Introduction

Freaks is today recognized as one of the most disturbing, bizarre, and unforgettable films ever made. The fact that it was produced way back in 1932 at the “classiest” Hollywood studio of the era is even more remarkable. Also, despite its age, it’s still highly regarded as an extremely important benchmark in the history of horror films.

The story behind the making of Freaks is fascinating all by itself. As is the background of its very unusual director, Tod Browning. Browning, before having his career brought to an abrupt end, was one of the silent cinema’s most celebrated creative talents.

Tod Browning

Tod Browning was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1880. He was the nephew of early baseball star Pete Browning, the original “Louisville Slugger.” Most kids dream of running away from home and joining the circus. at age 15, Tod Browning did just that. He learned to perform in various sideshows and even became a clown for Ringling Brothers.

While in New York, Browning met legendary early filmmaker D.W. Griffith and after moving to Hollywood, even got a job as an extra in the epic film Intolerance. He was bitten by the film bug and decided to abandon the circus in favor of this new art form. Browning acted in over fifty small films and got to direct another eleven on his own.

Even at the dawn of the film era, Hollywood had a lot to offer in the way of temptation. Browning pursued a wild lifestyle, partying and drinking until all hours of the night (and morning). Browning’s job as a director gave him access to many would-be starlets, and like many who followed in his footsteps, he began to act as if normal rules of conduct didn’t apply to him. It wasn’t at all unusual for Browning to go on wild benders for days at a time with a coterie of close friends.

Tragedy

However, in 1915, this lifestyle came to an abrupt end. Browning and two buddies were out late one night, drinking heavily and driving through the hills outside of Los Angeles. Browning was behind the wheel when he drove the car at full speed into a moving train. One of his friends was killed instantly, while the other suffered serious injuries.

The police report stipulated that some elements of the crash were too graphic to even put into writing. For his part, Browning was barely left alive with a shattered right leg, the loss of all his front teeth, and major internal injuries. Like his circus experiences, this accident would likewise play a major role in shaping his later life.

The Browning and Chaney Team

Browning was bedridden for the better part of two years. After recovering, he went back to work as a scriptwriter and film director. It was around this time that he was introduced to rising silent film star Lon Chaney (The Man of a Thousand Faces).

Each found they shared common interests and formed a creative partnership. Browning was fascinated with deformed characters who were considered outsiders to society, while Chaney specialized in devising horrific makeup. During the 1920s, the two would collaborate on ten separate films. All of them were extremely profitable.

Silent Success

Among these collaborations between Browning and Chaney was 1925’s The Unholy Three which featured a trio of hardened criminals: Chaney disguised as a kindly old lady, a midget who masquerades as a cigar-chomping baby, and a circus strongman who does the heavy lifting for the gang’s misdeeds.

Then, in 1927, there was The Unknown in which Chaney portrayed a serial killer who possesses double thumbs. It’s an abnormality he hides from the police by taking refuge in a circus and wearing a concealed straitjacket to create the illusion he doesn’t have any arms.

Toward the end of the silent era, Browning and Chaney made London After Midnight, which is today considered a “lost film.” Widely recognized as featuring one of the first “vampires” on screen, Chaney’s makeup was truly memorable. So memorable that at the time of the film’s release, a man was convicted of murdering a woman in London. His alibi? He claimed Chaney’s performance had driven him insane.

However, Browning’s fruitful collaboration with Chaney came to an abrupt end in 1930. After making his one and only “talkie” (a remake of “The Unholy Three“), Chaney was stricken with throat cancer and died. This left Browning despondent and looking for his next project.

Dracula

Over at Universal Studios, there was a hot property based on an extremely successful stage play of the time. It featured a Transylvanian Count with an appetite for human blood. Originally, Universal had acquired the rights to Dracula intending to get Chaney to play the lead. However now, all Universal was left with was Chaney’s long-standing director. So, they offered Browning the job.

By most accounts, the production of Dracula was a complete mess. Browning seemed to have no interest in the project whatsoever and began to drink heavily on the set. Feeling out of his element on a “talking picture” and without Chaney to collaborate with, he became listless, uninvolved, and sometimes just outright too drunk to provide any input whatsoever on certain key scenes.

Freund Takes Over

Under these conditions, cameraman Karl Freund stepped up to take over many of the directorial duties. Freund was an expert at expressionist lighting and had previously worked in Germany on such classics as Metropolis. He, more than anyone, was responsible for creating the look of Dracula. Between Freund’s extraordinary cinematography and Bela Lugosi’s definitive interpretation of the Count, Universal had a huge hit on their hands. Later that year, the studio followed up with James Whale’s Frankenstein.

These two films were among the biggest draws of the early sound era and suddenly elevated Universal from “minor” status to a major player in the Hollywood hierarchy. Also, Browning’s stock had risen to unheard-of heights. Little was known about his actual behavior on the set of Dracula.

MGM Calls

Over at MGM, production head Irving Thalberg looked at Universal’s record profits and did some calculations of his own. He tasked his team of producers with the development of the studio’s slate of scary films. He told them:

“What I want is the ultimate in horror”

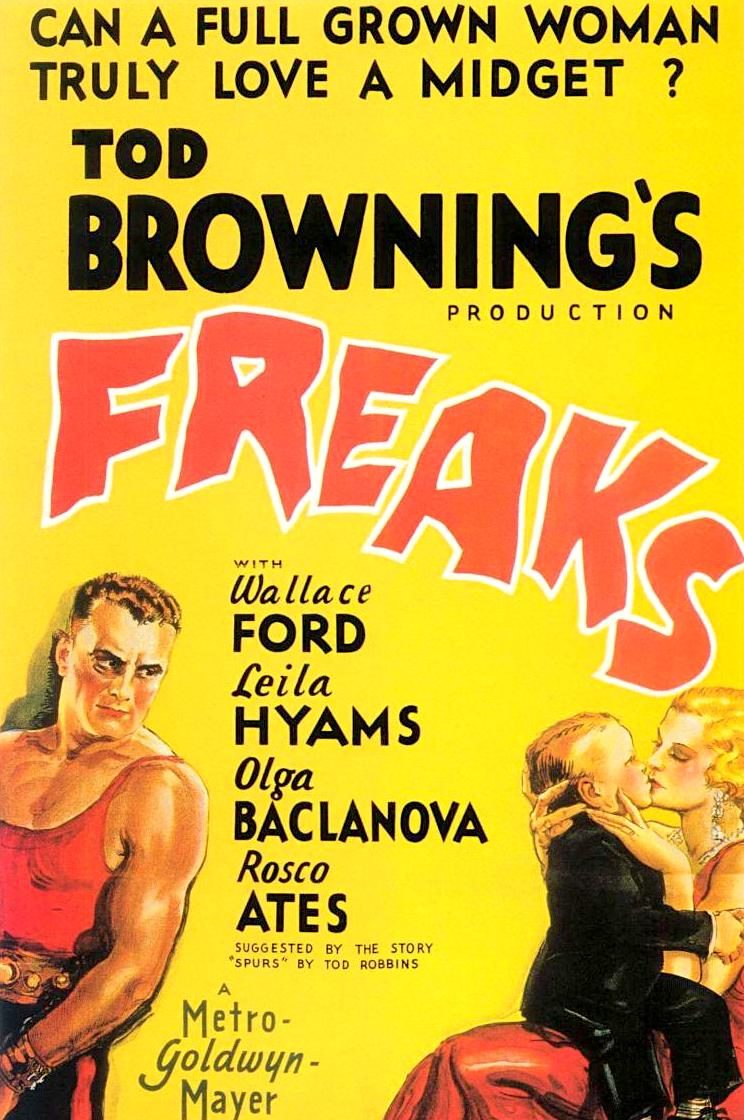

Urged on by their boss, MGM’s production team approached Browning and asked him to sign a contract with their studio. They also asked him if he had any properties he would like to direct. Browning gave them a short story called “Spurs,” written by Tod Robbins.

When the producers met with Thalberg, they showed him a script of the film that Browning wanted to make. A look of revulsion came over Thalberg’s face, and he reportedly put his head in his hands and replied with an air of resignation:

“Well, I asked for horror. And yes, it’s just horrible”

Then, to everyone’s complete amazement, he gave the go-ahead and green-lit the production. The year was 1932 and the table was set for what is widely considered to be the most bizarre and controversial film to ever come out of the Hollywood studio system. Before or since.

Browning’s Unusual Film

Browning’s experiences in the circus gave him an appreciation for those who were “different” and not part of mainstream society. The director wanted to make a lurid melodrama set in this unique environment. One that would feature the ultimate outcasts: sideshow attractions. Specifically, the deformed, the disabled, and the bizarre. Only for this particular production, he wasn’t going to soft-pedal anything or use “regular” actors. He wanted to use real-life circus performers. The name of his film was going to be called Freaks.

With the resources of Hollywood’s largest movie studio at his disposal, Browning dispatched talent scouts throughout the country to hire the most unusual human oddities they could find. Siamese twins, armless and legless performers, a human skeleton, a bearded lady, midgets, dwarfs, pinheads. These were just some of the people who were given an all-expenses-paid trip to Hollywood.

Of course, the real “monsters” in the movie aren’t the freaks at all. They’re the “normal people” who are self-serving and murderous villains. In contrast, Browning goes out of his way to show that the physically deformed are just like us. He shows them leading normal lives, with a sense of humor, and dignity to match.

Not Your Typical Studio Production

As you might imagine, the production of this film was anything but normal. MGM was at that time known as the home of the Hollywood “elite.” The stars of Freaks would eat lunch every day with everyone else in the studio commissary, including other MGM stars such as Greta Garbo and John Barrymore.

Imagine what it must have been like for the performers in the film. They were plucked on short notice from desperate circumstances, or a sideshow existence. For these performers, it must have seemed like a dream.

Unfortunately, other members of the MGM family were not amused. Author F. Scott Fitzgerald was on contract as a scriptwriter to the studio at the same time Freaks was being filmed. One day at lunch, while nursing a hangover, he observed two Siamese sisters ordering off of the same menu. He ran outside to throw up. Other members of the studio began to complain up the chain.

Complaints Up the Chain

Some of these complaints reached the ear of Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM. In addition to the lunchroom issues, some mid-level executives began to ask out loud if Freaks was the kind of production the studio wanted to be associated with. Mayer had reservations and issues of his own with Irving Thalberg, who had initiated the project. But he backed the production, stating:

“Tod Browning is a great director…And I’m going to let him make his movie”

Mayer may have had second thoughts after the film was finally shown to a preview audience. To say that it wasn’t well-received would be an understatement. As one MGM producer recalled:

“They didn’t just walk out of the theater in the middle of the screening. They RAN”

Horrific Content

Making use of a framing device, Freaks opens with a carnival “barker” giving patrons a tour of various circus sideshow attractions. At one point, the group comes to a barricaded enclosure. When the group looks down into the pen, the men recoil in disgust, while one of the women screams in horror and begins sobbing. The barker later explains:

“No one knows how she got this way…some say it was the code of the freaks”

And with that, the camera cuts to the inside of the enclosure. There, we are witness to a truly horrifying sight. It’s one of the “human” stars of the film who has been transformed into a grotesque human and chicken hybrid. With her arms amputated, her eye gouged out, and her entire bottom half covered in feathers, all she can do is squawk incoherently.

Nearly ninety years later, it’s still widely considered to be a supremely shocking moment. That, along with other imagery in the film, retains the power to induce shudders. One can only imagine the reaction from audiences at the time.

Release and Reaction

Alarmed, MGM took control of the film away from Browning and cut out nearly a third of it. After re-titling it for some markets (calling it Nature’s Mistakes), they stuck on a prologue and “happy ending” which was completely out of sync with the rest of the film. MGM then held its collective breath and gave the picture a general release.

You can guess what happened next. Despite having had many objectionable scenes cut out, the film was positively crucified. Local censor boards tried to ban it. The Federation of Women and dozens of other groups organized protests against it.

One woman sued MGM, claiming Freaks caused her to have a miscarriage. The critics hated it. Words like “exploitative,” “sickening,” and “irredeemable” were the consensus at the time. Browning’s plea for understanding and tolerance was lost amid all the yelling and shouting. The sight of actual physical deformities being shown on screen was too much for audiences of the time to bear. Indeed, the film was banned outright in Great Britain for the next thirty years.

MGM had a bona fide public relations disaster on its hands. In addition to the film’s instant notoriety, it also lost a lot of money. After just a few short weeks, they pulled Freaks from distribution and stuck it away in their vaults.

Reappraisal

There it sat until the mid-1960s. As tastes changed, and the study of cinema became more mainstream, people began to remember this strange little film that only had a short run in theaters way back in 1932. Some people began to seek it out to see what the fuss was all about. Before long, the movie had become a staple at film festivals and midnight showings on college campuses all around the country.

The counterculture, which thrived during this later decade, grasped the message that Browning was trying to convey. Namely that “normalcy” and “conformity” were relative terms. Freaks was hailed as a groundbreaking film and is today considered a milestone in horror cinema.

A Career in Decline

Browning never got to enjoy the film’s renaissance as Freaks effectively ended his career. MGM still had him under contract, but he had quite simply become an embarrassment to the studio. They struggled to find suitable and “safe” material for him to direct. Browning was never again allowed to have creative freedom in any subsequent production. Out of the handful of films he made after “Freaks,” only two are noteworthy.

The first was Mark of the Vampire. It was an out-and-out remake of London After Midnight but this time with Bela Lugosi playing a vampire who haunts a huge mansion. At the end of the film, you find out that Lugosi was never really a vampire at all, but is just an actor playing a role. It’s an example of just how far MGM was willing to go to avoid anything even remotely objectionable when it came to Browning.

Excellent photography was also the hallmark of Browning’s last major film, The Devil Doll. Released in 1936, it tells the story of a “mad scientist” who creates miniature people to do his bidding. For its time, the film has amazing visual effects but also suffered from what by now must seem like an old theme: an anti-climatic “happy” ending that seems totally out of place with the rest of the picture. It was mandated by MGM as part of their effort to keep Browning in check.

Outcast and Reclusion

The same year that The Devil Doll was released, MGM’s production chief Irving Thalberg died. He had known Browning since his silent movie days and was his only ally at the studio. Five years after being on top of the world with the release of Dracula, Browning was unceremoniously thrown out of his workplace and forced to retire from the film industry.

For the next 25 years, Browning continued to battle alcoholism and lived the life of a recluse. Eventually, he was able to give up hard liquor but remained fond of beer until he died. He consistently refused to give interviews of any sort and never spoke publicly about his colorful life experiences.

When a few people did manage to get close to him, Browning would disown their friendship as soon as the subject of his Hollywood past came up. Indeed, his bitterness toward the movie industry was palpable. According to friends, he spent nearly every night staying up late and watching old movies on television. Consequently, even his own family rarely saw him.

A Final Goodbye

Browning died in 1962. According to his final wishes, there was no funeral or ceremony of any sort but his will did contain one unusual request. While his body rested at the local funeral home before burial, Browning had asked for one of his old drinking buddies from years gone by to stop in for a solitary visit. He wanted his friend to bring one last case of Coors beer and share it with him beside the casket.

One night, the request was granted, and after several hours, the man quietly left. The owners of the funeral home never even asked him his name. Browning was subsequently laid to rest in the Rosedale Ceremony in Los Angeles, but not before having earned a prominent place for himself in one of cinema history’s darkest corners.