Introduction

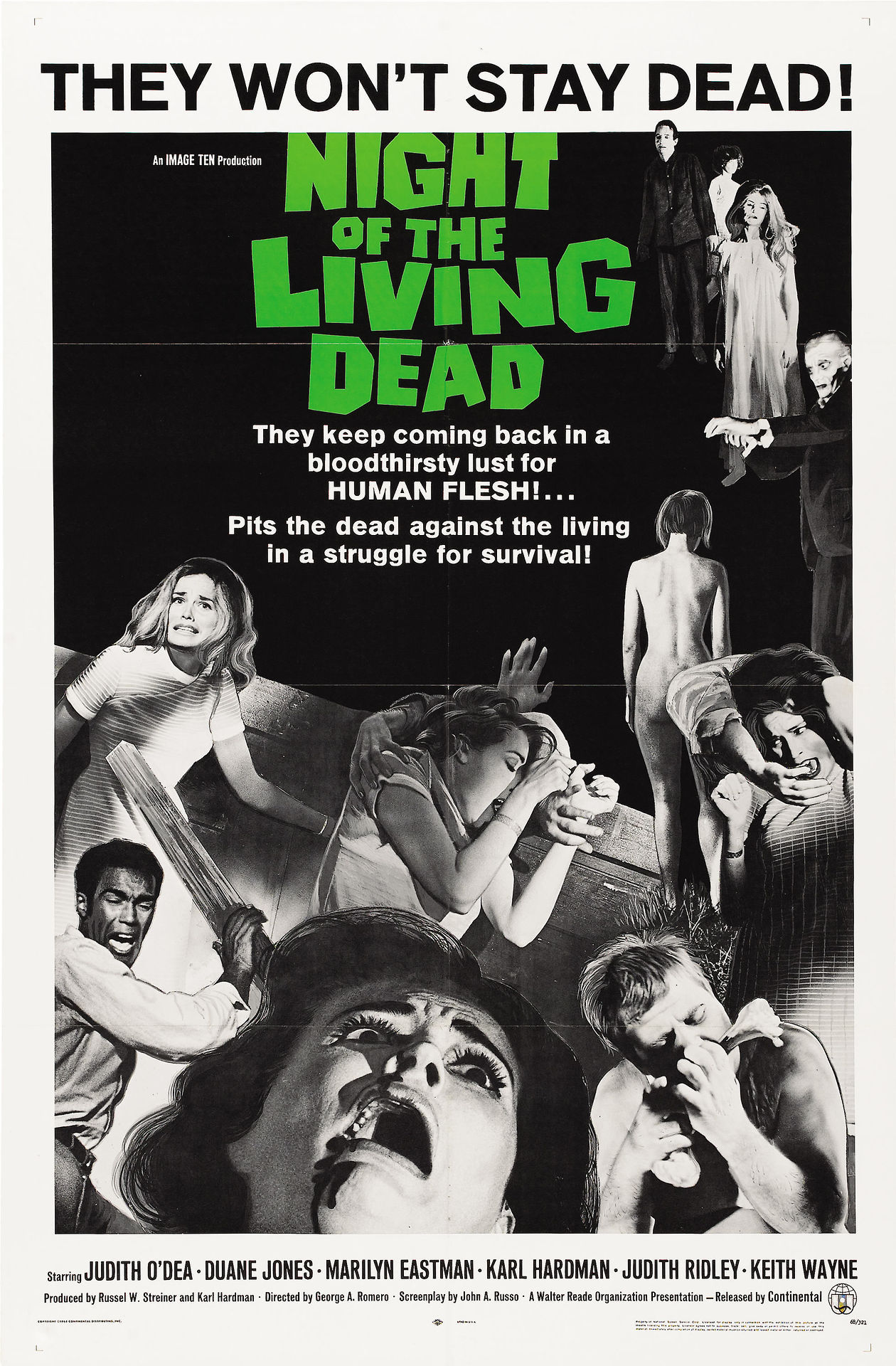

It’s hard to believe that Night of the Living Dead (1968) was made over fifty years ago. Zombie films have become so prevalent in the intervening decades that there seems to be no end to them. You might even say the entire concept has been (b)eaten to death.

Just off the top of our (exploding) heads, we have Dawn of the Dead (plus the “re-imagining of same), Day of the Dead, Land of the Dead, Diary of the Dead, Survival of the Dead, 28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later, Return of the Living Dead (parts 1 through 4), Resident Evil (and it’s multiple sequels), The Evil Dead, (and another 2 sequels and a remake), Zombieland, Shaun of the Dead, Fido, Zombie (with the tagline: “If you loved Dawn of the Dead, you’ll eat up Zombie”), Re-animator, Bride of Re-animator, Warning Sign, Quarantine, Night of the Creeps, Demons, Dead-Alive, World War Z, Last Train to Busan…

There are literally hundreds of them, and to drive home the point of how pervasive the trend is, how many Westerns, musicals, or other traditionally themed films can you quickly name from the past 50 years? Can you even come up with several hundred?

Zombie films have become a genre unto themselves. Night of the Living Dead was where it all began. It was the first film to invent the zombie “rules” we all know and love. Which are… you can only kill a zombie with a blow to the head. If bitten by a zombie, you’ll become infected, die, and in no time be walking around yourself. Zombies only like to eat living people. Zombies have poor motor skills, aren’t exactly articulate, and don’t have expansive vocabularies, etc.

Impact on the Landscape

While zombie films are (mind-blowing) fun, it’s also important to realize the huge impact that Night of the Living Dead had on the cultural landscape. It single-handedly stood the horror film on its head and sent it spinning off in a totally new direction. With its nihilistic approach, depiction of previously taboo subjects, and lack of a conventional happy ending, it marked a major turning point in the evolution of scary films. It’s no exaggeration to say that without it, we never would have had Jason, Freddy, Michael, Leatherface, Jigsaw, or the dozens of other movies that rely on gore and an overriding sense of doom to deliver a pervasive feeling of terror.

If you grew up watching any of these later movies, you can be forgiven for not appreciating how truly ground-breaking film Night of the Living Dead was. Shot in black and white on a shoestring budget, it didn’t bother with explanations, subplots, or moral judgments. The characters were simply thrown into a horrible situation in which things kept going from bad to worse.

The documentary-style nature of the film merely added to the feeling of unease it generated in moviegoers. More recent films may have upped the “gore” quotient. However, Night of the Living Dead has a raw, primal feel to it that has rarely been equaled. Watching it in the late 60s and early 70s, without the benefit of being “desensitized” to modern on-screen violence, was like living through an actual nightmare.

Background

So how did this extraordinary film come to be? Well, for starters, its creators were located nowhere near Hollywood. They lived in Pittsburgh, PA. There, in the mid-1960s, several of them worked for a local film production company called The Latent Image. They produced low-grade commercials and industrial films for a fledgling market in southwestern Pennsylvania. Some of the typical titles they turned out included gems like The Calgon Story, and Heinz Pickle No. 1.

One day, as told by John Russo in the Night of the Living Dead Film Book, a group of employees from Latent Image were hanging out at a local bar. They began discussing their life-long dreams of making it big in Hollywood. The discussion group included George Romero, John Russo, and Russell Streiner. All want to be big-time Hollywood movie-makers. Yet, they were smart enough to realize that career path was fraught with dead-ends. However, in talking, they realized that their years of experience with industrial projects had given them the technical know-how they needed to make a feature film.

They reached out to a production unit in town called Hardman Associates and recruited the President and Vice President, Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman. All told, they got ten people who each chipped in $600 to make a movie. With an operating budget of $6,000, they called their fledgling production company Image Ten, after the number of original investors. It was decided that Russo would write the movie, Romero would direct it, and Streiner, Hardman, and Eastman would produce and star in it.

Knowing that cost was going to be their biggest constraint, they worked hard to come up with a script that would break normal conventions, yet require minimal production values. After several months of wrangling, and in between their day jobs, Romero and Russo co-wrote a basic story that went for the jugular. It featured scenes of cannibalism, matricide, and over-the-top violence.

Soon the group realized that a measly $6,000 wasn’t going to be nearly enough to get their production off the ground. They then proceeded to find another ten investors, doubling their budget to $12,000. Eventually, those funds escalated to $60,000 when they actually began filming. Still, an unbelievably small stake for any film, even in 1967.

The production was located about forty miles north of Pittsburgh, near a town called Evans City. They had to act fast. That part of Pennsylvania usually saw an early autumn, and by the time they began shooting, it was already July. At the time, the Image Ten team didn’t even have a title for the film yet. They merely referred to it as “The Monster Flick.” Even by today’s standards, the film’s plot stands out for its sparseness and originality.

Synopsis

Night of the Living Dead opens with Barbara (Judith O’Dea) and her brother Johnny (Russell Streiner) visiting a remote cemetery to lay a wreath on their father’s grave. Barbara finds the setting creepy, a fact that Johnny uses as an excuse to tease her by telling her in his best Boris Karloff imitation: “…they’re coming to get you, Barbara…” Among the gravestones, a lone man is walking awkwardly and approaches the couple. And Then, for no apparent reason, he suddenly attacks Barbara. Johnny tries to defend her, but the man wrestles him to the ground, where Johnny hits his head against a gravestone.

The man chases Barbara to a local farmhouse, where she is soon joined by another man named Ben. Ben tells her that there’s something happening across the countryside and that they need to board up the house to protect themselves. They turn on the radio to hear news reports about instances of mass homicides. Meanwhile, more and more shuffling individuals begin to gather outside the home.

Soon, Ben and Barbara learn they are not alone. Hiding in the cellar are Helen (Marilyn Eastman) and Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman). They have a young daughter who has been bitten by one of the “ghouls” and is very ill. Also in the cellar are a young couple named Tom and Judy. Harry turns out to be a very opinionated and obnoxious individual who urges the group to barricade themselves in the cellar behind a heavy door. Ben emerges as the leader of the group and argues that they have a better chance if they stay upstairs. That way, if one of the “things” breaks in, they’ll have somewhere to run. Ben and Harry argue violently over their respective positions.

A television set is found. From local emergency news broadcasts, they learn about the mass murders taking place throughout the area. Incredibly, the perpetrators appear to be the freshly dead, who seem to have developed a taste for human flesh and are “devouring” their victims. The newscasts tell of “rescue” centers and urge people to try to make their way there in order to find assistance.

The group hatch a plan. They find keys to a nearby truck and plan to drive it to a pump out back in order to refuel it. But the plan goes horribly wrong when they inadvertently spill gasoline on the vehicle. Tom and Judy are killed when the truck catches fire and explodes. Inside the house, the rest of the group is horrified to see the ghouls eating the remains of the couple.

The house loses electricity, and this is the cue for the dead to begin their final assault. After a struggle, Harry is fatally shot by Ben and stumbles back to the basement. His daughter has just died and begins to eat him. Harry’s wife also runs downstairs and is dispatched by the young girl using a garden trowel. Meanwhile, up above, the dead have gotten into the house. Johnny, now a ghoul, grabs Barbara and drags her outside to her fate. This leaves Ben alone. He runs into the cellar and boards up the door. He uses a shotgun to shoot Harry and Helen, both of whom have come back to life.

The next morning, the sun comes up. Ben thinks he hears something. Carefully, he takes the boards off the door and peeks out. In the yard is a local posse who has been going through the countryside shooting ghouls and rescuing individuals. Seeing Ben peering through a window, they mistake him for one of the living dead and kill him with a single shot. “That’s another one for the fire…” the posse leader yells out. The men drag Ben’s body and throw it onto a giant bonfire. No one survives.

Trivia

For those of you already familiar with the movie, here’s some related trivia you may find interesting:

- The filmmakers couldn’t afford original music. So, the distinctive score was created from a stock music library. You can also hear some of the same tracks in other schlocky sci-fi films from the 1950s. Including The Hideous Sun Demon and Teenagers From Outer Space.

- One of the lighting technicians in the film was Joe Unitas, cousin of football legend Johnny Unitas. They offered Joe a percentage of the profits. But, thinking the film wasn’t going anywhere, he opted for a straight fee and lost out on a lot of money.

- The film never mentions the word “zombie.” Not even once. Instead, the walking dead are referred to as “ghouls.”

- During the montage in which Ben boards up the house, you can spot a Lowell light stand that was inadvertently left in the frame. It’s a standard issue for most industrial lighting kits.

- When Barbara first enters the house, she encounters a corpse at the top of the stairs. The head bust was created by George Romero out of a hobby shop kit entitled “The Living Skull.” Kids all over the country used it for various science fair projects.

- The car that Barbara drives into the tree belongs to producer Russell Streiner’s mother. It had recently been in an auto accident. So, they saved some money by making it look as if the tree had scraped the side of the car…when the damage had been there all along.

- The ghoul who eats the bug off the tree is played by Marilyn Eastman. The same woman who starred as Helen. She’s nearly unrecognizable under all the makeup. Writer John Russo also plays the zombie who gets dispatched early on with a tire iron to the forehead. Just another example of how filmmakers cut corners to save money.

- One of the investors in the film owned a meatpacking plant. He generously donated all the animal organs and innards used in the cannibal scenes. (Without that bit of luck, there’s no telling what they would have done).

- The roving reporter in the news footage shown on the television was played by “Chilly Billy Cardille.” He hosted a popular horror movie show on Saturday nights in Pittsburgh.

- Notice you never see a bathroom in the house. That’s because it was so old, it didn’t have any running water.

Post-Production

After the film was finished, it was screened for all of the investors and interested family members. John Russo later remembered he knew they were onto something when his future wife almost broke his fingers by gripping his hand too tightly during the preview. The group thought they had an original product, and felt they had met the goals they had set out for themselves. But they were still having money problems. A local film production lab named WRS had agreed to extend them credit in order to do all the film-developing work. But without a distributor, Image Ten had no way to pay the lab back.

One afternoon, Russo, Romero, and Streiner were having beers at a bar with the owner of WRS. The bar just happened to have chess sets for the customers to play with. After having one too many, Streiner and the head of WRS began bragging about their prowess with the chess pieces. And soon enough, a bet was wagered.

If Streiner won, WRS would do all of the lab work for free. But if WRS came out ahead, they would owe double. For all practical purposes that would have meant the end of the movie. Because without a finished print, and with no financial means to bail it out, they’d have nothing to show. Several hours later, Streiner managed to pull out a victory. But not before Romero and Russo went through several heart attacks.

Finally, the team had a finished print in their hands. They even had a title for the movie: “Night of the Flesh Eaters.” And then it suddenly dawned on them how desperately they needed a distributor. Romero and Russo took a copy of the film to New York City and began shopping it to prospective buyers. Columbia Pictures showed some interest. As did American International Pictures. But both asked them to reshoot the ending to make it “happy.” The team refused. Despite the pressure to pay off their investors, Romero and Russo stuck to their guns.

Eventually, they got an offer from The Walter Reade Organization. They were strange bedfellows. Walter Reade was primarily noted for distributing European art films. They asked for some cuts to tighten up the film but said that they liked the ending and wanted to keep it intact.

However, they made one other request which would have enormous consequences. After a copyright search, they felt that the title was too similar to some other films. So, to play it safe, they asked that the movie be renamed Night of the Living Dead. No one had an issue with it, and a new title sequence was created. However, in doing so, the lab inadvertently removed the copyright notice from the master print. Which technically left the film without a trademark. Years later, when Walter Reade fell into bankruptcy, the film lost its copyright. As a result, it fell into the public domain.

Criticism

Despite the huge financial success the movie enjoyed (to say nothing of the home video market which emerged some 15 years later), Image Ten saw very little of the money. Anyone who wanted could obtain a copy of the film, put it on VHS, and sell it for whatever price they chose. The original “Night of the Living Dead” was shot on 35 mm film. The same as any feature-length Hollywood movie. But after all the prints, reprints, and slow-speed recordings, you were hard-pressed to find a decent version of it until the advent of DVD.

The movie regularly showed up at the bottom of most Walmart bargain bins or was packaged as part of various “terror collections” consisting of other public domain titles. To this day, you can download a copy for free at The Internet Archive. (However, if you want to see the film in its original glory for yourself, we recommend obtaining a remastered version on DVD).

But at the time, all this was years in the future. In the late 60s, “Night” landed like a bombshell. It was so totally unlike any previous film that the exhibition market didn’t know how to handle it. Most horror movies at the time were screened during the afternoon hours for younger audiences. Since this pre-dated the rating code by a year, many unsuspecting parents dropped off their kids to see the movie. With little concept of what awaited them.

Film critic Roger Ebert liked the film, but after attending a matinee wrote a scathing review for the Chicago Sun-Times. In it, he harshly criticized parents and theater owners who let children see the movie by themselves. It was later reprinted in Reader’s Digest:

“I felt real terror in that neighborhood theater. I don’t think the younger kids really knew what hit them. They were used to going to movies, sure, but this was something else… The kids in the audience were stunned. There was almost complete silence… There was a little girl across the aisle from me, maybe nine years old, who was sitting very still in her seat and crying. It’s hard to remember what sort of effect this movie might have had on you when you were six or seven… Nobody got out alive. It’s just over, that’s all.”

Of course, children weren’t the intended audience for “Night of the Living Dead.” Adults were. One might even say that the horror film reached a heightened sense of maturity with the release of the film. And very quickly word spread that something special and unique was on tap for those adults hungry and eager to take their movie-going experience to the next level. If ever a film became a hit because of word of mouth, this was it.

Legacy

“Night” was the first feature to kick off the midnight movie craze. For two years, the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village screened sold-out shows at 12 a.m. for eager audiences. The phenomenon quickly spread. Soon, other movies such as Pink Flamingos, El Topo, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Up in Smoke would become midnight movie staples for audiences yearning for a “different” form of entertainment.

But even more than that, “Night of the Living Dead” was the starter pistol for a new breed of horror film. Building on its undeniable success, other midnight 70’s movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Last House on the Left, and The Hills Have Eyes picked up on “Night’s” themes and motifs and ran with them.

Today, the film is considered a bona fide classic. It’s been part of multiple exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, and has been selected by the Library of Congress for inclusion in the National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically, [and] aesthetically significant.” In describing the film, critic Rex Reed once famously said:

“If you want to see what turns a B movie into a classic…don’t miss NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. It is unthinkable for anyone seriously interested in horror movies not to see it.”

This leaves us with one last point to ponder. One of the most intriguing things about “Night of the Living Dead” is the conflict between Harry and Ben. The former, if you remember, argued strenuously that ”the safest place is in the basement!” But Harry is a cowardly bully who only cares about himself. He’s more concerned with being right than doing the right thing.

Ben, on the other hand, is not only brave but seems genuinely concerned with the welfare of others. He takes the lead in getting them to stay upstairs and board up the house. Ben demonstrates genuine leadership traits and everyone in the audience sides with him. But, in the end, he turns out to be horribly wrong. And everyone in that house goes to their doom by following his lead. If only they had just stayed in the basement…

Conclusion

Upon reflection, it’s just another example of how chilling and subversive the film truly is. And ties in nicely with these final thoughts offered by Stuart M. Kaminsky in Cinefantastique:

“Death in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD is meaningless, total, inevitable…Romero’s film is a bleak, relentless nightmare of our fears in which nothing can save us, in which we are trapped between the horror of death and life…Sitting through NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD is like an extensive session with a good psychiatrist. You come to grips with things you would often rather not face, but having faced them, is somehow to lessen their ultimate horror.”

It’s difficult to think of a better way to describe what makes a good scare picture. And why over 50 years since it was first released, “Night of the Living Dead” still stands near the top of the heap as one of film history’s ultimate exercises in sheer terror.