fifty-five days. However, the long and troubled shoot ultimately extended to 159 days. Filming on a salt-filled ocean proved to be extremely challenging. Weather conditions, logistical setbacks, and the frequent failure of the mechanical shark nicknamed “Bruce” added stress and unpredictability to the process.

Spielberg and his team were forced to adapt creatively, leading to one of the film’s signature elements: the decision to suggest the shark’s presence rather than show it directly. Spielberg spoke to Vanity Fair in 2023 about the challenges of filming on the Atlantic Ocean:

“Jaws was my second movie, and I had a gut feeling about how to tell the story…But I had no idea, nor did anybody on the production, how difficult it was going to be to float that monstrosity and get it to work in the ocean… None of us understood the water…I never anticipated what was about to happen to us, and it wasn’t just because the shark wasn’t working. It was because deciding to go into the Atlantic to make a movie about a great white shark was insane. I didn’t see the insanity of it. I saw the authenticity of it”

The actors and crew endured seasickness, sunburn, and long hours waiting for the weather or light to improve. Yet, despite this, some of the film’s most iconic sequences were created during this period. Spielberg, editor Verna Fields, and cinematographer Bill Butler improvised techniques to maintain suspense without showing the often-inoperative shark. The now-famous use of point-of-view shots, floating barrels, and reaction-driven scares all came from necessity. Less truly became more, and the minimalist portrayal of the shark only heightened the tension.

As predicted, Shaw’s hard drinking and competitive nature played a big role in the film’s production as well as its brilliance. Shaw had a volatile relationship with Dreyfuss, and there was genuine tension that Spielberg stated benefited the film.

Shaw’s drinking also became a serious problem. During the filming of the Indianapolis monologue—a crucial scene in which Quint recounts the harrowing true story of the USS Indianapolis—Shaw delivered a drunken, unusable version. Embarrassed, he approached Spielberg the next day and asked to do it again sober. The result was a masterful take that remains one of the most memorable scenes in film history.

Post-Production

Spielberg made a quiet but consequential exit from the set. Due to the mounting stress and friction with some members of the cast and crew, Spielberg chose not to be present for the final filmed scene in which Brody and Hooper paddle back to shore. Spielberg feared a prank or ceremonial dunking as well as the need to distance himself emotionally from what had become a deeply taxing production. Assistant director Joe Alves oversaw the final day of filming.

John Williams, who had previously collaborated with Spielberg on The Sugarland Express, reteamed with the director for Jaws. The result was one of the most iconic film scores in history. Using just two alternating notes to mimic the sound of a lurking predator, Williams crafted a theme that immediately signaled impending doom.

Spielberg initially thought the score was a joke until he realized the power of its simplicity and its ability to provoke anxiety and anticipation. Williams’ music didn’t just accompany the film—it became an emotional character in its own right.

Editor Verna Fields played an essential role in shaping the final product. Her work helped turn disjointed and problematic footage into a coherent and suspenseful narrative. Her editing choices, such as cutting on reactions and using negative space to suggest danger, contributed immensely to the psychological impact of the film.

The final edit benefited from the synthesis of Fields’ pacing, Williams’ score, and Spielberg’s intuitive sense for suspense. Together, they created a rhythm that drew audiences in and kept them on edge throughout. The result was a film that felt polished and terrifying, despite its turbulent production history.

Release and Reception

Jaws premiered on June 20, 1975, and quickly became a cultural phenomenon. It was released in hundreds of theaters nationwide with a massive marketing campaign—a groundbreaking strategy at the time. The film shattered box office records, becoming the highest-grossing movie in history until the release of Star Wars in 1977.

Critics praised Jaws for its direction, performances, as well as its ability to evoke suspense, while pulling audiences back for multiple viewings. The film’s success ushered in the era of the summer blockbuster. At the 48th Academy Awards, Jaws received four Oscar nominations, winning three: Best Film Editing (Verna Fields), Best Original Score (John Williams), and Best Sound. The film was also nominated for Best Picture, although Spielberg was famously snubbed in the Best Director category.

The success of Jaws vaulted Spielberg into the ranks of Hollywood’s A-list directors and gave him the freedom to pursue ambitious projects. No longer a promising up-and-comer, Spielberg became a proven force in the industry. It laid the foundation for a career that would include some of the most beloved and influential films in cinematic history.

Legacy

Fifty years later, Jaws remains a landmark in American cinema. It established a new model for studio releases and redefined how thrillers could be structured. Its influence is evident in countless films that followed. While it inspired several sequels and countless imitators, the original stands alone for its craftsmanship and cultural impact. Spielberg’s direction, the strong performances, and the film’s innovative use of suspense continue to captivate viewers.

More than a movie about a shark, Jaws is a story of fear, survival, and the unyielding challenges of filmmaking. It is a cinematic achievement whose legacy continues to ripple through film history. It also did the impossible: it made people afraid of open water, public beaches, and in some cases…even their bathtubs.